Gordon could be moody occasionally but he rarely lost his temper. His and Margaret's was a love-match. Sometimes, they disagreed and fell out, Margaret alway found it was difficult to have a real row with Gordon. She might rave, but he would go quiet and sulk. It excited both of them when they rowed, though. After it was over, they usually made love.

Gordon enjoyed sex but didn't get enough of it. Sometimes, when he felt particularly frustrated, he wondered why he'd married. He'd had more of it when he was single. But he kept these thoughts to himself...

Gordon had two alarm clocks by his bedside. The extra one was there in case the first one failed to ring. He dare not be late for work. To ensure being there in time, he had to set out at six every morning. It was a long walk. He carried his lunch box and a rubber cape and leggings, in case it rained. In all seasons, he wore a flat cap when he went to work, one with a check pattern on the top. He was a craftsman so he wore a tie.

It was nearly two miles to where he worked at Williamson's lino factory. Many still called it the Shipyard, although linoleum had been made there for donkey's years. Gordon's long stride meant that he overtook many other workers on his way. He used to set himself a target as he left home, of how many he would pass on his way to Williamson's. Sometimes, he ran the last few hundred yards in order to meet his arbitrary target.

"Why's he running?" a mate who saw him would think, "We're not late?"

Working days, Margaret was always first up, her footsteps light on the stairs. There was the scratching of a match and soon, crackling from the wood, under the coal on the fire. Gordon always laid it the night before. The next thing Michael heard was the sound of his Mam filling the kettle to boil hot-water. Margaret brewed the first cup of tea of the day and made a bowl of hot porridge, to send Gordon off warm to work.

Even at that early hour, you could hear the machinery, in the mill, behind their Edward Street house, humming away. Twice a day, that mill's buzzer would sound, a sort of siren, to warn the workers that they had better hurry or they'd be late. That would mean, without exception, a punishment: a docking of wages, for a few minutes lateness; or a sending home, for a day without pay. Worse still you might get the sack, especially if one of the bosses didn't like you.

Some still paid a knocker-upper to bang on their bedroom windows with his long pole, to make sure they got out of bed promptly. He was a legacy from, not that long previously, when few had watches or clocks or could not tell the time. When Gordon hurt an ankle, playing football,for the works team, he worried even more about being late. He left the house half an hour earlier, every morning, because he could only limp there slowly. He kept that up for six weeks, in agony every day. Thankfully, the ankle mended. But he packed in playing soccer. He couldn't afford to have time-off, if he was injured. It was the same if he felt ill: somehow, he always struggled into work.

The buzer for afternoon work, in the mill up Moor Lane, fascinated the infant Michael. When he heard it, he'd persuade his mother to open the parlour door of their two-up and two-down house. She'd put one of their bent-wood chairs up against the window. She'd place a cushion on the chair and lift Michael on to it. He'd kneel there and watch what happened in the street.

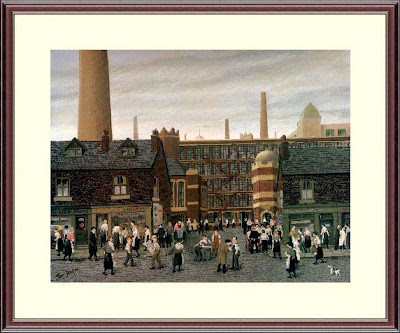

As if by magic, people appeared outside and passed the window. They looked like Lowry's matchstick people. Nearly all wore dark clothing. They shuffled past and headed round the corner of Moor Lane. Some were wearing clogs, which clattered on the pavement, and a young lad would occasionally kick the cobbles of the road and make sparks fly, as the metal on the soles of his clogs smacked against the stones. Latecomers hurried past and finally, there was the odd scampering boy, his face anxious, determined not to be late, for fear of losing precious pence.

After the last one had gone, Mike would call to his mother to lift him down. He had power over her, exercised it mercilessly and she didn't seem to mind. His slightest wish, his every whim was catered for by his Mam. She had to jump to it or he'd moan at her or cry! Gordon thought that she pampered him too much.

After his sister was born, things changed. Quite a bit! Like, when he called to her to lift him off the chair, when all the workers had gone by.

Sometimes, she'd respond, "You'll have to wait a minute, I'm just changing a nappy!" or "I'm feeding the baby!" and finally, "You're big enough and old enough to get down yourself! And don't forget to put the chair back in its right place!"

He liked to kneel on the chair in the parlour at other times. He might look out through the window and look at the horse-and-cart which brought the coal. The coal-man used to put a nose bag on the horse outside theirs. The old horse would have a bit of a rest and a feed while the hefty, grimy, coal-man lifted the hundredweight bags off the cart. He'd prise open the cellar cover, which was let into the pavement, push it out of the way, ease the bags of coal over the hole and coax the fuel out. He'd let it tumble down into the cellar. When he'd finished, there would be coal dust all round the cover. It would not be there for long. It would soon be swept away by Michael's mother, the zealous housewife. The cleanliness of your stretch of stone flags was as important as your personal hygiene. Emblems of pride or shame!

Looking out onto the street was a thing to do when Michael was bored. Something else was ‘playing' an old harmonium which was kept in his bedroom. One of his great-aunts, who lived further down the street, had given it to the Watsons. Everyday, Michael liked to have a go on it. He had to stand up to reach the keys. He gave them a real bashing. He would sing along tunelessly with the discords he was creating.

His mother used to shut the living-room door, to keep most of the noise out. She was glad to have him amusing himself and not needing her to amuse him. Unexpectedly, and in Michael's view, unreasonably, a stop was put to his playing. It was, "You'll wake Gwyn up," or "I'm trying to get Gwyn to sleep." He didn't take a lot of notice but carried on going upstairs and hammering away at the organ whenever he felt like it.

She insisted, so he put on his parts. It was a daily battle which went on for weeks. It was solved when Margaret offered the organ to one of her sisters who lived in Lodge Street. Michael's Uncle Joe came with another man and took it away. Gordon had to hold tight to Michael until they were out of the house. He was kicking and struggling to be free.

"It's all her fault," stormed Michael, pointing at Gwyn lying happily in her pram, "I hate her."

Gwyn smiled and kicked her tiny little legs about. Michael shook a handle as hard as he could making the pram rock. And that made Gwyn gurgle with delight all the more!

"Michael! Behave yourself!" said Margaret.

"Huh!" responded Michael. He fetched his toy rifle and pretended to shoot both of them.

"Michael! I've had about enough! Just you wait ‘til your Dad comes home!"

"Huh!"

|

| Edward Street, Lancaster today |

• Dinner Time at the Mill painting by Tom Dodson. Reproduced with permission courtesy of Studio Arts, Lancaster. All other images © Bill Jervis

No comments:

Post a Comment