Gordon had inadvertently complicated his life and his two very different love affairs had unexpected side effects. The Joyce thing had been very brief but Gordon was fearful that Margaret might hear about it. He had been relieved that there were no immediate repercussions, but his unease increased as the weeks passed. He didn't trust Joyce not to drop him in it.

She had plotted and planned to seduce him. It was a combination of his vanity, her sex appeal and his inclination to cut a dash in front of his friends, that had made him go with her in her car on that night. What a fool he'd been to put so much at risk for so little return!

Thankfully, she had been incapable of hurting his feelings. He was only too eager to put a swift end to the affair. He knew she must have been hurt by the way he had treated her. He knew that he was special to her and always would be. The more he pondered the matter, the more he was convinced that he had not seen the last of Joyce.

With Beth, it was different. From the moment he set eyes on her, Gordon became obsessed with her. He was like an immature, mooning adolescent. The surprising sexual encounter he'd had with her and her friend Lesley in no way diminished his romantic feelings. He'd enjoyed the sex but it was his vision of her that obsessed him. It was his illusion and his delusion that mattered. They were dangerous and threatening to give him trouble.

If he'd been an artist or a writer she would have become his muse. He'd read about Dante and Beatrice and the effect one encounter with her had had on the poet. Gordon thought that his feelings for Beth were like those Dante had had for Beatrice. Gordon was good at deceiving himself and conveniently forgot that Dante had never shagged his beloved.

A month had gone by since his overnight stay at Halton with the two women. Beth had not been at any of the Friday night meetings, so he asked Jack about her.

"Don't really know," said Jack. "I see her occasionally at work. She always says she hopes to be at the next meeting. Things crop up. It's a busy time for all of us at my school. I expect it's the same at her place.

"Is it something important you want to see her about? I could take a message for you."

Gordon looked closely at Jack. Why had he said that? Did he suspect there was something between them? Jack waited for an answer, no gleam in his eye, no eagerness, no suggestion that he was hoping to have a part in a conspiracy.

Gordon responded in a matter of fact tone of voice. "No, that's all right Jack. I was just wondering what had happened to her, that's all. She seemed to enjoy herself with us. It was she who had the idea about us having the booze every week. Remember? By the way, it's my turn to bring some wine next, isn't it?"

He wondered what to do. He had some quite ingenious ideas, but he needed one that was practical. He might be feeling and wanting to act like a sixteen year-old, but his situation was different from that of a callow youth. He had no peers in whom he could confide and from whom to seek advice. There were no spotty-faced cronies who might sympathise with him and his ridiculous dilemma. He was no frustrated teenager able to behave badly at home and work his feelings out on someone else.

No, he had to think this through in a truly adult fashion.

"Adult?" he thought to himself. "I'm not behaving like one!"

He considered buying a bicycle. It would enable him to reconnoitre the area where Beth lived and he might be able to engineer an accidental encounter. He could go there on the off-chance of seeing her. It was a stupid idea, he thought. He couldn't afford a bicycle. If he did buy one, Michael would have to have one too.

The evenings were dark in December. It was a long walk to Halton. He could find no excuse to be out of the house or be home late from work. There were no elections pending and no chance to say he was going out leafleting. If he said he was going to see the Matthews, Margaret might compare notes with Sheila.

Writing her a letter, and sending it via Jack, he had already ruled out. Jack did not seem to be the man for that sort of thing. Too straight! Too high-principled! He would probably give his friend a dressing-down if he suspected any hanky-panky. Jack liked Margaret. Gordon assumed he would object to being asked to play any part in her betrayal. If he decided to address a letter to her at school, it could fall into the wrong hands. It might not be a good idea to put anything down in writing. His written words could be used against him at a later date. If they fell out, Beth might send any letter he'd written back to Margaret.

"So much for my starry-eyed view of my perfect female!" he thought. "Contemplating that she might one day try to drop me in it! How could I think such a thing? Well..!"

He sometimes read old copies of the News of the World which blokes left lying around at work. He'd read about ex-girl friends in juicy divorce cases using love-letters in court when it suited them.

Nevertheless, he went on to thinking about writing to her. What about the briefest of notes, suggesting a meeting? It didn't have to be in his handwriting or signed. He could go to Jack's discussion group early and type one on Jack's typewriter. If only he had her home address! But surely, he could risk posting something like that to her school.

He decided that this plan had possibilities. After lengthy prevarication, he decided that he would send a typewritten note.

Unless Beth responded to his letter and put him off seeing her, he would need an excuse to be out of the house one Saturday afternoon.

Then he thought of a complicated plan. What he would do was tell Margaret that he was going to watch Preston North End with some lads from work. North End were doing well in the First Division that season and were one of the best teams in the land. Buses went from Lancaster to Deepdale every other Saturday. It being winter, kick-off would be at two o'clock. It meant the buses would be leaving Lancaster at half-past twelve. He'd tell Margaret he was going to the next match straight after work.

He thought long and hard about it. It seemed to be foolproof. He decided to act.

"It'll only be the once, love," he said to his wife. "They're having such a good season. I'd love to see them. The lads are always talking about some great players, like Mutch and Beattie and Shankly. Okay?"

Margaret agreed that he could go. After all, she'd had her weekend in Barrow. Fair was fair!

On the Friday, he typed his note, before anyone else arrived at Jack's. It read, "Urgent I see you next Saturday. I'll be in the Greyhound Hotel at one o'clock." He didn't sign it. He typed her name and the school address and fixed a stamp on an envelope. He walked the long way home and posted it at Oxcliffe Corner.

The following Friday, there was no Beth at the meeting. Jack gave him no message from her. He was glad she'd said nothing to Jack about the letter which she must have received. He assumed she hadn't spoken to his friend. Jack would surely have mentioned it.

Saturday morning, came. After work, he walked as far as Damside Street then headed for Halton, via Skerton Bridge, Main Street and Halton Road. He hoped he wouldn't meet the Fascist thugs who'd attacked him the last time he was there!

He grinned to himself. "I won't have a woman to protect me like last time."

The further he walked, the more excited he felt, at the prospect of seeing Beth again. He resisted the idea of skipping along. Like a film-star in a musical! He made up some doggerel, which fitted a popular tune, and sang the verse softly to himself.

Ring those bells!

Bang that drum!

I'm in love,

Here I come!

Of course there was always the chance that she wouldn't turn up. She might have decided that she did not want to see him. Perhaps she hadn't realised the note was from him. Perhaps she had something better to do. He'd soon find out. He was nearly there.

It was a quarter to one when he arrived at the pub. He went into the lounge and ordered himself a pint of bitter. There were only three others in there, all leaning on the bar. He went and found a seat in a corner near the open fire. He could watch the main entrance from where he sat. He sipped his beer and waited. The minutes passed and they seemed like hours.

Then he saw her coming towards the entrance. She was on her own. She was wearing a long black coat. Her red hair stood out vividly against it. She was smoking a cigarette.

She came straight into the lounge. The landlord greeted her, "Hello stranger! How's Beth today?"

"I'm fine, thank you Mr. Stamp."

She looked around and saw Gordon in his corner. She went over to him and sat down opposite. She looked straight at him, loosened the collar of her coat, blew a cloud of smoke over his head and said, "Hello Gordon! Nice to see you. I assumed the note was from you."

"Hello Beth! Thanks for coming. What can I get you to drink?" There was a studied casualness about his manner and speech.

"My usual please, a glass of red wine!"

The lounge was starting to fill up. There were a number of locals but there was passing trade too. Several cars were parked outside. For a while, they could talk quietly and not be overheard because no-one sat too near them. To start with it was all about school, Williamson's, family and Lesley. She explained about how difficult it had been for her to be at any of the recent meetings. He was going nowhere with the chat. Quite abruptly, he cut across all the small talk and whispered to her urgently.

"I've really been wanting to see you again. I've been thinking about you a lot."

Her eyes sparkled mischievously. "Have you Gordon? And why's that?"

"You must know why!"

She grinned at him. "No! Go on, tell me!" So he did. Silly, stupid sod! He poured his heart out to her. She grinned at him even more. "Oh, come on Gordon," she whispered back, "you're a married man. Why would you be wanting to see a girl like me regularly? There'd be no future in it."

He told her he was crazy about her, but it didn't have the effect he'd hoped for. She made it obvious that she didn't like what he'd said. She told him all about how she didn't want any kind of tie. Freedom was the thing!

