Discover a marvellous trip back to Lancaster of the past by author Bill Jervis, which we plan to release in weekly segments. Although the story is set in Lancaster the family and most of the characters within are entirely fictitious -- but this story does chart a way of life largely lost and which many Lancastrians may recall with equal horror and affection...

Sunday, 4 September 2011

Chapter 6: Sunday Morning

One bright Sunday morning in December, Michael lay awake in his bed thinking. "It's not fair, I'm here all on my own, just because they have a baby."

From the other bedroom, there came his Mam's quiet singing and soothing words as she fed Gwyn. The baby was crying. It seemed to Michael that she spent most of her time crying. He was fed up with having to be quiet when she was asleep and having to be silent when his mother was trying to coax her to sleep. All she did was lie in her pram or cot or be carted about in his mother's arms. She was a dead loss. She was boring. She couldn't play any games. And she'd wet right down him when his Mam once asked him to hold her. Blooming baby!

Why couldn't he go in there with them? It used to be great, he thought, jumping on their bed and using Gordon's knees to slide down. He liked snuggling between them in their warmth. Every Sunday morning it had been like that. "Having a good lie in," Dad called it.

Now, they said, he was too rough or too noisy when he went in there to play with his Dad. He might hurt the baby or disturb her.

"Huh!"

He quite liked being left on his own with Gwyn. He didn't mind being asked to look after her when Mam was busy. He enjoyed seeing her growing day-by-day. She was interesting because she was always doing something new. He was trying to persuade her to speak.

"Say Michael! Say Michael," he'd ask her and she'd laugh back at him and kick her legs at his coaxing. She liked it when Michael tickled her and shook her rattle for her.

One day, when he asked her to, "Say Michael!" she didn't just gurgle and smile back at him, she went, "Mmmm."

Michael left her lying on the blanket in front of the fire and ran into the kitchen. "Mam! Mam! She said it! She said my name!"

Michael was delirious with excitement and pleasure.

She was still a bit young for that to have really happened, thought Margaret, but she was pleased. She could see that Michael really loved his dark-haired little sister. For a time it had worried her that he was not at all keen on having a baby sister who took up so much of her energy.

Yes, there were times when Michael thought Gwyn was really brilliant. But not on Sunday mornings!

Still lying in his bed, in his own room, he reached for his nursery rhymes book. He looked at the pictures and tried reciting the ones Gordon had taught him. It was no use: he was feeling too sorry for himself. He threw the book down, pulled the bedclothes over his head and said to himself again, "It's not fair! Not fair!"

From the dark, where he was hidden under the clothes, unexpectedly, he heard his father's voice, "Where's Michael? I wonder where Michael is?"

Michael stayed under the bedclothes and kept very still. He even tried holding his breath. Dad said, "I know where he is, he's gone downstairs."

Michael pushed the bedclothes back "No, I haven't! I'm here Dad, I was hiding from you."

Already partly dressed, Gordon lay down on top of the bedclothes. Laughing, he said, "Move over, you're taking up all the room. Now come on, I want to hear your nursery rhymes. Right?" Michael nodded eagerly.

And that's how it was every Sunday morning after that. His father came in, stayed with Mike, chatted with him and helped him dress. Then they went downstairs together, lit the fire, washed in cold water and made a cup of tea. Michael didn't like tea so he had a drink of water. Gordon took a cuppa up to Margaret.

Then they had their porridge. Gordon ate his quickly and went outside to the lav. It was a double-seater, in the shed, in the yard, the one they shared with Next-door. Michael hated it in there because underneath the seat there was a deep hole and nasty smells came up. He was terrified of slipping down into that hole. He wished he could still be allowed to sit on his potty. It was all right for Gwyn. She didn't have to sit out there in the cold all by herself!

After he'd met his new friend Rob, he warned Michael, "Sometimes rats come up out of that hole. Mind they don't bite your bum!"

"You're only kidding me, aren't you Rob?"

"Suppose so," said Rob.

While Michael was carrying on eating his breakfast, he heard an angry voice outside. It was Next-door having a go at Gordon because, she said, Margaret wasn't keeping the wooden seat of the shared lav. clean enough. It wasn't true, because Mike had seen his mother scrubbing with carbolic soap and a stiff-bristled brush out there nearly every day. He didn't like the sickly smell of that carbolic.

"Well, just you tell your missus, it's time she mended her ways. All you young 'uns think on is lounging about, doing nowt, while us old'‘uns does all the work."

It went on like that until Gordon became fed up, left her to ramble on, and came in. He hadn't said much in reply. He wasn't one for trouble. Silent, in contemplation, he put the kettle on the fire again. He needed more hot water because he shaved straight after breakfast on Sundays. Michael loved to watch him, but he didn't like it when, sometimes, Gordon lifted him up and rubbed his unshaven cheeks against Michael's, really hard. It was just like sand-paper! Michael always screamed and Margaret would shout at his Dad from upstairs to stop it. So Gordon put him down.

