Since 1934, Gordon and Margaret had lived for several years in the end

house in Edward Street. The dwellings had been condemned years earlier

as being too damp and dilapidated for human habitation but moving there

had been the first step of what is now called 'upward mobility'. Their

first hovel, where Michael had been born, was in St. Thomas's Place.

It had been much worse, with water running down the walls, and there

was only one bedroom. Michael liked Edward Street, especially now he had his friend, Rob.

They saw each other twice a week at Michael's.

Sometimes, Margaret went up to Williamson's Park, if the weather was good. The

two boys played great adventure games there, exploring its fifty-four

acres more and more widely, finding some of the secret places.

They had an ice-cream or a drink of fizzy pop after they'd finished

their adventures. The mothers sat chatting on their usual seat. The

two boys stayed apart on the grass. Rob said, "I think my Dad might

be going to be a soldier."

"How do you know?"

"I heard him telling my Mam somebody had to stop the bugger. He said

that he needed shooting and he was the man to do it."

Michael took another lick at his ice-cream then asked, "What's a bugger?"

"I think it's another name for a Franco."

Michael wondered why they never went into Rob's house. One day, when

he was playing under the table, he heard his Mam say to his Dad, "It

was pouring down today. We got caught in a really heavy shower but she

couldn't let us in the house. Her husband won't have anybody indoors.

I expect he has his reasons. It takes all kinds I suppose."

"Perhaps they haven't got a lot," said Gordon, "and they don't want

you to see."

"I don't know about that," replied Margaret. "it's a great big posh

house."

Margaret came from a very large gregarious family. Her mother

had always welcomed people indoors.

Michael wondered what Rob's dad was like. Rob never said much about

him or any of his family. He didn't speak about grandparents or aunts

and uncles.

Michael had lots of relatives. Three of his father's aunts lived in

Edward Street. They let him go in all of their houses. He liked going

to Aunt Elsie's best.

All three were Nan's sisters-in-law. Like Nan, they were all war widows.

Their husbands had died with Granddad Eli in France, in 1915 -- and they weren't

the only war widows in Lancaster, by a long shot. Lots of that generation

of women wore black, mourning their lost men for the rest of their lives.

There were long columns of names on Lancaster War Memorial, in a little

garden at the side of the Ashton Hall. One day, on their way to go and

see Nan, Michael's Mam took him and pointed out the name of his Granddad

Eli.

Despite their common tragedy, the three sisters had not bonded with

little, fiery, red-headed Nan. They thought her bossy and a bit snooty.

Elsie said, "I don't know who she thinks she is. She's no better than

us."

Margaret agreed, "I've tried but she's not easy to get on with."

Michael used to hear all sorts of things that grown-ups said, while

he was playing on the floor with his soldiers or looking at his picture

books. He liked it on the floor, on the cool lino. He was fascinated

by the patterns which his Dad had helped to make at work. There were

brown and beige variegated rectangles, all exactly the same size, fitting

together like a perfect jig-saw puzzle.

The aunts were close allies with each other in adversity, including

being against Nan, but they were not always in-and-out of each other's

houses like some. It was only Aunt Elsie of the three who kept open-house

and Margaret and Michael liked her the best.

"Hello love, Hello Michael. Sit yourselves down! I'm glad you've called

in. I'll just put the kettle on. And we'll have a nice little chat.

You have got a few minutes to spare love?"

Margaret always had time to spare. She'd have been disappointed if she

hadn't been asked to stay.

Aunt Elsie was different from the other two aunts in lots of ways. For

a start she'd married again, after the war. She had two children by

her dead, soldier husband and two by Jim, her second. Jim drove one

of the chocolate-and-cream coloured Lancaster buses.