She and Lesley had an agreement. No regular boy friends. Nothing serious. "Your friend Jack understands," she told Gordon. "Ask him! Get him to lend you one of his books on free love! He's an expert. He has the right attitude."

"You mean that -- you and Jack? You've been with him, like with me?"

She smiled sweetly and repeated, "Ask Jack!"

She offered her hand to him to shake. She leaned forward towards him across the table. "Now come along Gordon. Don't sulk! Be a good boy! Cheer up! We can be good friends can't we? We're all comrades on the same side, aren't we?"

Quite miserable because of her attitude towards him and because of what she'd said, Gordon made one last effort. "But what about us? Have you felt nothing special about me?"

Beth was becoming annoyed. "Listen, Gordon! I will not be a romantic, fantasy figure for you or anyone. I am not a significant character in the story which is your life. I am the principle character in my own story. I decide the part other people have in it.

"You're losing the plot!" she continued. "Accept being my friend or forget me altogether! Don't act like a little boy who's had an ice-cream snatched away from him!"

Gordon took her hand but didn't say anything. He kept on staring at her in disbelief. How was it possible for him to feel so much for her and she so little for him?

She stubbed her cigarette out in an ashtray and finished her wine. "Now I have to go. Lesley and I are going to do our Christmas shopping. I can't stay here any longer. I'll see you again soon at one of the meetings. Thanks for the drink." She stood and fastened the collar of her coat again."See you at Jack's after Christmas!" And off she went.

"Cheerio Beth!" the landlord called after her. "Mind what you get up to!"

"Bye, Mr. Stamp," she replied.

Gordon sat there for a few seconds, then he left his half-empty glass behind and hurried after her. He caught up with her and grasped her arm. She turned round looking a bit startled. Before she or he could say anything, there was a voice from behind them. Someone had just got out of a car and was calling to him.

"Gordon! Hello Gordon! You're a long way from home!"

Poor Gordon -- he could not believe his bad luck. It was Joyce, speaking to him. She walked towards the pub entrance, paused there and waved to him. She had a companion. She was with a big fat middle-aged man her affluent boy friend, Joe Treacle.

Gordon was dumbfounded. He did not return her greeting right away. She waved to him again. "Be seeing you, Gordon! Tell Margaret I'll be calling on her soon. Give her my love!"

She went inside the building before Gordon could respond. Beth tugged herself free from his grasp and carried on going away from him.

"Not your lucky day is it, love?" she called back. She had a big, broad smile on her face. He stood there alone feeling upset, guilty and apprehensive. He decided to let Beth go. What was the point?

"Serves me right! I've been a bloody fool. Again!"

He had to kill time before he was expected home. The bus from Preston wouldn't be back in town until around five o'clock. Margaret would not be expecting him back home for ages. He decided to go and watch Lancaster City playing soccer on the Giant Axe Field.

A couple of lads who he used to play soccer with were having a game for Lancaster. "I was as good as either of them," he thought, miserably. "It could have been me playing if I hadn't packed it in!"

He decided he'd watch the Lancashire Combination match. After that, he'd go up town and see his mother for a while. On his way home, he'd call at a newsagents and buy the soccer edition of the Lancashire Evening Post. There'd be the result and a review of the match at Deepdale. He'd be able to tell his wife about the game he was supposed to have been at.

As he walked away from Halton, he tried to find reasons for Beth's behaviour. It occurred to him that she was a female equivalent of his brother Frank. Frank was determined to keep his freedom and had had numerous girl friends. His brother wasn't that much younger than Gordon. But Frank had been enjoying himself with the other sex for years. It was easy for him being single. All the years that Gordon had been stuck in his marriage Frank had been fancy free.

"I'm being unfair!" he thought. "I'm not stuck in a marriage. My marriage is fine. Frank hasn't got lovely kids like I have. What would my life be without Michael and Gwyn?"

But the thought persisted. Frank had had all sorts of fun which Gordon had missed. Frank had had more than his share. A man of his age should be settled. It definitely wasn't right him still being on the loose. On the other hand, he didn't do anyone any harm, apart from breaking a few hearts along the way. So good luck to him!

"But as for women over twenty-one having as much freedom as they liked," he thought, " that's not natural! It's all wrong."

These modern women thought they could do anything, he argued to himself, his mind racing. If they had some spare cash, like Joyce, they were irresponsible the way they carried on. Career women like Beth and Leslie thought they could please themselves. They didn't care what people thought about their behaviour.

They'd be wanting equal pay next! It was plainly ridiculous! Perhaps the trouble had started when they won the vote. It wasn't right for women to be carrying on like they were. It was not respectable.

Beth's summary rejection of him had made him disgruntled. He was feeling all bitter and twisted. He temporarily forgot his own eagerness to be with freedom-loving women twice during the last twelve months. Thinking all round the subject he came to a definite conclusion. Men were made differently from women weren't they? It was only natural to want a bit on the side. Wasn't it?

If he'd been able to discuss the matter with Jack, he might have straightened him out. Jack would have tried to insist that he think and behave more rationally. Gordon was more than a little bit confused. Confused by his own ambivalence. Confused by what some women seemed to be up to these days! Feelings affected and contorted his thinking.

The next thing he did was try to cheer himself up, by putting Beth down, right down, alongside Joyce. Yes, even as low as Joyce!

Two bits of slag, that's what they were! One was a Durex-carrying rat bag! The other was a raving lunatic dyke.

He knew that if he'd been able to tell the blokes at work what had happened to him his mates would all agree.

Discover a marvellous trip back to Lancaster of the past by author Bill Jervis, which we plan to release in weekly segments. Although the story is set in Lancaster the family and most of the characters within are entirely fictitious -- but this story does chart a way of life largely lost and which many Lancastrians may recall with equal horror and affection...

Monday, 29 October 2012

Chapter 49: Beth Blues

Labels:

Greyhound Hotel,

Halton,

Lancaster City,

Preston North End

Thursday, 25 October 2012

Chapter 48: Morecambe Illuminations

Earlier in the year, Nan had taken Michael to see Walt Disney's Snow White And The Seven Dwarfs.

It was being shown at the Odeon cinema, on King Street, in Lancaster.

The cinema was a new exciting building, a symbol of the progress and

improvements which were very slowly transforming some few working-class

lives. The architecture was jazz moderne, (art deco). It was one of many similar film palaces being built all over the country.

Inside, there were thick carpets, a spacious foyer and what looked like expensive decorations. There were comfortable couches for those who had bought their tickets and were waiting for friends or for a performance to start. The discreet electric light fittings and wall coverings were well designed. The overall effect was intended to sooth and welcome. It was the most luxurious place that Michael had ever been to.

Inside the cinema itself was a vast, cavernous space with plush seats, set in tiered rows downstairs and upstairs. The seats were tip-ups with plenty of room for your legs and soft and comfortable. There was a stage with a high and wide curtain onto which soft lighting was projected with subtly changing colours. There must have been room in there for thousands, Michael thought. It was so capacious. It was the biggest place that Michael had ever been in.

Nan and he sat in the cheap seats, just three rows from the front. They were set well back from the screen so Nan didn't have to tilt her neck back much. Occupants of the cheap seats in some cinemas came out with stiff and aching necks. When the film started, Michael stood up some of the time. He hid behind the back of the seat in front, whenever the evil step-mother appeared on the screen.

Before they went to the cinema, Nan had tried to describe to him what a film was, but the experience amazed him. Its impact exceeded his wildest dreams. It was the most astounding thing that had ever happened to him. He'd always believed in magic, ever since he'd heard his first nursery rhymes, and read about Merlin and Aladdin and his lamp and many other similar stories. But for Michael this was reality exceeding imagination. It was marvellous, exciting and frightening. It did all sorts of things to him.

The story lived with him, long after seeing the film. Mam bought him colouring books with outline figures of Snow White and the Dwarfs. They had table mats, which Dad brought from work, with the cartoon figures on them. Michael learned the songs and sang them with Dad when he was taken up to bed each evening. "Heigh Ho! Heigh Ho! It's off to sleep we go!" He and Rob acted the story and made up new adventures for the characters.

Michael found it difficult to imagine anything that could give him more pleasure than his first visit to a cinema.