When Margaret came for her breakfast and Gordon told her about Next-door, Margaret wasn't worried.

"Oh she's always at me! Best take no notice! She's a fine one to talk. Dresses like a scarecrow and smells like a drain! She's all on her own. Nothing else to think about!"

Labels:

Edward Street,

Lancaster,

Sunday Mornings

Saturday, 3 September 2011

Chapter 5: Edward Street

Michael's father was a strong man with muscular arms and hairy legs. He had dark hair, weather-beaten features, and the bluest eyes you ever saw. His wife's friend, flighty Joyce, the one he used to have it away with before he met Margaret, said he had the nicest eyes she'd ever seen in a man.

Gordon could be moody occasionally but he rarely lost his temper. His and Margaret's was a love-match. Sometimes, they disagreed and fell out, Margaret alway found it was difficult to have a real row with Gordon. She might rave, but he would go quiet and sulk. It excited both of them when they rowed, though. After it was over, they usually made love.

Gordon enjoyed sex but didn't get enough of it. Sometimes, when he felt particularly frustrated, he wondered why he'd married. He'd had more of it when he was single. But he kept these thoughts to himself...

Gordon had two alarm clocks by his bedside. The extra one was there in case the first one failed to ring. He dare not be late for work. To ensure being there in time, he had to set out at six every morning. It was a long walk. He carried his lunch box and a rubber cape and leggings, in case it rained. In all seasons, he wore a flat cap when he went to work, one with a check pattern on the top. He was a craftsman so he wore a tie.

It was nearly two miles to where he worked at Williamson's lino factory. Many still called it the Shipyard, although linoleum had been made there for donkey's years. Gordon's long stride meant that he overtook many other workers on his way. He used to set himself a target as he left home, of how many he would pass on his way to Williamson's. Sometimes, he ran the last few hundred yards in order to meet his arbitrary target.

"Why's he running?" a mate who saw him would think, "We're not late?"

Working days, Margaret was always first up, her footsteps light on the stairs. There was the scratching of a match and soon, crackling from the wood, under the coal on the fire. Gordon always laid it the night before. The next thing Michael heard was the sound of his Mam filling the kettle to boil hot-water. Margaret brewed the first cup of tea of the day and made a bowl of hot porridge, to send Gordon off warm to work.

Even at that early hour, you could hear the machinery, in the mill, behind their Edward Street house, humming away. Twice a day, that mill's buzzer would sound, a sort of siren, to warn the workers that they had better hurry or they'd be late. That would mean, without exception, a punishment: a docking of wages, for a few minutes lateness; or a sending home, for a day without pay. Worse still you might get the sack, especially if one of the bosses didn't like you.

Some still paid a knocker-upper to bang on their bedroom windows with his long pole, to make sure they got out of bed promptly. He was a legacy from, not that long previously, when few had watches or clocks or could not tell the time. When Gordon hurt an ankle, playing football,for the works team, he worried even more about being late. He left the house half an hour earlier, every morning, because he could only limp there slowly. He kept that up for six weeks, in agony every day. Thankfully, the ankle mended. But he packed in playing soccer. He couldn't afford to have time-off, if he was injured. It was the same if he felt ill: somehow, he always struggled into work.

The buzer for afternoon work, in the mill up Moor Lane, fascinated the infant Michael. When he heard it, he'd persuade his mother to open the parlour door of their two-up and two-down house. She'd put one of their bent-wood chairs up against the window. She'd place a cushion on the chair and lift Michael on to it. He'd kneel there and watch what happened in the street.

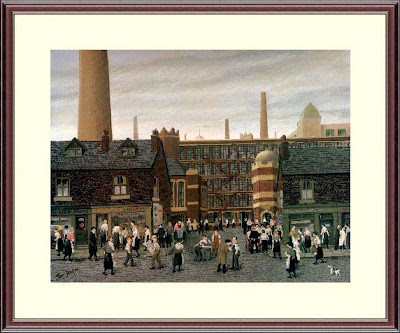

As if by magic, people appeared outside and passed the window. They looked like Lowry's matchstick people. Nearly all wore dark clothing. They shuffled past and headed round the corner of Moor Lane. Some were wearing clogs, which clattered on the pavement, and a young lad would occasionally kick the cobbles of the road and make sparks fly, as the metal on the soles of his clogs smacked against the stones. Latecomers hurried past and finally, there was the odd scampering boy, his face anxious, determined not to be late, for fear of losing precious pence.

After the last one had gone, Mike would call to his mother to lift him down. He had power over her, exercised it mercilessly and she didn't seem to mind. His slightest wish, his every whim was catered for by his Mam. She had to jump to it or he'd moan at her or cry! Gordon thought that she pampered him too much.

After his sister was born, things changed. Quite a bit! Like, when he called to her to lift him off the chair, when all the workers had gone by.

Sometimes, she'd respond, "You'll have to wait a minute, I'm just changing a nappy!" or "I'm feeding the baby!" and finally, "You're big enough and old enough to get down yourself! And don't forget to put the chair back in its right place!"

