Since 1934, Gordon and Margaret had lived for several years in the end

house in Edward Street. The dwellings had been condemned years earlier

as being too damp and dilapidated for human habitation but moving there

had been the first step of what is now called 'upward mobility'. Their

first hovel, where Michael had been born, was in St. Thomas's Place.

It had been much worse, with water running down the walls, and there

was only one bedroom. Michael liked Edward Street, especially now he had his friend, Rob.

They saw each other twice a week at Michael's.

Sometimes, Margaret went up to Williamson's Park, if the weather was good. The

two boys played great adventure games there, exploring its fifty-four

acres more and more widely, finding some of the secret places.

They had an ice-cream or a drink of fizzy pop after they'd finished

their adventures. The mothers sat chatting on their usual seat. The

two boys stayed apart on the grass. Rob said, "I think my Dad might

be going to be a soldier."

"How do you know?"

"I heard him telling my Mam somebody had to stop the bugger. He said

that he needed shooting and he was the man to do it."

Michael took another lick at his ice-cream then asked, "What's a bugger?"

"I think it's another name for a Franco."

Michael wondered why they never went into Rob's house. One day, when

he was playing under the table, he heard his Mam say to his Dad, "It

was pouring down today. We got caught in a really heavy shower but she

couldn't let us in the house. Her husband won't have anybody indoors.

I expect he has his reasons. It takes all kinds I suppose."

"Perhaps they haven't got a lot," said Gordon, "and they don't want

you to see."

"I don't know about that," replied Margaret. "it's a great big posh

house."

Margaret came from a very large gregarious family. Her mother

had always welcomed people indoors.

Michael wondered what Rob's dad was like. Rob never said much about

him or any of his family. He didn't speak about grandparents or aunts

and uncles.

Michael had lots of relatives. Three of his father's aunts lived in

Edward Street. They let him go in all of their houses. He liked going

to Aunt Elsie's best.

All three were Nan's sisters-in-law. Like Nan, they were all war widows.

Their husbands had died with Granddad Eli in France, in 1915 -- and they weren't

the only war widows in Lancaster, by a long shot. Lots of that generation

of women wore black, mourning their lost men for the rest of their lives.

There were long columns of names on Lancaster War Memorial, in a little

garden at the side of the Ashton Hall. One day, on their way to go and

see Nan, Michael's Mam took him and pointed out the name of his Granddad

Eli.

Despite their common tragedy, the three sisters had not bonded with

little, fiery, red-headed Nan. They thought her bossy and a bit snooty.

Elsie said, "I don't know who she thinks she is. She's no better than

us."

Margaret agreed, "I've tried but she's not easy to get on with."

Michael used to hear all sorts of things that grown-ups said, while

he was playing on the floor with his soldiers or looking at his picture

books. He liked it on the floor, on the cool lino. He was fascinated

by the patterns which his Dad had helped to make at work. There were

brown and beige variegated rectangles, all exactly the same size, fitting

together like a perfect jig-saw puzzle.

The aunts were close allies with each other in adversity, including

being against Nan, but they were not always in-and-out of each other's

houses like some. It was only Aunt Elsie of the three who kept open-house

and Margaret and Michael liked her the best.

"Hello love, Hello Michael. Sit yourselves down! I'm glad you've called

in. I'll just put the kettle on. And we'll have a nice little chat.

You have got a few minutes to spare love?"

Margaret always had time to spare. She'd have been disappointed if she

hadn't been asked to stay.

Aunt Elsie was different from the other two aunts in lots of ways. For

a start she'd married again, after the war. She had two children by

her dead, soldier husband and two by Jim, her second. Jim drove one

of the chocolate-and-cream coloured Lancaster buses.

Elsie's youngest child, Joan, was like a big sister to Michael. She

was five years older than he was. When he was a baby, she liked to rock

his pram, play with him on the rug in front of the fire, helped teach

him to crawl, then to walk. Her patience was inexhaustible. She was

a tall child with the red hair and greenish eyes which several of her

family had. In her view, Michael could do no wrong. After Gwyn was born,

she stayed faithful to Michael. She made a fuss of the new baby but

Michael always came first.

Michael loved Joan's pretty, friendly gaze on him. He liked to watch

her when she did things he could not do, like skipping, doing forward-rolls,

keeping a spinning top going with a whip, turning the mangle handle

without help, fetching the bucket filled with coal from the cellar.

She was always calling at Margaret's, when she was not at school, and

Margaret loved to see her.

Joan's mother, Aunt Elsie, had longish, lank, black hair, streaked with

grey. She had grey eyes and pale cheeks. She dressed in black, wore

a slack, formless frock , low-heeled shoes, woollen shawl, thick stockings.

She was lame and carried a walking stick with her, or leaned on it when

she was seated. She was friendly but rarely went out. Her world normally

came to her. The older children, who still lived at home, did the shopping

and most of the housework for her. She had a rocking-chair and spent

most of her time sitting in it, warming herself by the fire and listening

to her wireless.

She asked Margaret what she thought about the King abdicating. Margaret

came from Wales where Edward had curried favour with the miners.

"I think it's a shame. They should have let him marry that woman he

loves. He'd have made a good king."

"Blooming Fascist, that's what I think he is. Him and her! That woman

of his, scrawny bitch, more like a fellah! She's worse than him. Both

of them, always sucking round that Hitler. Wouldn't trust that pair

as far as I can see them!"

