|

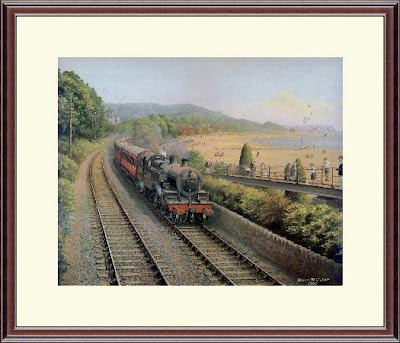

| • Summer Time painting by Tom Dodson. Reproduced with permission courtesy of Studio Arts, Lancaster |

They left Castle Station and its mock-Elizabethan architecture behind and moved off jerkily at first, then more smoothly as the engine got up-steam.

"Mam! Mam! We're crossing Carlisle Bridge," cried Michael, hoping for a bird's eye view of his school. For once, he was enjoying the crossing. Being on a train was different from being on the footbridge and dreading its shaking by a train. He moved over to Gwyn's side and looked back, hoping he'd be able to see St Mary's. He had the merest glimpse of it on the far bank of the Lune. Then they were picking-up speed and heading past Ryelands and Hareruns Estates and the Padfields.

It was a lovely journey, probably one of the best anywhere in the whole wide world. They were close to the sea at Hest Bank and had a view of the Bay and the Pennines on the other side of the water. After the busy railway junction town of Carnforth they went on to Silverdale, as lovely as its busy pretty name. Next, it was Arnside and Grange-over-Sands, which meant they were half-way to Barrow.

It was dusk and there was a spectacular sunset in the west over the Bay. They watched the sun kiss then sink down behind the Lakeland hills. The slowly darkening clouds were decked with a glory of colour – a technicolour spectacle, all the way from the horizon and right over the train. It was as good a sunset over Morecambe Bay as ever inspired the likes of the painter Turner. The tide was in, the sea reflecting the luminous sky, as they went over the water on a long viaduct.

After the sun was long gone and the landscape was quite dark, the clouds over the Bay still had faintly glowing colours, like the embers of an almost defunct fire.

"Mam! Mam! We're sailing over the sea!" chortled little Gwyn. It was true. Enough light remained for them to see the water below. Both she and Michael stood up in amazement. It was quite a distance before they were travelling over dry land again. Michael had not been too worried about the train toppling down into the water but the possibility had crossed his mind.

Margaret pointed out the strings of glittering sparklers which were distant Morecambe's lights. "Look," she said, " those lights! They go for miles along the promenade."

On they steamed to Kents Bank, Ulverston, Dalton, Roose and finally to Barrow. They had completed a magic-makers semi-circle of about fifty miles right round the Bay.

Michael had been mystified when he spotted a lighthouse high on a hill, on the land side. He'd seen a picture in one of his books of one on a rock, out at sea. He thought lighthouses were situated off the coast, to guide ships away from rocks. You couldn't have ships sailing near hills. His Mam couldn't enlighten him. It was the stimulus for another of his weird dreams, with ships going over mountains.

|

| Barrow Central Station before World War 2. Image via the South Lakes Memory Bank |

What made his day was seeing an old railway engine, in a big glass case, outside the railway station."Coo! Look at that, Gwyn!"

Uncle Tom said, "That's old 'Coppernob'. It used to run on the Furness Railway a hundred years ago."

It was beautiful, thought Michael. It looked superb, all shiny copper, brass and steel.

Grandma and Grandpop were ever so pleased to see them. When dark-haired Aunty Julia gave Michael a hug and told him what a big boy he'd become, he thought that she smelled nearly as nice as Aunty Joyce. But he didn't like the lipstick she left on his cheek.

Michael and Gwyn slept in the same bed. He dreamed a lot but didn't wake up in the night and they both slept late. When the grown-ups came to bed, Margaret and her mother looked in on them, lying side-by-side, heads nearly touching.

Beatrice said, "They're beautiful kiddies my dear. You're a lucky girl. You've a lot to be proud of."

James gave her a hug just like he used to do when she was his favourite little girl. It nearly made her cry, she was so happy. She was so pleased to have everything in her life, just as she'd always wanted it. Perfect children! Perfect house! Perfect marriage! Everything was quite wonderful!

She was to sleep in the same bed as her youngest sister. It was very late when Julia came into the bedroom. She woke Margaret up, stumbling around the room. Julia didn't smoke but there was the stale aroma of cigarettes from her when she laid herself down beside Margaret. Her breath smelled of gin. Margaret pretended to be asleep. She didn't want to talk to her boozy sister. She dozed off quickly. Julia's snoring in her ear didn't wake her. It had been a long day and she was very tired. She slept the deep sleep of the just.

In the morning, Grandpop, Tom and Julia went to work. Margaret and Gwyn went to have a look round Barrow. Michael said, "I want to stay with Grandma."

Beatrice was pleased and said so. Margaret left him behind. The real reason Michael wanted to stay in the house was not to be with Beatrice. He'd noticed the piano, the one James had bought for Julia. As soon as his mother had gone, he asked Beatrice if he could play the instrument. She smiled benignly on him.

"Of course you can my dear. I'll lift the lid for you. It's a bit heavy. Now mind you don't slam it down on your fingers!"

She went into the kitchen to do some baking. Michael had the time of his life. He banged the keys and sang and shouted along with his discords. It was just like the old days before Margaret got rid of the harmonium.

After half an hour, of listening to his row, Beatrice wished that he'd gone out with his mother!

"Would you like to help me bake Michael?"