But Gordon had a real treat in mind for the kids. Michael was even more enthralled by what they did one weekend. It was a Saturday afternoon when Michael's Dad said, "After tea, we'll go down to Morecambe and see the Illuminations. I've heard that they've got Snow White in Happy Mount Park. We'll walk to Torrisholme and catch a Circular bus. That will take us as far as the Promenade, at Bare. We can walk to the Park from there. Afterwards, we'll go on a bus from the Park, all the way to the West End. At the Battery, we'll catch a bus back home."

Margaret said, "Why can't we catch a bus on Scale Hall Lane? Why do we have to walk all the way to Torrisholme? We'll be tired before we see the lights."

"Because all the Ribble buses from Lancaster will be packed. There will be loads of people from Lancaster trying to go to Morecambe. The buses will go sailing past us. We could wait there for ages. But Torrisholme Square's where the green buses start from. We'll catch one there quite easily. No problem!"

"All right then!" agreed Margaret. "But no racing! None of that fast walking! We'll take it easy."

"Okay!" said Gordon.

Michael was jubilant "Hurrah! Hurrah! Gwyn, we're going to have a good adventure." "Hurrah! No problem!" said Gwyn.

It was late October. It was already dark when they set-off from Sefton Drive to walk to Torrisholme. They took an electric torch because there was no moon and there was no street lighting down their road.

Gwyn was quite a good walker now and did not tire until half way up Cross Hill. Dad carried her from there to Torrisholme Square. On their way three double-decker Ribble buses passed them.

As they sped past Gordon said, "Look, I told you so. They're packed. All the seats are taken. Look at all the people standing!"

One of the green-and-cream Morecambe and Heysham Corporation buses had just arrived in the Square. Gordon was proved right. There wasn't much of a queue.

Michael didn't want to go on the top deck so they went downstairs. The bus-conductor rang his bell twice, which told the driver it was time to go. Then he came round for the fares.

He had a machine with a handle hanging from his neck. He selected the right price on his machine's dial and turned the handle. The machine printed the tickets. There was a whirring noise. The tickets came out of a slit in the front of his machine.

"Can I have them, please?" asked Michael. Dad handed over the roll of five tickets. The bus-conductor gave Gordon his change. He kept his money in a leather bag, which was also hung from his neck.

"Fares please!" called the conductor as he moved along the bus. People would call out, "Next stop please!" There was one ping on the bell and the bus slowed to a stop. He gave it two pings when he wanted it to go. Michael thought it must be good to be in control of a bus like that. Nobody else was allowed to ring the bell.

"Ping! Ping! Ping!" sang Michael and Gwyn as they skipped ahead of their parents on their way to the Park. Everywhere it was magic. There hundreds, thousands, it seemed like millions of coloured bulbs strung up between the lamp posts. They were on the sides of buildings and attached on high to cables from oneside of the wide Promenade to the other. The lights extended as far back as the eyes could see towards the centre of Morecambe and beyond.

"Miles and miles of them!" Michael shouted.

The darkness was transformed into Wonderland. Anticipating crowds were making for the Park and you could feel the excitement in the air. There was a long queue when they arrived at the park. It was quite a cool night but they were wrapped up warm. "Michael, hold your Dad's hand! Gwyn hold mine! We don't want you getting lost. We'd never find you again in this crowd."

Michael clutched his Dad's hand tightly. He didn't want to be lost in the dark.

The queue shuffled forward slowly. At last, they reached the gates. Dad bought four tickets and they followed other families down the main path.

At Sunday School they'd talked about the Gates of Paradise. Michael thought they must have meant something like the illuminated Happy Mount Park because going through the iron gates and into the park was like entering another world.

You had to keep to the paths as you went round so everybody had a good view. There was no pushing or shoving and no loud shouts. Just the loud murmurs and mutterings of astonishment. Hordes of children were astounded by the ingenuity and realism of the moving tableaux. It was like a dream place. The delighted adults were like children themselves taking a naive pleasure in all that attracted their eyes.

Michael went wild with excitement when he saw Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. "Look Gwyn! Just like the film! The one I saw with Nan."

There was a train you could have a ride on. It was all lit up. There were monsters with flashing eyes and nodding heads. There was every conceivable combination of bright bulbs illuminating the gorgeous flower-beds. From behind shrubs and trees little mythical creatures suddenly appeared. Lights flickered dimly in a grotto. Magic lanterns swung overhead in a gentle breeze.

There were fairies and elves and huge toadstools with weird creatures sitting on them. Gwyn wasn't too keen on the dragon, which roared and puffed out green smoke from its jaws.

In different areas of the park, music filled the air with tunes appropriate to the nearby exhibits. Michael's favourites were the models of the Seven Dwarfs. They looked so real. Michael was sure that it was them really singing the tunes from the film.

They were in the park ever such a long time. There was no question of being bored. However, it was becoming cooler. Gordon said, "Come on, we haven't finished yet. We'll go for the bus. There'll be lots to see on the Prom."

They made their way to the exit. There was a long queue of people waiting for the buses. It moved quickly. Everything was well-organised. There were four double-deckers filling up just outside the gates and four more across the road waiting to cross into a parking space as the full buses moved away. There must have been a bus leaving every two minutes.

"We'll see a lot more from the top deck," Margaret declared and Michael was persuaded to go up the stairs. They were lucky, because the front seats were empty. They were going to have a perfect view.

"Ping! Ping!" went the bell and the bus moved off. Michael forgot all about being dizzy. There were dozens of other kids on the bus with their parents and they were all pointing at whatever took their eyes. They called out to each other hardly able to contain their excitement. Michael recognised a big kid from school but they didn't speak to each other.

The further the bus went: past the Broadway, Headway and Grand hotels, the new Town Hall, the Tower Ballroom and Cinema, the more lights there were to be seen. Most boarding houses were competing with each other and had their own displays. The nearer they came to the Central Pier and Euston Road the greater the profusion of colour. What a stupendous spectacle! Margaret pointed down Queen Street. The street was jam-packed with revellers.

"Look Gordon, you can just see Joyce's pub. Down there on the right. Did you see it?"

"I think so," replied Gordon.

Michael tugged on his Dad's sleeve. "Look Dad! Look the other way! The Clock Tower, it looks lovely all lit up!"

The Promenade Gardens, the shops, the pubs, the amusement arcades and the Winter Gardens all were illuminated and all were a feast for the eyes. There were no vulgar displays. It was a class act. The overall design was splendid.

Morecambe's new pride, a fine example of municipal planning, came next. There were superb examples of art-deco architecture: the marvellous Midland Hotel, Woolworths, Littlewoods, the Super Swimming Stadium, the Empire and Arcadian complex were all passed. There was plenty of time to see everything because the traffic was so dense and moved very slowly. Next came the lights on the Midland Promenade Station, the Empire and Arcadian theatres, the cafes and the arcade.

There was so much traffic now that the bus was often at a standstill. The conductor did not need to ping his bell, passengers jumped on and off the bus when it suited them. Michael was glad that it was a slow journey because he was able to absorb everything. It was like going into a tunnel of majestic splendour. The coloured lights shone prettily everywhere, all the way past the new helter-skelter Cyclone, the Dodgems the amusement arcades, the Whitehall cinema and the West End Pier.

Michael's asked his Dad, "I think we must be in Heaven Dad. Do you think Heaven is like this?"

"Could be!" Gordon laughed.

Thinking about Heaven made him think about Granddad Henry and he suddenly felt sad. A shiver went down his spine. There was a hint of bitterness even in an experience as sweet as this. He hoped his Granddad was happy in his heaven. Then the sad thought went away as quickly as it had come.

The Clarendon Hotel was amazing. It had so many lights you could hardly see the building. "I bet they'll win the prize for the best lit hotel," Margaret said.

The West End Pier's illuminations were reflected in the calm water of the tide which had crept across the Bay and was now lapping against the sea wall.

"Ping!" went the bell. "Battery! Terminus!" called the bus-conductor. Dismayed, the children realised they had reached the end of the promenade. They had to leave the bus. They mingled with the crowds on the pavement. Even here, well away from the crammed central part of the Promenade, you could hardly move. There were so many people out for the evening.

There were locals, day-trippers and holiday-makers. All were enjoying lovely Morecambe, with its proud and justifiable boast of being a place where health abounded and beauty surrounded. "Can't we go back again Dad, when the bus turns round? I want to see it all again" "No, not tonight son. It's long past your bedtime. There'll always be another time."

