In 1935, Michael Watson was a lively infant who loved his home, his Mam and Dad and all of the other people in his life. His first two years had given him nothing but lots of affectionate routines and unchanging, consistent security. When he began to understand that his parents were saving money, planning to move, he protested, "I don't want to move. I like it here!"

He had no immediate worry on that score. It would take them three more years to save for a deposit on a new house.

Every weekday, without fail, at the same times, the town’s factories' buzzers went. All day, The Watsons' house vibrated ever so gently, never stopping, because there was a mill, with humming machinery, just above and behind Edward Street, where they lived.

Sometimes there would be the clatter of horses' hooves, or of clogs on their cobbled street. Carts carrying coal, supplies for corner shops or crates of milk or fizzy pop would occasionally rumble over the cobbles past the house. There was hardly ever a car to be seen, unless a doctor visited a very sick neighbour. Just once, there was a funeral procession with three cars, filled with people all in black.

Once a week, the dust-cart, pulled by an old, unhappy-looking grey horse, would wait outside the Watsons'. Corporation employees, in brown dungarees, with sacks over their heads and draped over their shoulders, would go down the side and back alleys and bring out the bins filled with ashes, from the coal fires, and all sorts of other household waste. They'd empty the contents onto their cart, eyes seeking any item which they might be able to retrieve and sell on. Then they'd take the empty bins back to outside each house’s backyard-entrance. There was always a horrible smell in the street for about an hour after they’d been.

Every evening, at dusk, a tall, Lancaster Gas Works employee, in heavy boots, would walk past. He was a tall man with a short ladder. He would prop his ladder up against the lamp-posts, one on Michael's side of the road and one down near St. Anne's School. He’d climb his ladder, open the hinged window of the gas lamp, turn the gas tap round and illuminate the street. He would return at every dawn and turn the lights down.

Every morning, some of the women of the street would appear outside the front doors of their two-up and two-down terraced houses, built with local stone. They would scrub their doorstep and whiten it, wash the pavement's flagstones outside their front door, as far as the kerb, and sweep the rest. Once a week, they'd clean their windows and whiten the windowsills. Friday evenings, at seven o'clock, there would be a knock on the front door.

"Margaret!" Gordon would call, if his wife was working out in the kitchen, "Insurance man!" Margaret would stop what she was doing and let rain-coated, thin-haired, stammering Mr. Smith in. Margaret would hand him three books and three separate insurance payments, all ready, waiting for him, on the mantelpiece, all calculated correctly to the last penny, no change needed.

"Thank-you, M...M..Missus. See you next week."

An ice-cream man passed their front-door twice a week in the summer. He had a fridge mounted on a modified tricycle. He pedalled slowly and bumped over the cobbles. He called out every few seconds, "Stop me and buy one!" His fridge was white with the letters LOVELY ICE CREAMS painted in black diagonally across it. He'd always say, when Margaret bought from him, "There you are love! One for you and one for the spring chicken!"

"What's a spring chicken Mam?"

"You are. Now go inside and eat your cornet. And don't spill any on the lino!"

Every Saturday afternoon, the loud ringing of a hand-bell would be heard in the house. It signalled the arrival of the Muffin Man in the street. Sometimes, Margaret would buy from him. She would toast them in front of their open coal-fire. When Michael grew older she would let him hold the metal toasting fork.

When the crumpets or muffins were ready and placed on plates, warmed in the oven by the side of the fire, fresh Empire Butter was spread over them. Scrumptious!

On Christmas Day, in 1935, just before lunch, it was snowing, and an old man, with a beard and dressed in a ragged coat and old hat, limped down the street playing Christmas carols, on a squeaky violin. It was like looking out onto a Victorian Christmas card. He had a card strung round his neck, with a tin mug attached to it.

Michael stood in the parlour watching him. The old man winked at him. Margaret gave him a penny. Michael took it out to the old man and put it in the mug hanging from his neck. He had a card hanging from his neck too. Michael was too young to read it. It said, UNEMPLOYED EX-SERVICEMAN.

There was another man who frightened Michael. He came down the street once a fortnight. He carried a sack over his shoulder with lumpy things in it. He was tall and fierce-looking. His skin was spotty and he had lots of stubble. Once, when Michael was looking out of the window at him, he shook his fist, rolled his eyes and leered at Michael.

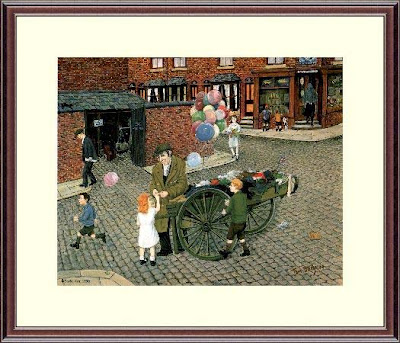

As he strode past each house, he called out in a loud sonorous voice, "Rags! Bones!"

When Michael got to know his first childhood friend, Rob, he told Michael that the man kidnapped babies and put them in his sack.