Elsie's youngest child, Joan, was like a big sister to Michael. She

was five years older than he was. When he was a baby, she liked to rock

his pram, play with him on the rug in front of the fire, helped teach

him to crawl, then to walk. Her patience was inexhaustible. She was

a tall child with the red hair and greenish eyes which several of her

family had. In her view, Michael could do no wrong. After Gwyn was born,

she stayed faithful to Michael. She made a fuss of the new baby but

Michael always came first.

Michael loved Joan's pretty, friendly gaze on him. He liked to watch

her when she did things he could not do, like skipping, doing forward-rolls,

keeping a spinning top going with a whip, turning the mangle handle

without help, fetching the bucket filled with coal from the cellar.

She was always calling at Margaret's, when she was not at school, and

Margaret loved to see her.

Joan's mother, Aunt Elsie, had longish, lank, black hair, streaked with

grey. She had grey eyes and pale cheeks. She dressed in black, wore

a slack, formless frock , low-heeled shoes, woollen shawl, thick stockings.

She was lame and carried a walking stick with her, or leaned on it when

she was seated. She was friendly but rarely went out. Her world normally

came to her. The older children, who still lived at home, did the shopping

and most of the housework for her. She had a rocking-chair and spent

most of her time sitting in it, warming herself by the fire and listening

to her wireless.

She asked Margaret what she thought about the King abdicating. Margaret

came from Wales where Edward had curried favour with the miners.

"I think it's a shame. They should have let him marry that woman he

loves. He'd have made a good king."

"Blooming Fascist, that's what I think he is. Him and her! That woman

of his, scrawny bitch, more like a fellah! She's worse than him. Both

of them, always sucking round that Hitler. Wouldn't trust that pair

as far as I can see them!"

"Oh!" replied Margaret. It was all beyond her.

Aunt Elsie was modern in her outlook. She was one of the first in the

street to have a wireless and she read a lot, including the Daily

Herald, a Labour Party newspaper, every day.

There had been a hefty insurance when her first husband was killed.

She bought the house she lived in and was always trying to fight a losing

battle against the jerry-built damp abode. That was how she'd damaged

her leg, doing a bit of plastering all by herself.

She'd slipped off the step-ladder and badly-twisted her knee.

Although her buying of the property had been somewhat ill-advised she

still kept on at Margaret to buy a house.

"Move heaven and earth and move out of that place you're in or you'll

lose your little'un! She'll get pneumonia. Save every penny you can

love, and buy a place of your own! Move to one of the nice new estates!"

Michael wished people would not be for ever talking about moving. He

loved it where he was.

Joan had told him that soon, the Corporation were going to turn the

empty site, straight across from his house, into a children's playground.

There would be a high slide and a roundabout to play on. Joan said boys

and girls would come from all of the other streets nearby to play there

and he'd meet lots of new friends.

"I'll take you over there," she promised. "It'll be really good. You

and Rob will have it all to yourselves when the other children are at

school."

"Will you let me go there, Mam?" asked Michael. You never could tell

with his mother, what she might decide.

"I expect so love, but only if Joan takes you. It'll be alright if Joan

is there to look after you."

"Told you so, didn't I? " laughed Joan. She was really good was Joan. She was always making things happen for him.

Web Links

• Lancaster War Memorial is located in a small Garden of

Remembrance on the east side of the Town Hall. It was designed by

Thomas Mawson and Sons and now commemorates the

dead of both two world wars and other conflicts. 10 bronze panels

at the rear record the names of 1,010 Lancastrians who fell in the First

World War and were dedicated on 3rd December 1924. The

plinth in front of the statue carries the names of a further 300 who fell in

1939-45.

• Westfield War Memorial Village, which was buily in Lancaster in 1924, was initially created for ex-service men, women and families after World War I. The village is owned by registered

charity War Memorial Village Lancaster and is home to 189 ex-service

men, women and families. The homes are leased to Guinness Northern Counties.

Discover a marvellous trip back to Lancaster of the past by author Bill Jervis, which we plan to release in weekly segments. Although the story is set in Lancaster the family and most of the characters within are entirely fictitious -- but this story does chart a way of life largely lost and which many Lancastrians may recall with equal horror and affection...