But there wasn't! There was never another time like that for the Watsons.

War would be declared before the next Morecambe Illuminations. It would be another ten years before the lights were switched on again. By that time Michael and Gwyn's childhood would be over. Things would never be the same. Never! Not ever again! The magical moments would be lost. But always remembered by those who had experienced them.

Inside, there were thick carpets, a spacious foyer and what looked like expensive decorations. There were comfortable couches for those who had bought their tickets and were waiting for friends or for a performance to start. The discreet electric light fittings and wall coverings were well designed. The overall effect was intended to sooth and welcome. It was the most luxurious place that Michael had ever been to.

Inside the cinema itself was a vast, cavernous space with plush seats, set in tiered rows downstairs and upstairs. The seats were tip-ups with plenty of room for your legs and soft and comfortable. There was a stage with a high and wide curtain onto which soft lighting was projected with subtly changing colours. There must have been room in there for thousands, Michael thought. It was so capacious. It was the biggest place that Michael had ever been in.

Nan and he sat in the cheap seats, just three rows from the front. They were set well back from the screen so Nan didn't have to tilt her neck back much. Occupants of the cheap seats in some cinemas came out with stiff and aching necks. When the film started, Michael stood up some of the time. He hid behind the back of the seat in front, whenever the evil step-mother appeared on the screen.

Before they went to the cinema, Nan had tried to describe to him what a film was, but the experience amazed him. Its impact exceeded his wildest dreams. It was the most astounding thing that had ever happened to him. He'd always believed in magic, ever since he'd heard his first nursery rhymes, and read about Merlin and Aladdin and his lamp and many other similar stories. But for Michael this was reality exceeding imagination. It was marvellous, exciting and frightening. It did all sorts of things to him.

The story lived with him, long after seeing the film. Mam bought him colouring books with outline figures of Snow White and the Dwarfs. They had table mats, which Dad brought from work, with the cartoon figures on them. Michael learned the songs and sang them with Dad when he was taken up to bed each evening. "Heigh Ho! Heigh Ho! It's off to sleep we go!" He and Rob acted the story and made up new adventures for the characters.

Michael found it difficult to imagine anything that could give him more pleasure than his first visit to a cinema.

But Gordon had a real treat in mind for the kids. Michael was even more enthralled by what they did one weekend. It was a Saturday afternoon when Michael's Dad said, "After tea, we'll go down to Morecambe and see the Illuminations. I've heard that they've got Snow White in Happy Mount Park. We'll walk to Torrisholme and catch a Circular bus. That will take us as far as the Promenade, at Bare. We can walk to the Park from there. Afterwards, we'll go on a bus from the Park, all the way to the West End. At the Battery, we'll catch a bus back home."

Margaret said, "Why can't we catch a bus on Scale Hall Lane? Why do we have to walk all the way to Torrisholme? We'll be tired before we see the lights."

"Because all the Ribble buses from Lancaster will be packed. There will be loads of people from Lancaster trying to go to Morecambe. The buses will go sailing past us. We could wait there for ages. But Torrisholme Square's where the green buses start from. We'll catch one there quite easily. No problem!"

"All right then!" agreed Margaret. "But no racing! None of that fast walking! We'll take it easy."

"Okay!" said Gordon.

Michael was jubilant "Hurrah! Hurrah! Gwyn, we're going to have a good adventure." "Hurrah! No problem!" said Gwyn.

It was late October. It was already dark when they set-off from Sefton Drive to walk to Torrisholme. They took an electric torch because there was no moon and there was no street lighting down their road.

Gwyn was quite a good walker now and did not tire until half way up Cross Hill. Dad carried her from there to Torrisholme Square. On their way three double-decker Ribble buses passed them.

As they sped past Gordon said, "Look, I told you so. They're packed. All the seats are taken. Look at all the people standing!"

One of the green-and-cream Morecambe and Heysham Corporation buses had just arrived in the Square. Gordon was proved right. There wasn't much of a queue.

Michael didn't want to go on the top deck so they went downstairs. The bus-conductor rang his bell twice, which told the driver it was time to go. Then he came round for the fares.

He had a machine with a handle hanging from his neck. He selected the right price on his machine's dial and turned the handle. The machine printed the tickets. There was a whirring noise. The tickets came out of a slit in the front of his machine.

"Can I have them, please?" asked Michael. Dad handed over the roll of five tickets. The bus-conductor gave Gordon his change. He kept his money in a leather bag, which was also hung from his neck.

"Fares please!" called the conductor as he moved along the bus. People would call out, "Next stop please!" There was one ping on the bell and the bus slowed to a stop. He gave it two pings when he wanted it to go. Michael thought it must be good to be in control of a bus like that. Nobody else was allowed to ring the bell.

"Ping! Ping! Ping!" sang Michael and Gwyn as they skipped ahead of their parents on their way to the Park. Everywhere it was magic. There hundreds, thousands, it seemed like millions of coloured bulbs strung up between the lamp posts. They were on the sides of buildings and attached on high to cables from oneside of the wide Promenade to the other. The lights extended as far back as the eyes could see towards the centre of Morecambe and beyond.

"Miles and miles of them!" Michael shouted.

The darkness was transformed into Wonderland. Anticipating crowds were making for the Park and you could feel the excitement in the air. There was a long queue when they arrived at the park. It was quite a cool night but they were wrapped up warm. "Michael, hold your Dad's hand! Gwyn hold mine! We don't want you getting lost. We'd never find you again in this crowd."

Michael clutched his Dad's hand tightly. He didn't want to be lost in the dark.

The queue shuffled forward slowly. At last, they reached the gates. Dad bought four tickets and they followed other families down the main path.

At Sunday School they'd talked about the Gates of Paradise. Michael thought they must have meant something like the illuminated Happy Mount Park because going through the iron gates and into the park was like entering another world.

You had to keep to the paths as you went round so everybody had a good view. There was no pushing or shoving and no loud shouts. Just the loud murmurs and mutterings of astonishment. Hordes of children were astounded by the ingenuity and realism of the moving tableaux. It was like a dream place. The delighted adults were like children themselves taking a naive pleasure in all that attracted their eyes.

Michael went wild with excitement when he saw Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. "Look Gwyn! Just like the film! The one I saw with Nan."

There was a train you could have a ride on. It was all lit up. There were monsters with flashing eyes and nodding heads. There was every conceivable combination of bright bulbs illuminating the gorgeous flower-beds. From behind shrubs and trees little mythical creatures suddenly appeared. Lights flickered dimly in a grotto. Magic lanterns swung overhead in a gentle breeze.

There were fairies and elves and huge toadstools with weird creatures sitting on them. Gwyn wasn't too keen on the dragon, which roared and puffed out green smoke from its jaws.

In different areas of the park, music filled the air with tunes appropriate to the nearby exhibits. Michael's favourites were the models of the Seven Dwarfs. They looked so real. Michael was sure that it was them really singing the tunes from the film.

They were in the park ever such a long time. There was no question of being bored. However, it was becoming cooler. Gordon said, "Come on, we haven't finished yet. We'll go for the bus. There'll be lots to see on the Prom."

They made their way to the exit. There was a long queue of people waiting for the buses. It moved quickly. Everything was well-organised. There were four double-deckers filling up just outside the gates and four more across the road waiting to cross into a parking space as the full buses moved away. There must have been a bus leaving every two minutes.

"We'll see a lot more from the top deck," Margaret declared and Michael was persuaded to go up the stairs. They were lucky, because the front seats were empty. They were going to have a perfect view.

"Ping! Ping!" went the bell and the bus moved off. Michael forgot all about being dizzy. There were dozens of other kids on the bus with their parents and they were all pointing at whatever took their eyes. They called out to each other hardly able to contain their excitement. Michael recognised a big kid from school but they didn't speak to each other.

The further the bus went: past the Broadway, Headway and Grand hotels, the new Town Hall, the Tower Ballroom and Cinema, the more lights there were to be seen. Most boarding houses were competing with each other and had their own displays. The nearer they came to the Central Pier and Euston Road the greater the profusion of colour. What a stupendous spectacle! Margaret pointed down Queen Street. The street was jam-packed with revellers.

"Look Gordon, you can just see Joyce's pub. Down there on the right. Did you see it?"