Gas mantels sputtering and hissing. Steam trains panting, shrieking, shunting and grunting. Signals clanking, guards waving flags and blowing whistles. Kids out in the streets yelling and shouting. Gossips whispering on many doorsteps. Taps on bedroom windows of early-morning knocker-uppers. Brown corporation and red Ribble buses revving up their engines and crashing their gears.

Lads, yelling warnings, "Mind your backs!" pushing barrows in out of the market. Thousands of people walking in sunshine or rain to and from their workplaces. Sunday afternoon strolls into the countryside. The parks filled in summer with families.

Surely, young Michael had thought, all of this will last, will endure for ever. It's all necessary, all part and parcel of my life. How could it ever change?

50 years later, the Edward Street houses were nearly all demolished, the school closed, the corner shop vanished and the whole area turned into a car park.

The Greyhound Bridge no longer carried frequent steam and electric trains: it was a road bridge. Green Ayre Station, a lovely building, and its wide forecourt, gone. The sidings, with coal wagons; the coal merchants next to the railway, the old National School building on Parliament Street long destroyed and the debris taken away.

No more kids pulling prams or buggies with loads of cheap coke from the Gas Works to their homes, to augment their meagre and more expensive coal supplies.

No more working horses.

The Children’s Home and The Spike, part of the old Workhouse, above the town, up near Williamson's Park, were now part of an extended Boys' Grammar School.

The old mills had closed but some were saved from demolition when Authority decided they were architectural gems and worthy of grants for their preservation and conversion.

The list of sights, from Michael’s childhood, now vanished for ever, seemed endless.

Cars infiltrate everywhere. A few streets are for pedestrians only. Technology dominates! TV, 'phones, hi-fi, computers. Big Brother cameras watching. Enticing shop windows displaying goods, stimulating wants rather than reminding you of what you need.

Soft shoes or trainers, (no clogs or boots). Colourful clothes (no woollen shawls). University students and some black or brown faces.

Musak!

Kids bossing their mothers in the street. Once it would have been described as,"Showing me up like that!"

Cafes! Restaurants!

Supermarket and roads where there was once a railway station, engine sheds and sidings. Some things were the same. Trains (diesel) still rumbled over a renovated Carlisle Bridge. The River Lune still lapped at high tide against St George’s Quay. Inland seagulls occasionally screeched overhead. Customers still mingled and chattered in the new market just like their grandmothers had in the old one.

It wasn’t all change. Some things were better, some worse. Nostalgia could be tinted with rosy colours.

Michael learned, after a couple of days of his visit, that much tangible evidence of his early life in Edward Street had vanished. Worst of all was his inability to find people who had known him, or his family, 50 years ago.

He awoke in the middle of the night in the Castle Hotel and began to think that he might have been better off staying at home. His vivid memories would never change. Back in Lancaster, he seemed to be losing his past rather than regaining it. Nevertheless, during the day, he went round the town taking photographs, did some sketching and began to write down some of what he remembered of his own childhood. He recalled what his family had told him, about their lives in Lancaster, in the decades before the end of the War in 1945. As he wandered around, old associations were revived. Places began to remind him of much he had forgotten.

Old memories were beginning to circulate again in his consciousness.

Michael's father was born in Marton Street, Lancaster, in 1904. He lived, until he married, with his mother and brother, in a tiny terrace house. It was one of a row all condemned as unfit for human habitation.

Michael’s most vivid memory of being there was of something that happened when he was three years old.

The lav was out in the yard, in a shed, shaped like a sentry box. It was shared by six families whose houses all backed onto the yard. Each household had a key.

Michael needed to do 'number twos'. It took him a long time. Somebody banged on the door loudly, three times and a deep, bass voice shouted, "What the bloody hell are you doing in there? Baking a cake?"

Michael wiped his bottom on a bit of newspaper, pulled up his short trousers and tried to turn the key. But he couldn't.

In a tearful voice he said, "I can't open the door."

Bass voice urged him, "Take your key out of the lock and I'll open it from out here. And hurry up! I’m nearly pissing myself!"

Nan’s house used to stand where the new Police Station is now. There was a strong sense of community in that street, intensified by shared sorrows, after the deaths of so many of their loved ones during the First World War.

Margaret, Gordon’s pretty, dark-haired, slim wife, was born in Wales, in 1910, and moved, during the Great Depression, to lively Morecambe, where she was a young teenager, in the place which was a Mecca for the workers on holiday from inland towns. Morecambe holiday providers thrived and many prospered during the Great Depression.

Their son, Michael, was born in 1933, in Thurnham Place, just across the main road from the end of Marton Street. Michael was only two when they moved from there and he could not remember what it was like inside. A slum, the Place had been demolished many years ago.

Michael’s sister, Gwyn, was born in 1935, in Edward Street.

|

| Unchanged Lancaster today |

• Read more about Green Ayre Station from the Lancaster Archaeological and Historical Society

• Information about the history of Lancaster Castle Station

• The Old Town Hall and The Rag and Bone Man paintings by Tom Dodson. Reproduced with permission courtesy of Studio Arts, Lancaster

No comments:

Post a Comment