He liked to kneel on the chair in the parlour at other times. He might look out through the window and look at the horse-and-cart which brought the coal. The coal-man used to put a nose bag on the horse outside theirs. The old horse would have a bit of a rest and a feed while the hefty, grimy, coal-man lifted the hundredweight bags off the cart. He'd prise open the cellar cover, which was let into the pavement, push it out of the way, ease the bags of coal over the hole and coax the fuel out. He'd let it tumble down into the cellar. When he'd finished, there would be coal dust all round the cover. It would not be there for long. It would soon be swept away by Michael's mother, the zealous housewife. The cleanliness of your stretch of stone flags was as important as your personal hygiene. Emblems of pride or shame!

Looking out onto the street was a thing to do when Michael was bored. Something else was ‘playing' an old harmonium which was kept in his bedroom. One of his great-aunts, who lived further down the street, had given it to the Watsons. Everyday, Michael liked to have a go on it. He had to stand up to reach the keys. He gave them a real bashing. He would sing along tunelessly with the discords he was creating.

His mother used to shut the living-room door, to keep most of the noise out. She was glad to have him amusing himself and not needing her to amuse him. Unexpectedly, and in Michael's view, unreasonably, a stop was put to his playing. It was, "You'll wake Gwyn up," or "I'm trying to get Gwyn to sleep." He didn't take a lot of notice but carried on going upstairs and hammering away at the organ whenever he felt like it.

She insisted, so he put on his parts. It was a daily battle which went on for weeks. It was solved when Margaret offered the organ to one of her sisters who lived in Lodge Street. Michael's Uncle Joe came with another man and took it away. Gordon had to hold tight to Michael until they were out of the house. He was kicking and struggling to be free.

"It's all her fault," stormed Michael, pointing at Gwyn lying happily in her pram, "I hate her."

Gwyn smiled and kicked her tiny little legs about. Michael shook a handle as hard as he could making the pram rock. And that made Gwyn gurgle with delight all the more!

"Michael! Behave yourself!" said Margaret.

"Huh!" responded Michael. He fetched his toy rifle and pretended to shoot both of them.

"Michael! I've had about enough! Just you wait ‘til your Dad comes home!"

"Huh!"

• Dinner Time at the Mill painting by Tom Dodson. Reproduced with permission courtesy of Studio Arts, Lancaster. All other images © Bill Jervis

Gordon could be moody occasionally but he rarely lost his temper. His and Margaret's was a love-match. Sometimes, they disagreed and fell out, Margaret alway found it was difficult to have a real row with Gordon. She might rave, but he would go quiet and sulk. It excited both of them when they rowed, though. After it was over, they usually made love.

Gordon enjoyed sex but didn't get enough of it. Sometimes, when he felt particularly frustrated, he wondered why he'd married. He'd had more of it when he was single. But he kept these thoughts to himself...

Gordon had two alarm clocks by his bedside. The extra one was there in case the first one failed to ring. He dare not be late for work. To ensure being there in time, he had to set out at six every morning. It was a long walk. He carried his lunch box and a rubber cape and leggings, in case it rained. In all seasons, he wore a flat cap when he went to work, one with a check pattern on the top. He was a craftsman so he wore a tie.

It was nearly two miles to where he worked at Williamson's lino factory. Many still called it the Shipyard, although linoleum had been made there for donkey's years. Gordon's long stride meant that he overtook many other workers on his way. He used to set himself a target as he left home, of how many he would pass on his way to Williamson's. Sometimes, he ran the last few hundred yards in order to meet his arbitrary target.

"Why's he running?" a mate who saw him would think, "We're not late?"

Working days, Margaret was always first up, her footsteps light on the stairs. There was the scratching of a match and soon, crackling from the wood, under the coal on the fire. Gordon always laid it the night before. The next thing Michael heard was the sound of his Mam filling the kettle to boil hot-water. Margaret brewed the first cup of tea of the day and made a bowl of hot porridge, to send Gordon off warm to work.

Even at that early hour, you could hear the machinery, in the mill, behind their Edward Street house, humming away. Twice a day, that mill's buzzer would sound, a sort of siren, to warn the workers that they had better hurry or they'd be late. That would mean, without exception, a punishment: a docking of wages, for a few minutes lateness; or a sending home, for a day without pay. Worse still you might get the sack, especially if one of the bosses didn't like you.

Some still paid a knocker-upper to bang on their bedroom windows with his long pole, to make sure they got out of bed promptly. He was a legacy from, not that long previously, when few had watches or clocks or could not tell the time. When Gordon hurt an ankle, playing football,for the works team, he worried even more about being late. He left the house half an hour earlier, every morning, because he could only limp there slowly. He kept that up for six weeks, in agony every day. Thankfully, the ankle mended. But he packed in playing soccer. He couldn't afford to have time-off, if he was injured. It was the same if he felt ill: somehow, he always struggled into work.