"I think so," replied Gordon.

Michael tugged on his Dad's sleeve. "Look Dad! Look the other way! The Clock Tower, it looks lovely all lit up!"

The Promenade Gardens, the shops, the pubs, the amusement arcades and the Winter Gardens all were illuminated and all were a feast for the eyes. There were no vulgar displays. It was a class act. The overall design was splendid.

Morecambe's new pride, a fine example of municipal planning, came next. There were superb examples of art-deco architecture: the marvellous Midland Hotel, Woolworths, Littlewoods, the Super Swimming Stadium, the Empire and Arcadian complex were all passed. There was plenty of time to see everything because the traffic was so dense and moved very slowly. Next came the lights on the Midland Promenade Station, the Empire and Arcadian theatres, the cafes and the arcade.

There was so much traffic now that the bus was often at a standstill. The conductor did not need to ping his bell, passengers jumped on and off the bus when it suited them. Michael was glad that it was a slow journey because he was able to absorb everything. It was like going into a tunnel of majestic splendour. The coloured lights shone prettily everywhere, all the way past the new helter-skelter Cyclone, the Dodgems the amusement arcades, the Whitehall cinema and the West End Pier.

Michael's asked his Dad, "I think we must be in Heaven Dad. Do you think Heaven is like this?"

"Could be!" Gordon laughed.

Thinking about Heaven made him think about Granddad Henry and he suddenly felt sad. A shiver went down his spine. There was a hint of bitterness even in an experience as sweet as this. He hoped his Granddad was happy in his heaven. Then the sad thought went away as quickly as it had come.

The Clarendon Hotel was amazing. It had so many lights you could hardly see the building. "I bet they'll win the prize for the best lit hotel," Margaret said.

The West End Pier's illuminations were reflected in the calm water of the tide which had crept across the Bay and was now lapping against the sea wall.

"Ping!" went the bell. "Battery! Terminus!" called the bus-conductor. Dismayed, the children realised they had reached the end of the promenade. They had to leave the bus. They mingled with the crowds on the pavement. Even here, well away from the crammed central part of the Promenade, you could hardly move. There were so many people out for the evening.

There were locals, day-trippers and holiday-makers. All were enjoying lovely Morecambe, with its proud and justifiable boast of being a place where health abounded and beauty surrounded. "Can't we go back again Dad, when the bus turns round? I want to see it all again" "No, not tonight son. It's long past your bedtime. There'll always be another time."

But there wasn't! There was never another time like that for the Watsons.

War would be declared before the next Morecambe Illuminations. It would be another ten years before the lights were switched on again. By that time Michael and Gwyn's childhood would be over. Things would never be the same. Never! Not ever again! The magical moments would be lost. But always remembered by those who had experienced them.

|

| Image via HistoricImages.co.uk |

Monday, 22 October 2012

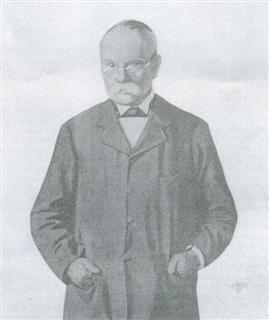

Chapter 47: A Good Man

War had left Gordon's stepfather Henry weakened and never really

well. He'd always had breathing problems because of the gassing he'd had

in the trenches. But Henry believed that he was a lucky man. So many of

his comrades had died in 1915.

He lay in the bed upstairs. It was the same one that Eli and Nan had once shared. The bed took up most of the room. It was a brass bed with a flock mattress. Under the bed was a po.

On the wall, above Henry's head was a verse of poetry, in a wooden picture frame:

Henry's face was very white. His pale blue eyes seemed sightless. It was as though his gaze had turned inwards. His breathing was shallow. The doctor had called and said he was very ill. His heart was packing in. Henry knew he had something seriously wrong with him. He didn't want to fight it. He just wanted to go to sleep. He felt so weary and tired.

When Gordon went to see him, he'd drifted off to sleep.

"He's always been good to me," Gordon thought, looking down at his step-father. He sat by the bedside and thought what a good old boy he was. Not that old, only fifty-four and quite clapped out! Just like a machine that had been badly treated and never functioned well, always likely to break down.

Henry had been a benevolent presence in the house when Gordon and Frank were growing up. He hadn't been allowed to make big decisions for them or punish them when they were in the wrong. Nan did that. They had never done many things together outside the home. He was more like a friendly lodger than a father but Gordon was very fond of him. Everybody liked old Henry. Somehow, he'd always looked old and that was why everybody referred to him as 'old' Henry.

There was no point in sitting there. Gordon contemplated the invalid's blameless life. He thought how lucky he'd been to have had himas a reliable friend. A few more kind thoughts surfaced in his mind. He wished him well. His deep thinking was a kind of praying without a specific formulation.

He went back downstairs to see his mother. Henry had been a good husband to her but she'd never loved him, not how she'd loved Eli. It was over twenty years since Eli had been killed, but you could still feel his presence in the house -- more than you could Henry's. Maybe it was that photograph that was a constant reminder of who had once been the head of the household. Gordon looked up at it now. His father's eyes looked straight back at him.

Nan was quiet. She waited for Gordon to say something.

"I'll come again after work tomorrow," said Gordon.

"All right, son."

"Is there anything I can do for you?"

"Frank's staying in most evenings to keep me company. I've got good neighbours. They're all very helpful in times like this. They'll be popping in and seeing I'm okay. You'd best be going. I'll see you tomorrow."

He kissed his mother on the cheek and left.

Henry was dead within the week. The funeral service was to be at St. Thomas's, situated on the far corner of Marton Street. The burial would be in the cemetery above the town.

Gordon asked for a day off work. Lesser Authority passed the request on to Higher Authority. Gordon was called into the office. "Now Watson, I understand you want a day off to go to a funeral."

"Yes Mr. Jibes."

"It's very inconvenient. We've a lot on at the moment. That roller you're working on needs finishing by Thursday. Whose funeral is it anyway?"

"It's my step-father's."

"I see. Not a close relative then?"

"We were quite close. He helped bring me up."

"Well Watson, if it was your real father it would be different. But I'm going to have to say, No."

Gordon could hardly believe his ears.

"That's a bit hard, Mr. Jibes. My mother's relying on me to be there to support her."

Higher Authority drew a deep breath and frowned. Should he rebuke the man for telling him he was being hard? Should he concede a little? Watson was a steady worker. Never been any real trouble, despite his union activities.

"I'll tell you what Watson. You can have two hours off, provided you come back here afterwards and make the time up with overtime, not overtime pay of course. How about that?"

Gordon responded quietly, "Right Mr. Jibes. Right."

The boss went back to his paperwork. Gordon left the office. Outside, he gave vent to his pent-up feelings. He hit the wall with his fist and said to himself, "Shit! Shit! Shit!" over and over again. "They call us 'Hands' and that's all we are to them. Just 'Hands', without brains and hearts and feelings!"

His brother, Frank, who worked in a different department, had exactly the same treatment. Before the funeral they compared notes and cursed the bloody firm that didn't know how to treat its employees like human beings.

On the afternoon of the funeral, Frank was outside the main gate of the factory waiting for his brother. They were both in their working clothes. Gordon had left his best suit at his mother's the evening before. On their way through town, they picked up the wreaths they had ordered. There was one for their mother too. Gordon asked Frank, "Do you need any help with the expenses?"

No! Everything was taken care of. The Co-op Insurance would be providing adequate cover. It was strange how everybody managed to save for a funeral. They were reasonably well-off now, but if they'd still been very poor, the insurance would have been kept up to date. A proper funeral was essential. You had to show respect to the dead and more importantly behave respectably. One had to be respectable at all costs!

Between them, Frank and his mother had registered the death and made the other funeral arrangements.

"There'll not be many there and with you two having to go back to work I haven't booked a cafe meal for afterwards," Nan said.

The curtains were drawn across the windows of the house, and it was gloomy inside. The coffin was on a trestle table, taking up most of the downstairs room. Nan was all prepared and in black. Her sons went upstairs to change. They came down. Eli's photograph seemed to watch their every movement.

Gordon was standing by the open door and looking out."The cars are here," he said.

The pall bearers came in and lifted the coffin. They placed it in the funeral car.