Wednesday, 28 December 2011

Monday, 5 December 2011

Chapter Ten: Pranks

|

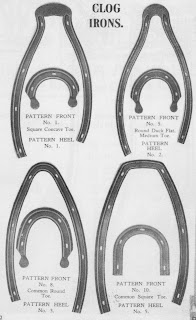

| Clog Irons |

Michael's and Rob's mothers became friends. Mrs Matthews would leave Rob at Michael's while she went shopping. Sometimes, Rob's mother would stay at Michael's and look after the four children, while Michael's mother went up-town.

Michael knew all about Robin Hood and King Arthur and the boys played pretend games and acted the stories. Michael had some lead soldiers which his Dad's mate at work had made for him. Only one soldier was in a coloured uniform. The others were just plain lead.

"Don't suck them! They're poisonous!" warned Michael, repeating what his Dad had told him.

When it was Michael's turn to have the painted one, he imagined it was his heroic Grandad Eli, the one he had never known, the one who had been killed in the war, in 1915. One day, Rob said, "There's going to be another war."

Michael responded with, "Who says so?"

"My dad. He says if we don't listen to Churchill, we'll be in big trouble."

"Who's Churchill?

"I don't know. I haven't asked him."

Another time, the two boys were playing out the front and a passing neighbour, Celia Wilkinson, gave them a bobbin with thread on it. Michael knew her friendly face well. She was one of the workers who waved to him when he was watching them all go to the mill on Moor Lane.

She'd nicked it from work, and Michael said, "Coo, it's got miles on it. Let's tie up the houses." So they did.

It was quiet in the street, a mild, spring afternoon, and nobody about. They tied the end of the thread to Michael's front-door knocker and unravelled it carefully down the side alley. They turned left down the back alley, under the shadow of the throbbing mill, and went back into Edward Street from the far-side, near the little shop, which was closed for the afternoon.

Finally, they made their way back up the street, keeping the thread taut across windowsills and across doorways as they went.

They did not snap the thread once. Their mission was completed back at Michael's again. Then they both laughed. They were always laughing. They just saw the funny side of things in the same sort of way.

Another time, Michael said, "Let's go and see my Nan."

"Where does she live?"

"Not far, I know the way," said Michael. "We'll go on our scooters."

"What will our Mams say?"

"Don't worry! It'll be worth it. My Nan always gives me some sweets."

"All right then."

It was a bit steep up Friar Street so they had to stop scooting and pushed their scooters up the slope. They stopped to peep in at the shire horses, which were kept on the left hand side, just across Moor Lane from Mitchell's, in Brewery Lane. The strong horses were used to pull heavy loads all round the town.

Some of the horses were in the shed which acted as their stable. One huge horse was tethered to a post in the middle of the yard. The boys peered at the animals through the spaces between the bars of the wide, high, iron gates.

"See that white one," said Michael, "My Nan's neighbour, Mrs. Wilson, used to own her, when she lived on a canal boat. It's called Florrie and she used to pull a barge."

"Big, aren't they?" said Rob.

"Yes, and they can hurt you," replied Michael. "Mam says I should never try to touch them or stroke them."

"That's all right," said Rob, "I don't want to really anyway do you?"

"No," said Michael, as one of the huge beasts stamped a heavy hoof. The ground shook beneath their feet and the gate they were leaning on rattled. That horse was a real giant.

On an impulse, Michael bent down and picked up a small stone. He threw it at the big horse but missed. It turned its head slowly towards them, more in curiosity than alarm Just then, by coincidence, a man emerged from the shed.

Michael thought he might have seen him throw the pebble. His heart stood still. His stomach turned over.

"Run!" he shouted at Rob. "He's after us!"

The man was only fiddling with the horse's tether but Rob needed no urging. The pair of them hurtled up the hill, dragging their scooters behind them.