The buzer for afternoon work, in the mill up Moor Lane, fascinated the infant Michael. When he heard it, he'd persuade his mother to open the parlour door of their two-up and two-down house. She'd put one of their bent-wood chairs up against the window. She'd place a cushion on the chair and lift Michael on to it. He'd kneel there and watch what happened in the street.

As if by magic, people appeared outside and passed the window. They looked like Lowry's matchstick people. Nearly all wore dark clothing. They shuffled past and headed round the corner of Moor Lane. Some were wearing clogs, which clattered on the pavement, and a young lad would occasionally kick the cobbles of the road and make sparks fly, as the metal on the soles of his clogs smacked against the stones. Latecomers hurried past and finally, there was the odd scampering boy, his face anxious, determined not to be late, for fear of losing precious pence.

After the last one had gone, Mike would call to his mother to lift him down. He had power over her, exercised it mercilessly and she didn't seem to mind. His slightest wish, his every whim was catered for by his Mam. She had to jump to it or he'd moan at her or cry! Gordon thought that she pampered him too much.

After his sister was born, things changed. Quite a bit! Like, when he called to her to lift him off the chair, when all the workers had gone by.

Sometimes, she'd respond, "You'll have to wait a minute, I'm just changing a nappy!" or "I'm feeding the baby!" and finally, "You're big enough and old enough to get down yourself! And don't forget to put the chair back in its right place!"

He liked to kneel on the chair in the parlour at other times. He might look out through the window and look at the horse-and-cart which brought the coal. The coal-man used to put a nose bag on the horse outside theirs. The old horse would have a bit of a rest and a feed while the hefty, grimy, coal-man lifted the hundredweight bags off the cart. He'd prise open the cellar cover, which was let into the pavement, push it out of the way, ease the bags of coal over the hole and coax the fuel out. He'd let it tumble down into the cellar. When he'd finished, there would be coal dust all round the cover. It would not be there for long. It would soon be swept away by Michael's mother, the zealous housewife. The cleanliness of your stretch of stone flags was as important as your personal hygiene. Emblems of pride or shame!

Looking out onto the street was a thing to do when Michael was bored. Something else was ‘playing' an old harmonium which was kept in his bedroom. One of his great-aunts, who lived further down the street, had given it to the Watsons. Everyday, Michael liked to have a go on it. He had to stand up to reach the keys. He gave them a real bashing. He would sing along tunelessly with the discords he was creating.

His mother used to shut the living-room door, to keep most of the noise out. She was glad to have him amusing himself and not needing her to amuse him. Unexpectedly, and in Michael's view, unreasonably, a stop was put to his playing. It was, "You'll wake Gwyn up," or "I'm trying to get Gwyn to sleep." He didn't take a lot of notice but carried on going upstairs and hammering away at the organ whenever he felt like it.

She insisted, so he put on his parts. It was a daily battle which went on for weeks. It was solved when Margaret offered the organ to one of her sisters who lived in Lodge Street. Michael's Uncle Joe came with another man and took it away. Gordon had to hold tight to Michael until they were out of the house. He was kicking and struggling to be free.

"It's all her fault," stormed Michael, pointing at Gwyn lying happily in her pram, "I hate her."

Gwyn smiled and kicked her tiny little legs about. Michael shook a handle as hard as he could making the pram rock. And that made Gwyn gurgle with delight all the more!

"Michael! Behave yourself!" said Margaret.

"Huh!" responded Michael. He fetched his toy rifle and pretended to shoot both of them.

"Michael! I've had about enough! Just you wait ‘til your Dad comes home!"

"Huh!"

|

| Edward Street, Lancaster today |

• Dinner Time at the Mill painting by Tom Dodson. Reproduced with permission courtesy of Studio Arts, Lancaster. All other images © Bill Jervis

Labels:

Edward Street,

knocker-upper,

Lancaster,

Williamson's

Friday, 2 September 2011

Chapter 4: A Birth

It was in the middle of the night that Margaret told her husband that her expected baby was on the way. Gordon dressed quickly, preparing to go for Mrs. Burnside, the midwife, and for the doctor.

"Take Michael with you," she urged. "I won't be able to help him if he wakes up and needs to go to the lav."

"Come on Michael," Gordon said, shaking his infant son awake.

"Why, Dad?" asked the resisting child, who was trying to turn over and go back to sleep.

"We've got to go for Dr. Ruxton. Come on, it'll be a good adventure. It's all dark outside."

He put Michael's jersey on over his night-shirt and tucked that into his short trousers. He took their winter coats from the hooks in the front passage and, wrapped up warm, they stepped out into the cold, dark night.

It was about half a mile to the doctor's and they knocked-up Mrs. Burnside on the way. "I'll go to there now," she told Gordon, peering down at him from her bedroom window. "Don't worry, I'll look after her. You go and try to fetch the doctor."

All of the lights were on in the doctor's house. Although he was worried for his wife, he noticed a car was parked not far away, with two people in it, sitting very close together. He couldn't see who, even as he walked past, carrying Michael to the doctor's front door.