There were the three family wreaths, and another from some neighbours who had clubbed together to buy one. All four were placed on top of the coffin. Nan and her sons climbed into the other car. It was only a hundred yards to St. Thomas's.

The local vicar was away. There was a clergyman they'd never seen before waiting for them in the porch. The bell rang from above and it felt like a blow to the heart every time Gordon heard it toll. Frank was crying. Nan was stoical as ever.

There were only ten in the church. They were Nan and the two brothers. Stanfast had allowed one from amongst his work mates to attend. A wartime comrade, too ill to be in employment, had managed to make it on his two sticks. Five female neighbours were there. Margaret had stayed at home to look after the children.

Gordon and Frank had been church-goers when they were children. They were able to sing the familiar hymns, "Abide With Me" and "All Things Bright and Beautiful." Nobody else did, apart from the bloke taking the funeral service. He read the words of the service as quickly as possible. Nobody said anything personal about Henry and the good things he'd done in his life.

The service soon ended. Some there shook hands with the family in the porch. A few words were spoken to Nan. No-one was articulate. The brief words were sincere.

A neighbour said, "He was a good man."

The man on the two sticks croaked, "He was a brave lad."

Another of the neighbours said to Nan, "Keep smiling love."

The coffin was carried out again and placed back in the funeral car. It was time for the journey to the cemetery above the town. It was pouring with rain in the cemetery. They were wet through by the time they reached what was to be Henry's last resting place. Mother and sons huddled together during the committal. The men lowered the coffin into the gaping hole. Dog-collar garbled the necessary words and scurried off. And that was that!

The car took the three of them back to Marton Street. The brothers changed again into their work clothes and hurried back to Williamsons. Gordon said to his brother, "Well Frank, all I can say is, he had a few decent years with mother. It was about the only time in his life that he was properly cared for."

"Yes," agreed Frank. "if ever there was a decent bloke, it was Henry. Never did anybody any harm. Always tried his best. He was a real good sort. Being still at home, I got to know him better than you. He was pure gold."

"Yes," said Gordon, I suppose we've had it dead easy compared with how it was for him and a lot of his generation. Anyway, he's nothing to worry about now."

Back at his bench, Gordon's friend Bill asked, "How did it go, Gordon?"

"Bloody awful!" said Gordon. "Life isn't fair is it? Only fifty-four he was and not much to show for all his hard work and always doing his duty. Look!"

Gordon showed Bill the gold signet ring which he'd put on one of his fingers. "This was his. He wanted me to have it. Frank has his watch and chain. And that's it. That's all he had." "Well Gordon, people who knew him, they'll all have good memories of him," Bill replied. "Maybe that's all that counts at the end of the day. It's more than you can say for a lot of them who have loads of dosh."

When Gordon was at home, late, because of the enforced overtime, Michael was demanding some answers. He knew there was something being hidden from him and that it concerned Granddad Henry. The children had known that he was ill. Margaret had said nothing about his death. As usual, she was anxious to shield them from reality. Michael was so easily upset and Gwyn was too young to understand what had happened.

Gordon decided it was time to tell Michael, to try and make sense of what had happened to Henry. As he could not comprehend it himself he had a real job on his hands.

"You know that things die, Michael?"

Michael was sat on his Dad's lap and could tell it was something serious. Gordon was holding him tight and speaking earnestly in a quiet voice.

"Yes, Dad. You mean like when Jesse kills a bird?"

"Well yes, but people die too you know."

"Like Celia? And when you killed that mouse?"

It wasn't a good start. He tried again.

"You know what you learned at Sunday School about Jesus dying and going to Heaven?"

"You mean when those nasty men tortured him and hammered nails into him. Then they hung him up on a cross."

"Well yes, but after all those horrible things, he went to sleep and was happy in Heaven."

"It's not what Rob thinks. He says Jesus came back as a ghost and he's everywhere, watching us in case we do bad things."

"Not quite like that. But listen, people you know have to die too."

"I know Dad. Like I said, Celia died didn't she? Why did she?"

"She wanted to go to a happier place."

"Where's that?"

"Up in the sky -- somewhere out of sight."

"Can she see us down here? Do you get dizzy up there?"

"She might be able to see us. But listen, I've something important to tell you."

Michael was silent and listened. Gordon took a deep breath and said, "Your Granddad Henry has died. He's gone away to be happy. Do you understand?"

"Does that mean I won't be seeing him again?"

"Yes."

"But I want to! He takes me for walks and tells me good stories."

"That's how you'll have to remember him. He was always a good Granddad to you."

Michael's lip trembled.

"It's not fair. There's always something bad happening. It's not fair. Why didn't you stop him? You know I wouldn't want him to go away."

"It wasn't up to me son. I didn't want him to go."

Michael thought his Dad could do anything he wished, prevent anything he didn't want happening. He climbed down off his knee and went over to his mother and she picked him up for a cuddle.

Michael stared at Gordon accusingly, "It's not fair," he said again. "You should have stopped him. I didn't want him to go away. I want to see him!"

He lay in the bed upstairs. It was the same one that Eli and Nan had once shared. The bed took up most of the room. It was a brass bed with a flock mattress. Under the bed was a po.

On the wall, above Henry's head was a verse of poetry, in a wooden picture frame:

SING YOU A SONG IN THE

-- GARDEN OF LIFE,

IF ONLY YOU GATHER A THISTLE,

SING YOU A SONG AS YOU

TRAVEL ALONG,

AND IF YOU CAN'T SING

WHY! JUST WHISTLE.

-- GARDEN OF LIFE,

IF ONLY YOU GATHER A THISTLE,

SING YOU A SONG AS YOU

TRAVEL ALONG,

AND IF YOU CAN'T SING

WHY! JUST WHISTLE.

Henry's face was very white. His pale blue eyes seemed sightless. It was as though his gaze had turned inwards. His breathing was shallow. The doctor had called and said he was very ill. His heart was packing in. Henry knew he had something seriously wrong with him. He didn't want to fight it. He just wanted to go to sleep. He felt so weary and tired.

When Gordon went to see him, he'd drifted off to sleep.

"He's always been good to me," Gordon thought, looking down at his step-father. He sat by the bedside and thought what a good old boy he was. Not that old, only fifty-four and quite clapped out! Just like a machine that had been badly treated and never functioned well, always likely to break down.

Henry had been a benevolent presence in the house when Gordon and Frank were growing up. He hadn't been allowed to make big decisions for them or punish them when they were in the wrong. Nan did that. They had never done many things together outside the home. He was more like a friendly lodger than a father but Gordon was very fond of him. Everybody liked old Henry. Somehow, he'd always looked old and that was why everybody referred to him as 'old' Henry.

There was no point in sitting there. Gordon contemplated the invalid's blameless life. He thought how lucky he'd been to have had himas a reliable friend. A few more kind thoughts surfaced in his mind. He wished him well. His deep thinking was a kind of praying without a specific formulation.

He went back downstairs to see his mother. Henry had been a good husband to her but she'd never loved him, not how she'd loved Eli. It was over twenty years since Eli had been killed, but you could still feel his presence in the house -- more than you could Henry's. Maybe it was that photograph that was a constant reminder of who had once been the head of the household. Gordon looked up at it now. His father's eyes looked straight back at him.

Nan was quiet. She waited for Gordon to say something.

"I'll come again after work tomorrow," said Gordon.

"All right, son."

"Is there anything I can do for you?"

"Frank's staying in most evenings to keep me company. I've got good neighbours. They're all very helpful in times like this. They'll be popping in and seeing I'm okay. You'd best be going. I'll see you tomorrow."

He kissed his mother on the cheek and left.

Henry was dead within the week. The funeral service was to be at St. Thomas's, situated on the far corner of Marton Street. The burial would be in the cemetery above the town.

Gordon asked for a day off work. Lesser Authority passed the request on to Higher Authority. Gordon was called into the office. "Now Watson, I understand you want a day off to go to a funeral."

"Yes Mr. Jibes."

"It's very inconvenient. We've a lot on at the moment. That roller you're working on needs finishing by Thursday. Whose funeral is it anyway?"

"It's my step-father's."

"I see. Not a close relative then?"

"We were quite close. He helped bring me up."

"Well Watson, if it was your real father it would be different. But I'm going to have to say, No."

Gordon could hardly believe his ears.

"That's a bit hard, Mr. Jibes. My mother's relying on me to be there to support her."