"No, I'm all right, thanks Grandma."

Bang! Crash! Wallop!

After the three had come home from work, Margaret and Gwyn returned by bus from the town-centre. They all sat down to lunch together. Afterwards, Tom took them for a car ride. Beatrice stayed at home because she had a bit of a headache. Tom showed them the submarines that were being built at Vickers shipyard. they went over to Walney Island to look at Morecambe on the other side of the Bay.

"I wonder what Dad's doing?" Michael said.

"Getting stuck into the garden I suppose," said Mam.

"If he's stuck, he'll need me to pull him out," said Gwyn.

"Whatever he's doing, it's too far to see from here," laughed Tom. "Come on you kids, I'll race you to the ice-cream man."

They ate their ice-creams sitting on the beach. But it started to rain. So they went back home to Grandma's and Grandpop's. Grandpop was upstairs in bed. "Having forty winks," said Beatrice.

James went out in the early evening. The rest stayed in and played a card game, 'Happy Families'.

"Dad still likes his pint," remarked Margaret.

"Don't we know it!" sighed Beatrice. "He always will. He'll never change."

Michael and Gwyn stayed up very late. It was nine o'clock before Margaret said, "Time for bed for you two!" After the card game they'd played on the carpet. There were toys which Beatrice kept for when any grandchildren stayed with her. Some of them were really old. Michael liked the little wooden train which Grandpop had made many years ago. He would have liked to have kept it for himself but he knew he had lots of cousins who would want to play with it when they visited.

Gwyn's favourite was a china doll. Beatrice had made all the clothes for it, after she'd bought it in a second-hand shop, in Cardiff, in 1913. Michael enjoyed hearing about where all of the different toys had come from.

"Did you play with them when you were a little girl Mam?" asked Gwyn.

Beatrice answered for her, "Oh yes she did! Your Mam was ever such a good little girl. Just like you! There was nothing she liked better than playing quietly with her things. And she was always a good help for me with the little 'uns."

"Who were the little 'uns Grandma?" asked Gwyn.

"I was one," said Tom.

"And I was another," smiled Julia.

Gwyn found it hard to imagine her aunt and uncle as children like her brother and herself.

"Was that in the Olden Days?" she asked, thinking about some of her stories which began, "Once upon a time, long ago, in the Olden Days.."

Everybody laughed when she asked that. Tom said, "You trying to make me into an ancient monument my girl?"

Gwyn was puzzled by their reaction. She frowned at Tom and said, "I'm not your girl. I'm my Dad's girl."

"Not the Olden Days Gwyn! No, my lovely," said Grandma, "it seems more like only yesterday to me. Just like yesterday!" When she said it, she was thinking back to when all of the children were at home. She remembered the infants who had died. It made her feel and look quite sad.

"I'm a bit tired Mam," said Gwyn. "Can I sit on your knee?"

"Here," said Beatrice, "Come and sit on mine!"

Gwyn cuddled up to her and soon fell asleep.

Margaret repeated herself. It was time for bed! This time there was no way round it. They were both very tired. Their protests were not really meaningful. It had been a lovely day.

Playing the piano was what Michael had enjoyed most of all.

"I hope we'll see you again, soon, my lovelies," said Grandma when they left on the Sunday straight after lunch. Grandpop was back in the pub. but he'd left them a shilling each for pocket-money.

Mother and daughter hugged each other.

"Perhaps our Tom will drive you to Lancaster. You still haven't seen our new house," Margaret suggested.

Tom said, "It's a promise. I will when I have the time."

"Some promises are never kept!" thought Margaret, knowing what a full social life Tom had in Barrow.

Gordon was waiting for them when they arrived back in Lancaster.The two children ran along the platform and flung themselves at him, telling him all about what they'd done and what they'd seen. "It was a really good adventure Dad!" said Michael.

"Grandpop gave me a shilling!" said Gwyn.

"I'm pleased. You seem to have enjoyed yourselves," replied Gordon.

"It's nice to be back," Margaret said. "Anything interesting happen while we've been away? Managed to pass the time all right love?"

"It was a bit boring," lied Gordon. "But apart from that everything was fine. Come on, we'll walk! I bet we'll do it quicker than the bus."

He picked up their case in one hand and Margaret lifted Gwyn up, to be carried on his other arm. Her head rested on his shoulder. Gordon strode out for home.

"I'm your best girl aren't I, Dad?" Gwyn asked.

"You certainly are my love," replied Gordon, giving her a squeeze.

"Not so fast Dad!" urged Michael.

"Slow down Gordon please! We can't keep up," pleaded Margaret.

"We'll have to keep going or the bus will beat us!" retorted Gordon.

"So what!" snorted Margaret. "What does it matter?"

It mattered to Gordon. He had to win his silly little games. It sort of helped to compensate for those other big losses. The father who had been killed! The absence of money when he was a lad! The education he'd never had! The lack of dignity at work!

When they arrived home, there was a lad who lived in Marton Street, waiting to see Gordon. "Hello Mr. Watson," he said. "Your mother's sent me to tell you. Henry's been took ill. He's in a bad way..."

|

"Coppernob" was the nickname given to Furness Railway Number 3 which hauled the first passenger train on the Furness Railway, and was placed in a glass case at Barrow Railway station on its retirement. It was removed during the Second World War after the station was bombed, and is now a valued exhibit at the National Railway Museum in York. |

• Summer Time painting by Tom Dodson. Reproduced with permission courtesy of Studio Arts, Lancaster

• Furness Railway Trust

No comments:

Post a Comment