As he knocked on the door, Gordon heard the car door slam and the car drove off. Almost immediately, Isabelle, the doctor's wife, was standing beside them.

Gordon just had time to say, "Hello Mrs. Ruxton," before the front door opened and the doctor appeared in the entrance. He completely ignored Gordon and Michael. His face was contorted with rage as he dragged his wife into the hall.

Gordon looked on stunned as he watched the doctor grab his wife by the throat and start snarling at her.

"You bitch!" he almost screamed. "You've been with him again haven't you? Don't you know what time it is? You're just a whore! You're a prostitute. Who was it this time? That bloody Bobby Edmondson?"

He still had her by the throat with one hand and now Gordon saw that he had a knife in the other. "Hell!" he thought, "doctors don't behave like this. What is going on?" Isabelle couldn't speak, Buck's grasp was so tight. Her eyes were bulging. She was struggling hard and managed to break free. She ran up the stairs, her husband shouting and swearing at her as she went.

Watching her go, the doctor looked at Gordon, almost as if he'd just noticed he was there for the first time. He seemed to make tremendous effort to pull himself together, calming down as he greeted Gordon.

"So sorry, Mr. Watson," he murmured. "Just a little something between a man and his wife. Why are you here?"

Gordon explained and the caring professional, who Gordon was familiar with, made all the right kind of reassuring noises.

"You go on home. I will be with you in a few minutes. I will take care of everything. Hello, Michael! You are out late."

Michael turned his head away and buried his face in his father's neck.

Gordon wondered if it was safe for him to leave Mrs. Ruxton with what had seemed to be a madman only a minute or two ago. But he was more worried about his own wife to think of the doctor's for long. "All right," he replied, coming to a decision. "We'll be off back home then. My wife is having a lot of pain. You will be coming?"

"Of course Mr. Watson. Pain is usual. Don't worry. She will be fine. I will be there within minutes. I have never lost a baby yet in Lancaster."

Gordon carried Michael back home. Mrs. Burnside was already upstairs with Margaret. The big kettle was boiling on the open fire. The lid was lifting and water was spilling out and making lots of steam when it landed on the coals. Gordon placed Michael in the big armchair next to the fire. He lifted the kettle and put it onto the bricked hearth, using a dampened cloth round the hot handle. Then he went upstairs to his wife.

"You stay there, our Michael. I'll be back in a minute."

Michael felt upset. He sat in the chair crying. His mother was screaming upstairs. He'd just seen nice Doctor Ruxton being nasty to Mrs Ruxton. He liked her a lot. At Christmas, he'd been to their house. They had a lovely big Christmas tree .

"The biggest in the whole world," little Billy Ruxton had said to Michael. Billy was the same age as Michael. Michael liked him too. Before they went home, Billy's mother had given all of the children, who had been invited, lots to eat and a present to be opened on Christmas day. It was a good present six packets of all different sweets.

There was a knock on the front door. Dad came down the stairs, went along the front passage and opened it for Dr. Ruxton. The doctor went up on his own. Gordon returned to Michael who had his hands over his ears and was sobbing. He was trying to stop hearing his mam's cries.

Gordon sat him on his knee and hugged him and rocked him, until he calmed down a bit.

"Dad, is Dr. Ruxton, hurting Mam?"

"No, of course not. He's helping her. Just like he helped you when you were ill. You know Dr. Ruxton, he wouldn't hurt a flea."

Until half an hour ago, Michael would have agreed, remembering the times he'd been to see the doctor in his surgery, in Dalton Square. The Doctor had three kids of his own and he was good with all children. He used to warm his hands before he examined you. He was very gentle with children. There would be a broad smile on the popular Parsee doctor's dark face when he'd finished.

"The best cure for this young man is a bottle of pop Mrs Watson was his usual verdict. "Don't you agree?"

Pretty Mrs Watson agreed.

Although he was tired, Michael did not fall asleep. He was watching and listening to everything that was going on. He knew that it was something important and to do with having a new brother or sister. But why his mother was screaming, something he'd never heard before, he could not understand. He wanted to go and see her but his Dad wouldn't let him.

The door which led to the cellar steps was set in the wall on one side of the living-room. Gordon took the coal bucket and went down into the cellar for more coal to put on the fire. At least, they were warm and cosy and there was quite a good light from the new gas-mantle over the mantelpiece.

He tried reading to Michael. But Mike could not settle. No question of falling asleep even though it got to four o'clock before his mother's shrieking stopped. The bedroom door opened and Michael heard a baby cry. The midwife told Gordon that he could go up and see his wife.

She sat with Michael and told him, "The stork has brought you a lovely little sister. Aren't you a lucky, big boy?"

Michael wasn't so sure about that. All he knew was that his mother had stopped screaming and he felt a bit better.

Dr. Ruxton popped his head round the living-room door and smiled at Michael, "Well young man, you've had quite a night. Mrs. Burnside can take you to see your new baby sister now. Then you can go off to Dreamland. Bye now!"