Higher Authority drew a deep breath and frowned. Should he rebuke the man for telling him he was being hard? Should he concede a little? Watson was a steady worker. Never been any real trouble, despite his union activities.

"I'll tell you what Watson. You can have two hours off, provided you come back here afterwards and make the time up with overtime, not overtime pay of course. How about that?"

Gordon responded quietly, "Right Mr. Jibes. Right."

The boss went back to his paperwork. Gordon left the office. Outside, he gave vent to his pent-up feelings. He hit the wall with his fist and said to himself, "Shit! Shit! Shit!" over and over again. "They call us 'Hands' and that's all we are to them. Just 'Hands', without brains and hearts and feelings!"

His brother, Frank, who worked in a different department, had exactly the same treatment. Before the funeral they compared notes and cursed the bloody firm that didn't know how to treat its employees like human beings.

On the afternoon of the funeral, Frank was outside the main gate of the factory waiting for his brother. They were both in their working clothes. Gordon had left his best suit at his mother's the evening before. On their way through town, they picked up the wreaths they had ordered. There was one for their mother too. Gordon asked Frank, "Do you need any help with the expenses?"

No! Everything was taken care of. The Co-op Insurance would be providing adequate cover. It was strange how everybody managed to save for a funeral. They were reasonably well-off now, but if they'd still been very poor, the insurance would have been kept up to date. A proper funeral was essential. You had to show respect to the dead and more importantly behave respectably. One had to be respectable at all costs!

Between them, Frank and his mother had registered the death and made the other funeral arrangements.

"There'll not be many there and with you two having to go back to work I haven't booked a cafe meal for afterwards," Nan said.

The curtains were drawn across the windows of the house, and it was gloomy inside. The coffin was on a trestle table, taking up most of the downstairs room. Nan was all prepared and in black. Her sons went upstairs to change. They came down. Eli's photograph seemed to watch their every movement.

Gordon was standing by the open door and looking out."The cars are here," he said.

The pall bearers came in and lifted the coffin. They placed it in the funeral car.

There were the three family wreaths, and another from some neighbours who had clubbed together to buy one. All four were placed on top of the coffin. Nan and her sons climbed into the other car. It was only a hundred yards to St. Thomas's.

The local vicar was away. There was a clergyman they'd never seen before waiting for them in the porch. The bell rang from above and it felt like a blow to the heart every time Gordon heard it toll. Frank was crying. Nan was stoical as ever.

There were only ten in the church. They were Nan and the two brothers. Stanfast had allowed one from amongst his work mates to attend. A wartime comrade, too ill to be in employment, had managed to make it on his two sticks. Five female neighbours were there. Margaret had stayed at home to look after the children.

Gordon and Frank had been church-goers when they were children. They were able to sing the familiar hymns, "Abide With Me" and "All Things Bright and Beautiful." Nobody else did, apart from the bloke taking the funeral service. He read the words of the service as quickly as possible. Nobody said anything personal about Henry and the good things he'd done in his life.

The service soon ended. Some there shook hands with the family in the porch. A few words were spoken to Nan. No-one was articulate. The brief words were sincere.

A neighbour said, "He was a good man."

The man on the two sticks croaked, "He was a brave lad."

Another of the neighbours said to Nan, "Keep smiling love."

The coffin was carried out again and placed back in the funeral car. It was time for the journey to the cemetery above the town. It was pouring with rain in the cemetery. They were wet through by the time they reached what was to be Henry's last resting place. Mother and sons huddled together during the committal. The men lowered the coffin into the gaping hole. Dog-collar garbled the necessary words and scurried off. And that was that!

The car took the three of them back to Marton Street. The brothers changed again into their work clothes and hurried back to Williamsons. Gordon said to his brother, "Well Frank, all I can say is, he had a few decent years with mother. It was about the only time in his life that he was properly cared for."

"Yes," agreed Frank. "if ever there was a decent bloke, it was Henry. Never did anybody any harm. Always tried his best. He was a real good sort. Being still at home, I got to know him better than you. He was pure gold."

"Yes," said Gordon, I suppose we've had it dead easy compared with how it was for him and a lot of his generation. Anyway, he's nothing to worry about now."

Back at his bench, Gordon's friend Bill asked, "How did it go, Gordon?"

"Bloody awful!" said Gordon. "Life isn't fair is it? Only fifty-four he was and not much to show for all his hard work and always doing his duty. Look!"

Gordon showed Bill the gold signet ring which he'd put on one of his fingers. "This was his. He wanted me to have it. Frank has his watch and chain. And that's it. That's all he had." "Well Gordon, people who knew him, they'll all have good memories of him," Bill replied. "Maybe that's all that counts at the end of the day. It's more than you can say for a lot of them who have loads of dosh."

When Gordon was at home, late, because of the enforced overtime, Michael was demanding some answers. He knew there was something being hidden from him and that it concerned Granddad Henry. The children had known that he was ill. Margaret had said nothing about his death. As usual, she was anxious to shield them from reality. Michael was so easily upset and Gwyn was too young to understand what had happened.

Gordon decided it was time to tell Michael, to try and make sense of what had happened to Henry. As he could not comprehend it himself he had a real job on his hands.

"You know that things die, Michael?"

Michael was sat on his Dad's lap and could tell it was something serious. Gordon was holding him tight and speaking earnestly in a quiet voice.

"Yes, Dad. You mean like when Jesse kills a bird?"

"Well yes, but people die too you know."

"Like Celia? And when you killed that mouse?"

It wasn't a good start. He tried again.

"You know what you learned at Sunday School about Jesus dying and going to Heaven?"

"You mean when those nasty men tortured him and hammered nails into him. Then they hung him up on a cross."

"Well yes, but after all those horrible things, he went to sleep and was happy in Heaven."

"It's not what Rob thinks. He says Jesus came back as a ghost and he's everywhere, watching us in case we do bad things."

"Not quite like that. But listen, people you know have to die too."

"I know Dad. Like I said, Celia died didn't she? Why did she?"

"She wanted to go to a happier place."

"Where's that?"

"Up in the sky -- somewhere out of sight."

"Can she see us down here? Do you get dizzy up there?"

"She might be able to see us. But listen, I've something important to tell you."

Michael was silent and listened. Gordon took a deep breath and said, "Your Granddad Henry has died. He's gone away to be happy. Do you understand?"

"Does that mean I won't be seeing him again?"

"Yes."

"But I want to! He takes me for walks and tells me good stories."

"That's how you'll have to remember him. He was always a good Granddad to you."

Michael's lip trembled.

"It's not fair. There's always something bad happening. It's not fair. Why didn't you stop him? You know I wouldn't want him to go away."

"It wasn't up to me son. I didn't want him to go."

Michael thought his Dad could do anything he wished, prevent anything he didn't want happening. He climbed down off his knee and went over to his mother and she picked him up for a cuddle.

Michael stared at Gordon accusingly, "It's not fair," he said again. "You should have stopped him. I didn't want him to go away. I want to see him!"

Thursday, 18 October 2012

Chapter 46: A Visit to Barrow

|

| • Summer Time painting by Tom Dodson. Reproduced with permission courtesy of Studio Arts, Lancaster |

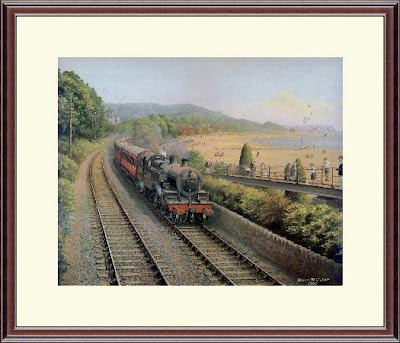

They left Castle Station and its mock-Elizabethan architecture behind and moved off jerkily at first, then more smoothly as the engine got up-steam.

"Mam! Mam! We're crossing Carlisle Bridge," cried Michael, hoping for a bird's eye view of his school. For once, he was enjoying the crossing. Being on a train was different from being on the footbridge and dreading its shaking by a train. He moved over to Gwyn's side and looked back, hoping he'd be able to see St Mary's. He had the merest glimpse of it on the far bank of the Lune. Then they were picking-up speed and heading past Ryelands and Hareruns Estates and the Padfields.