There was a perverse pleasure in feeling they were being chased and escaping their pursuer. They liked having adventures together.

They crossed Dalton Square. In the middle of the square they took turns to climb up onto the few-inches-wide edge of the plinth, which supported Queen Victoria's statue. They both managed to go all the way round, rubbing noses on the way with the carvings of eminent Victorians, before they climbed down again to safety. Michael didn't tell Rob that was the first time he'd done it, without his mother helping and waiting to catch him, if he slipped.

They managed to cross the main road without any problems because there was hardly any traffic, even though it was one of the main roads, north and south, through Lancaster.

They passed the end of George Street. They paused and watched a clogger in a leather apron working near the window of the clog repairers in Thurnham Street. The man smiled at them and went on fitting strips of iron to the wooden sole of a clog. The boys turned into Marton Street. Nan's was at the near end and she was really pleased to see them.

She gave them some sweets from the tin which she kept in a cupboard. They sat quietly next to each other on her settee while Nan went on with what she'd been doing.

They watched her take some bread out of the oven at the side of the fire. She turned her bread tins upside down on the well-scrubbed, wooden table and lifted them. Under each one was a fresh loaf.

"Done to a turn. Risen nicely they have!" Nan declared, wiping her hands on her apron, after inspecting her baking for flaws. The aroma from the bread made the boys' nostrils twitch. It smelt lovely. They had an unexpected bonus, when she laid some butter on thickly and gave each of them a bit of the crust off one of her still-hot loaves.

"Just a taster each," said Nan. "Tha mustn't spoil tha teas or I'll have your mothers after me."

They still sat close together on her settee contentedly, eating the bread, sucking the sweets, swinging their legs, talking to Nan.

Then Michael's and Rob's mothers arrived, both frantic, after searching all over the place for the two boys. There was a terrible row. Margaret blamed Nan for the boys' going missing.

"I didn't know they were coming. It's nothing to do with me," Nan protested. "I thought you'd let them come."

"Course I didn't! Would I do that, with that main road to cross?"

"Well it did cross my mind that it was a bit funny but you young ‘uns are always doing funny things."

That did it: they had a real set to.

Michael was smugly pleased. Any anger at what they'd done was turned away from him and he felt satisfied that he was the cause of the commotion. Nan was secretly happy because her grandson had had the urge to come and see her. And she really enjoyed having a go at the silly young thing who had married her Gordon. It was about time that she was put in her place, brought down a peg or two.

Only Margaret lost out, especially as she'd had to beg Next-door to keep an eye on the babies' prams in the yard, while she and Sheila Matthews went looking for the missing boys. Only that morning she had vowed to herself that she wouldn't talk to her unfriendly neighbour again, after further complaints, this time about Margaret overfilling her dustbin and letting rubbish blow about the shared yard.

When Gordon arrived home that evening, Margaret's eyes were still red-rimmed because of all her crying. She poured out her troubles to her husband.

He felt aggrieved. He didn't want to be greeted with all that nonsense. It wasn't the first time and it wouldn't be the last when he felt like piggy-in-the-middle between his wife and mother. He said as little as possible in response to his wife's moaning. "Least said, soonest mended!" he thought.

Web Links of interest

• The English Clog Maker or Clogger

• There are only a very small number of clog makers left from the many hundreds who traded in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Cloggers still trading include Jerry Atkinson, Mike Cahill, Walter Hurst, Trefor Owen, the Turtons, and the Walkleys

• Opened by Samuel Greg & Company in 1826, the steam-powered

cotton-spinning Moor Lane Mill, where Celia worked, was taken over (and fireproofed) by Storey Bros.,

one of Lancaster's leading firms, in 1861. Storeys ceased trading in 1982, and after a period of dereliction then

Council-funded restoration the Grade II Listed mill became the UK

headquarters of Reebok, the sports and footwear company, in 1990. More

recently, it has become NHS offices.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)