Michael turned away and buried his head in a cushion. He didn't like Dr. Ruxton anymore. Mrs. Burnside took him up to his new little sister, a tiny scrap, with a wizened face, all wrapped up in white linen and snuggled up to his mam. His mother looked tired and weary but she had a nice smile on her face.

"Come along Michael, have a good look at your sister. We're going to call her Gwyn." He gave his mother a kiss. Mrs. Burnside gave him a hug and told him, "You're a good lad, Michael."

His Dad took him back into his own bedroom and tucked him into bed. He didn't need the usual story because he went straight off to sleep.

• Read more about Buck Ruxton's house in Dalton Square

• The New Baby painting by Tom Dodson. Reproduced with permission courtesy of Studio Arts, Lancaster

Thursday, 1 September 2011

Chapter 3: All Change

In 1935, Michael Watson was a lively infant who loved his home, his Mam and Dad and all of the other people in his life. His first two years had given him nothing but lots of affectionate routines and unchanging, consistent security. When he began to understand that his parents were saving money, planning to move, he protested, "I don't want to move. I like it here!"

He had no immediate worry on that score. It would take them three more years to save for a deposit on a new house.

Every weekday, without fail, at the same times, the town’s factories' buzzers went. All day, The Watsons' house vibrated ever so gently, never stopping, because there was a mill, with humming machinery, just above and behind Edward Street, where they lived.

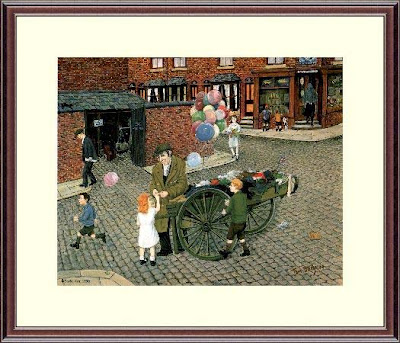

Sometimes there would be the clatter of horses' hooves, or of clogs on their cobbled street. Carts carrying coal, supplies for corner shops or crates of milk or fizzy pop would occasionally rumble over the cobbles past the house. There was hardly ever a car to be seen, unless a doctor visited a very sick neighbour. Just once, there was a funeral procession with three cars, filled with people all in black.

Once a week, the dust-cart, pulled by an old, unhappy-looking grey horse, would wait outside the Watsons'. Corporation employees, in brown dungarees, with sacks over their heads and draped over their shoulders, would go down the side and back alleys and bring out the bins filled with ashes, from the coal fires, and all sorts of other household waste. They'd empty the contents onto their cart, eyes seeking any item which they might be able to retrieve and sell on. Then they'd take the empty bins back to outside each house’s backyard-entrance. There was always a horrible smell in the street for about an hour after they’d been.

Every evening, at dusk, a tall, Lancaster Gas Works employee, in heavy boots, would walk past. He was a tall man with a short ladder. He would prop his ladder up against the lamp-posts, one on Michael's side of the road and one down near St. Anne's School. He’d climb his ladder, open the hinged window of the gas lamp, turn the gas tap round and illuminate the street. He would return at every dawn and turn the lights down.

Every morning, some of the women of the street would appear outside the front doors of their two-up and two-down terraced houses, built with local stone. They would scrub their doorstep and whiten it, wash the pavement's flagstones outside their front door, as far as the kerb, and sweep the rest. Once a week, they'd clean their windows and whiten the windowsills. Friday evenings, at seven o'clock, there would be a knock on the front door.

"Margaret!" Gordon would call, if his wife was working out in the kitchen, "Insurance man!" Margaret would stop what she was doing and let rain-coated, thin-haired, stammering Mr. Smith in. Margaret would hand him three books and three separate insurance payments, all ready, waiting for him, on the mantelpiece, all calculated correctly to the last penny, no change needed.

"Thank-you, M...M..Missus. See you next week."

An ice-cream man passed their front-door twice a week in the summer. He had a fridge mounted on a modified tricycle. He pedalled slowly and bumped over the cobbles. He called out every few seconds, "Stop me and buy one!" His fridge was white with the letters LOVELY ICE CREAMS painted in black diagonally across it. He'd always say, when Margaret bought from him, "There you are love! One for you and one for the spring chicken!"

"What's a spring chicken Mam?"

"You are. Now go inside and eat your cornet. And don't spill any on the lino!"

Every Saturday afternoon, the loud ringing of a hand-bell would be heard in the house. It signalled the arrival of the Muffin Man in the street. Sometimes, Margaret would buy from him. She would toast them in front of their open coal-fire. When Michael grew older she would let him hold the metal toasting fork.

When the crumpets or muffins were ready and placed on plates, warmed in the oven by the side of the fire, fresh Empire Butter was spread over them. Scrumptious!

On Christmas Day, in 1935, just before lunch, it was snowing, and an old man, with a beard and dressed in a ragged coat and old hat, limped down the street playing Christmas carols, on a squeaky violin. It was like looking out onto a Victorian Christmas card. He had a card strung round his neck, with a tin mug attached to it.