It was a lovely journey, probably one of the best anywhere in the whole wide world. They were close to the sea at Hest Bank and had a view of the Bay and the Pennines on the other side of the water. After the busy railway junction town of Carnforth they went on to Silverdale, as lovely as its busy pretty name. Next, it was Arnside and Grange-over-Sands, which meant they were half-way to Barrow.

It was dusk and there was a spectacular sunset in the west over the Bay. They watched the sun kiss then sink down behind the Lakeland hills. The slowly darkening clouds were decked with a glory of colour – a technicolour spectacle, all the way from the horizon and right over the train. It was as good a sunset over Morecambe Bay as ever inspired the likes of the painter Turner. The tide was in, the sea reflecting the luminous sky, as they went over the water on a long viaduct.

After the sun was long gone and the landscape was quite dark, the clouds over the Bay still had faintly glowing colours, like the embers of an almost defunct fire.

"Mam! Mam! We're sailing over the sea!" chortled little Gwyn. It was true. Enough light remained for them to see the water below. Both she and Michael stood up in amazement. It was quite a distance before they were travelling over dry land again. Michael had not been too worried about the train toppling down into the water but the possibility had crossed his mind.

Margaret pointed out the strings of glittering sparklers which were distant Morecambe's lights. "Look," she said, " those lights! They go for miles along the promenade."

On they steamed to Kents Bank, Ulverston, Dalton, Roose and finally to Barrow. They had completed a magic-makers semi-circle of about fifty miles right round the Bay.

Michael had been mystified when he spotted a lighthouse high on a hill, on the land side. He'd seen a picture in one of his books of one on a rock, out at sea. He thought lighthouses were situated off the coast, to guide ships away from rocks. You couldn't have ships sailing near hills. His Mam couldn't enlighten him. It was the stimulus for another of his weird dreams, with ships going over mountains.

|

| Barrow Central Station before World War 2. Image via the South Lakes Memory Bank |

What made his day was seeing an old railway engine, in a big glass case, outside the railway station."Coo! Look at that, Gwyn!"

Uncle Tom said, "That's old 'Coppernob'. It used to run on the Furness Railway a hundred years ago."

It was beautiful, thought Michael. It looked superb, all shiny copper, brass and steel.

Grandma and Grandpop were ever so pleased to see them. When dark-haired Aunty Julia gave Michael a hug and told him what a big boy he'd become, he thought that she smelled nearly as nice as Aunty Joyce. But he didn't like the lipstick she left on his cheek.

Michael and Gwyn slept in the same bed. He dreamed a lot but didn't wake up in the night and they both slept late. When the grown-ups came to bed, Margaret and her mother looked in on them, lying side-by-side, heads nearly touching.

Beatrice said, "They're beautiful kiddies my dear. You're a lucky girl. You've a lot to be proud of."

James gave her a hug just like he used to do when she was his favourite little girl. It nearly made her cry, she was so happy. She was so pleased to have everything in her life, just as she'd always wanted it. Perfect children! Perfect house! Perfect marriage! Everything was quite wonderful!

She was to sleep in the same bed as her youngest sister. It was very late when Julia came into the bedroom. She woke Margaret up, stumbling around the room. Julia didn't smoke but there was the stale aroma of cigarettes from her when she laid herself down beside Margaret. Her breath smelled of gin. Margaret pretended to be asleep. She didn't want to talk to her boozy sister. She dozed off quickly. Julia's snoring in her ear didn't wake her. It had been a long day and she was very tired. She slept the deep sleep of the just.

In the morning, Grandpop, Tom and Julia went to work. Margaret and Gwyn went to have a look round Barrow. Michael said, "I want to stay with Grandma."

Beatrice was pleased and said so. Margaret left him behind. The real reason Michael wanted to stay in the house was not to be with Beatrice. He'd noticed the piano, the one James had bought for Julia. As soon as his mother had gone, he asked Beatrice if he could play the instrument. She smiled benignly on him.

"Of course you can my dear. I'll lift the lid for you. It's a bit heavy. Now mind you don't slam it down on your fingers!"

She went into the kitchen to do some baking. Michael had the time of his life. He banged the keys and sang and shouted along with his discords. It was just like the old days before Margaret got rid of the harmonium.

After half an hour, of listening to his row, Beatrice wished that he'd gone out with his mother!

"Would you like to help me bake Michael?"

"No, I'm all right, thanks Grandma."

Bang! Crash! Wallop!

After the three had come home from work, Margaret and Gwyn returned by bus from the town-centre. They all sat down to lunch together. Afterwards, Tom took them for a car ride. Beatrice stayed at home because she had a bit of a headache. Tom showed them the submarines that were being built at Vickers shipyard. they went over to Walney Island to look at Morecambe on the other side of the Bay.

"I wonder what Dad's doing?" Michael said.

"Getting stuck into the garden I suppose," said Mam.

"If he's stuck, he'll need me to pull him out," said Gwyn.

"Whatever he's doing, it's too far to see from here," laughed Tom. "Come on you kids, I'll race you to the ice-cream man."

They ate their ice-creams sitting on the beach. But it started to rain. So they went back home to Grandma's and Grandpop's. Grandpop was upstairs in bed. "Having forty winks," said Beatrice.

James went out in the early evening. The rest stayed in and played a card game, 'Happy Families'.

"Dad still likes his pint," remarked Margaret.

"Don't we know it!" sighed Beatrice. "He always will. He'll never change."

Michael and Gwyn stayed up very late. It was nine o'clock before Margaret said, "Time for bed for you two!" After the card game they'd played on the carpet. There were toys which Beatrice kept for when any grandchildren stayed with her. Some of them were really old. Michael liked the little wooden train which Grandpop had made many years ago. He would have liked to have kept it for himself but he knew he had lots of cousins who would want to play with it when they visited.

Gwyn's favourite was a china doll. Beatrice had made all the clothes for it, after she'd bought it in a second-hand shop, in Cardiff, in 1913. Michael enjoyed hearing about where all of the different toys had come from.

"Did you play with them when you were a little girl Mam?" asked Gwyn.

Beatrice answered for her, "Oh yes she did! Your Mam was ever such a good little girl. Just like you! There was nothing she liked better than playing quietly with her things. And she was always a good help for me with the little 'uns."

"Who were the little 'uns Grandma?" asked Gwyn.

"I was one," said Tom.

"And I was another," smiled Julia.

Gwyn found it hard to imagine her aunt and uncle as children like her brother and herself.

"Was that in the Olden Days?" she asked, thinking about some of her stories which began, "Once upon a time, long ago, in the Olden Days.."

Everybody laughed when she asked that. Tom said, "You trying to make me into an ancient monument my girl?"

Gwyn was puzzled by their reaction. She frowned at Tom and said, "I'm not your girl. I'm my Dad's girl."

"Not the Olden Days Gwyn! No, my lovely," said Grandma, "it seems more like only yesterday to me. Just like yesterday!" When she said it, she was thinking back to when all of the children were at home. She remembered the infants who had died. It made her feel and look quite sad.

"I'm a bit tired Mam," said Gwyn. "Can I sit on your knee?"

"Here," said Beatrice, "Come and sit on mine!"

Gwyn cuddled up to her and soon fell asleep.

Margaret repeated herself. It was time for bed! This time there was no way round it. They were both very tired. Their protests were not really meaningful. It had been a lovely day.

Playing the piano was what Michael had enjoyed most of all.

"I hope we'll see you again, soon, my lovelies," said Grandma when they left on the Sunday straight after lunch. Grandpop was back in the pub. but he'd left them a shilling each for pocket-money.

Mother and daughter hugged each other.

"Perhaps our Tom will drive you to Lancaster. You still haven't seen our new house," Margaret suggested.

Tom said, "It's a promise. I will when I have the time."

"Some promises are never kept!" thought Margaret, knowing what a full social life Tom had in Barrow.

Gordon was waiting for them when they arrived back in Lancaster.The two children ran along the platform and flung themselves at him, telling him all about what they'd done and what they'd seen. "It was a really good adventure Dad!" said Michael.

"Grandpop gave me a shilling!" said Gwyn.

"I'm pleased. You seem to have enjoyed yourselves," replied Gordon.

"It's nice to be back," Margaret said. "Anything interesting happen while we've been away? Managed to pass the time all right love?"

"It was a bit boring," lied Gordon. "But apart from that everything was fine. Come on, we'll walk! I bet we'll do it quicker than the bus."