Michael stood in the parlour watching him. The old man winked at him. Margaret gave him a penny. Michael took it out to the old man and put it in the mug hanging from his neck. He had a card hanging from his neck too. Michael was too young to read it. It said, UNEMPLOYED EX-SERVICEMAN.

There was another man who frightened Michael. He came down the street once a fortnight. He carried a sack over his shoulder with lumpy things in it. He was tall and fierce-looking. His skin was spotty and he had lots of stubble. Once, when Michael was looking out of the window at him, he shook his fist, rolled his eyes and leered at Michael.

As he strode past each house, he called out in a loud sonorous voice, "Rags! Bones!"

When Michael got to know his first childhood friend, Rob, he told Michael that the man kidnapped babies and put them in his sack.

Gas mantels sputtering and hissing. Steam trains panting, shrieking, shunting and grunting. Signals clanking, guards waving flags and blowing whistles. Kids out in the streets yelling and shouting. Gossips whispering on many doorsteps. Taps on bedroom windows of early-morning knocker-uppers. Brown corporation and red Ribble buses revving up their engines and crashing their gears.

Lads, yelling warnings, "Mind your backs!" pushing barrows in out of the market. Thousands of people walking in sunshine or rain to and from their workplaces. Sunday afternoon strolls into the countryside. The parks filled in summer with families.

Surely, young Michael had thought, all of this will last, will endure for ever. It's all necessary, all part and parcel of my life. How could it ever change?

50 years later, the Edward Street houses were nearly all demolished, the school closed, the corner shop vanished and the whole area turned into a car park.

The Greyhound Bridge no longer carried frequent steam and electric trains: it was a road bridge. Green Ayre Station, a lovely building, and its wide forecourt, gone. The sidings, with coal wagons; the coal merchants next to the railway, the old National School building on Parliament Street long destroyed and the debris taken away.

No more kids pulling prams or buggies with loads of cheap coke from the Gas Works to their homes, to augment their meagre and more expensive coal supplies.

No more working horses.

The Children’s Home and The Spike, part of the old Workhouse, above the town, up near Williamson's Park, were now part of an extended Boys' Grammar School.

The old mills had closed but some were saved from demolition when Authority decided they were architectural gems and worthy of grants for their preservation and conversion.

The list of sights, from Michael’s childhood, now vanished for ever, seemed endless.

Cars infiltrate everywhere. A few streets are for pedestrians only. Technology dominates! TV, 'phones, hi-fi, computers. Big Brother cameras watching. Enticing shop windows displaying goods, stimulating wants rather than reminding you of what you need.

Soft shoes or trainers, (no clogs or boots). Colourful clothes (no woollen shawls). University students and some black or brown faces.

Musak!

Kids bossing their mothers in the street. Once it would have been described as,"Showing me up like that!"

Cafes! Restaurants!

Supermarket and roads where there was once a railway station, engine sheds and sidings. Some things were the same. Trains (diesel) still rumbled over a renovated Carlisle Bridge. The River Lune still lapped at high tide against St George’s Quay. Inland seagulls occasionally screeched overhead. Customers still mingled and chattered in the new market just like their grandmothers had in the old one.

It wasn’t all change. Some things were better, some worse. Nostalgia could be tinted with rosy colours.

Michael learned, after a couple of days of his visit, that much tangible evidence of his early life in Edward Street had vanished. Worst of all was his inability to find people who had known him, or his family, 50 years ago.

He awoke in the middle of the night in the Castle Hotel and began to think that he might have been better off staying at home. His vivid memories would never change. Back in Lancaster, he seemed to be losing his past rather than regaining it. Nevertheless, during the day, he went round the town taking photographs, did some sketching and began to write down some of what he remembered of his own childhood. He recalled what his family had told him, about their lives in Lancaster, in the decades before the end of the War in 1945. As he wandered around, old associations were revived. Places began to remind him of much he had forgotten.

Old memories were beginning to circulate again in his consciousness.

Michael's father was born in Marton Street, Lancaster, in 1904. He lived, until he married, with his mother and brother, in a tiny terrace house. It was one of a row all condemned as unfit for human habitation.

Michael’s most vivid memory of being there was of something that happened when he was three years old.

The lav was out in the yard, in a shed, shaped like a sentry box. It was shared by six families whose houses all backed onto the yard. Each household had a key.

Michael needed to do 'number twos'. It took him a long time. Somebody banged on the door loudly, three times and a deep, bass voice shouted, "What the bloody hell are you doing in there? Baking a cake?"

Michael wiped his bottom on a bit of newspaper, pulled up his short trousers and tried to turn the key. But he couldn't.

In a tearful voice he said, "I can't open the door."

Bass voice urged him, "Take your key out of the lock and I'll open it from out here. And hurry up! I’m nearly pissing myself!"

Nan’s house used to stand where the new Police Station is now. There was a strong sense of community in that street, intensified by shared sorrows, after the deaths of so many of their loved ones during the First World War.

Margaret, Gordon’s pretty, dark-haired, slim wife, was born in Wales, in 1910, and moved, during the Great Depression, to lively Morecambe, where she was a young teenager, in the place which was a Mecca for the workers on holiday from inland towns. Morecambe holiday providers thrived and many prospered during the Great Depression.

Their son, Michael, was born in 1933, in Thurnham Place, just across the main road from the end of Marton Street. Michael was only two when they moved from there and he could not remember what it was like inside. A slum, the Place had been demolished many years ago.

Michael’s sister, Gwyn, was born in 1935, in Edward Street.

|

| Unchanged Lancaster today |

• Read more about Green Ayre Station from the Lancaster Archaeological and Historical Society

• Information about the history of Lancaster Castle Station

• The Old Town Hall and The Rag and Bone Man paintings by Tom Dodson. Reproduced with permission courtesy of Studio Arts, Lancaster

Chapter 2: An Ordinary Town

The varieties of

lechery, murder, violence, child abuse, thieving, racketeering, hypocrisy,

double-dealing, deception, profiteering, low wages, long hours, sackings,

cheatings, lying, one-upmanship, conniving, corruption and two-facedness which

Michael Watson knew and heard about during his Lancaster childhood probably

still thrive. The majority of local people still live their ordinary lives,

with their usual loving kindness often taken for granted, their good deeds

rarely publicised. It's not good news that sells newspapers!

After he'd moved

away, in 1951, Michael used to go back home every few weeks. His journey would

be by steam train. He’d catch the 6.30 p.m. from London Euston. There would be

many Irish passengers, going on to Heysham, to make the overnight crossing to

Ireland on the boat the Duke of Lancaster.

His parents would

be at Lancaster Castle Station, waiting for his arrival. His father of medium

height, a stocky figure, was still dark-haired, bright blue-eyed, peering

through the steam from the engine, looking for "Our Michael".

Grabbing his

suitcase, after a powerful handshake, it was, "Come on lad, hurry yourself

up -- we might catch the last L6 bus!"

The briefest of

pecks on his mother's cheek and they were off. Dad handed in their platform

tickets and Michael had his return-ticket snipped by the ticket-collector.

Out of the Castle

Station entrance, ignoring the taxis, "Too expensive for the likes of

us!" he'd stride off up the incline, over the bridge, down the hill, along

China Street, down another hill to the bus-station. Just in time to see the red

Ribble bus disappearing down Cable Street, past the old baths towards

Parliament Street.

"Never mind lad, it's not far to walk!"

Off again along

St. George's Quay, up countless steps and over Carlisle Bridge, across

Morecambe Road, up the hill, a short-cut past the prefabs and down the top of

Sefton Drive, before turning right into their street, next to the Crows Wood.

Michael was just

over six feet tall but he could not match his shorter father’s longer stride.

His poor mother was soon quite out of breath.

"I don't know

what all the hurry is, Gordon. I can’t keep up with you. I'm trying to have a

word with our Michael."

Undeterred, Gordon

marched ever onwards, still carrying Michael’s heavy case. All Gordon’s life he

had had races to be won, self-imposed targets to be achieved. He never had much

to show for all of his efforts, except some personal satisfaction. At the end

of the day, perhaps that’s all that matters.

"15 minutes!

We did it in 15 minutes!" he cried triumphantly, plonking the suitcase

down and glancing at his watch, before taking out his front door key and

letting them in.

He pushed Michael

and his mother ahead up the hall, past the papier mache bowl on a stand, the

one Michael had made at junior school.

"We are just

as soon as the bus, seeing as how we'd have had to walk from Scale Hall Corner.

We’ve lost no time. And we saved on the bus-fares!

"Now come on

Margaret, make us a nice cup of tea. Michael will be tired after that long

journey!" "Not to mention the long, knackering walk!" thought

Michael. But he kept that to himself. It was only too easy for he and his Dad

to start arguing about something or, more usually, about nothing!

Many years passed,

and Michael prospered. In 1983, it was more than 20 years since he'd been on a

train. He had his own car. He decided firmly to go to Lancaster alone. He'd

leave the family at home. They lived out in the country but his wife had a

vehicle too. She wouldn't be left in lonely isolation.

He needed some

time on his own, time to go and find a part of himself all over again. Time to

explore the foreign country of his past.

He drove to

Lancaster in just over five hours, parked near the railway station and booked

into the Castle Hotel, on China Street. It was great to be greeted by the old

familiar local accents of the landlady and a chatty customer.

Michael lay awake

most of the night, contemplating his first impressions and what they had told

him. In some ways the place had been transformed. He recalled how it had been

when he'd lived in Lancaster's, Edward Street, in the far away time before the

Second World War...

• Information about the history of Lancaster Castle Station from the Lancaster Archaeological and Historical Society

Location:

Sefton Dr, Lancaster LA1, UK

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)