"Oh!" replied Margaret. It was all beyond her.

Aunt Elsie was modern in her outlook. She was one of the first in the

street to have a wireless and she read a lot, including the Daily

Herald, a Labour Party newspaper, every day.

There had been a hefty insurance when her first husband was killed.

She bought the house she lived in and was always trying to fight a losing

battle against the jerry-built damp abode. That was how she'd damaged

her leg, doing a bit of plastering all by herself.

She'd slipped off the step-ladder and badly-twisted her knee.

Although her buying of the property had been somewhat ill-advised she

still kept on at Margaret to buy a house.

"Move heaven and earth and move out of that place you're in or you'll

lose your little'un! She'll get pneumonia. Save every penny you can

love, and buy a place of your own! Move to one of the nice new estates!"

Michael wished people would not be for ever talking about moving. He

loved it where he was.

Joan had told him that soon, the Corporation were going to turn the

empty site, straight across from his house, into a children's playground.

There would be a high slide and a roundabout to play on. Joan said boys

and girls would come from all of the other streets nearby to play there

and he'd meet lots of new friends.

"I'll take you over there," she promised. "It'll be really good. You

and Rob will have it all to yourselves when the other children are at

school."

"Will you let me go there, Mam?" asked Michael. You never could tell

with his mother, what she might decide.

"I expect so love, but only if Joan takes you. It'll be alright if Joan

is there to look after you."

"Told you so, didn't I? " laughed Joan. She was really good was Joan. She was always making things happen for him.

Web Links

• Lancaster War Memorial is located in a small Garden of

Remembrance on the east side of the Town Hall. It was designed by

Thomas Mawson and Sons and now commemorates the

dead of both two world wars and other conflicts. 10 bronze panels

at the rear record the names of 1,010 Lancastrians who fell in the First

World War and were dedicated on 3rd December 1924. The

plinth in front of the statue carries the names of a further 300 who fell in

1939-45.

• Westfield War Memorial Village, which was buily in Lancaster in 1924, was initially created for ex-service men, women and families after World War I. The village is owned by registered

charity War Memorial Village Lancaster and is home to 189 ex-service

men, women and families. The homes are leased to Guinness Northern Counties.

Discover a marvellous trip back to Lancaster of the past by author Bill Jervis, which we plan to release in weekly segments. Although the story is set in Lancaster the family and most of the characters within are entirely fictitious -- but this story does chart a way of life largely lost and which many Lancastrians may recall with equal horror and affection...

Wednesday, 28 December 2011

Monday, 5 December 2011

Chapter Ten: Pranks

|

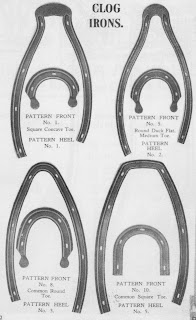

| Clog Irons |

Michael's and Rob's mothers became friends. Mrs Matthews would leave Rob at Michael's while she went shopping. Sometimes, Rob's mother would stay at Michael's and look after the four children, while Michael's mother went up-town.

Michael knew all about Robin Hood and King Arthur and the boys played pretend games and acted the stories. Michael had some lead soldiers which his Dad's mate at work had made for him. Only one soldier was in a coloured uniform. The others were just plain lead.

"Don't suck them! They're poisonous!" warned Michael, repeating what his Dad had told him.

When it was Michael's turn to have the painted one, he imagined it was his heroic Grandad Eli, the one he had never known, the one who had been killed in the war, in 1915. One day, Rob said, "There's going to be another war."

Michael responded with, "Who says so?"

"My dad. He says if we don't listen to Churchill, we'll be in big trouble."

"Who's Churchill?

"I don't know. I haven't asked him."

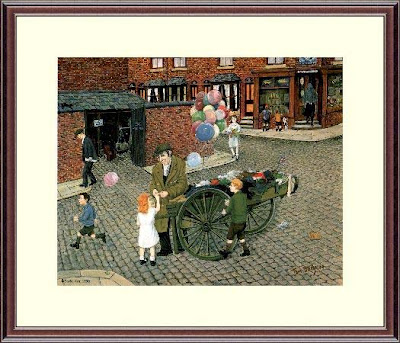

Another time, the two boys were playing out the front and a passing neighbour, Celia Wilkinson, gave them a bobbin with thread on it. Michael knew her friendly face well. She was one of the workers who waved to him when he was watching them all go to the mill on Moor Lane.

She'd nicked it from work, and Michael said, "Coo, it's got miles on it. Let's tie up the houses." So they did.

It was quiet in the street, a mild, spring afternoon, and nobody about. They tied the end of the thread to Michael's front-door knocker and unravelled it carefully down the side alley. They turned left down the back alley, under the shadow of the throbbing mill, and went back into Edward Street from the far-side, near the little shop, which was closed for the afternoon.

Finally, they made their way back up the street, keeping the thread taut across windowsills and across doorways as they went.

They did not snap the thread once. Their mission was completed back at Michael's again. Then they both laughed. They were always laughing. They just saw the funny side of things in the same sort of way.

Another time, Michael said, "Let's go and see my Nan."

"Where does she live?"

"Not far, I know the way," said Michael. "We'll go on our scooters."

"What will our Mams say?"

"Don't worry! It'll be worth it. My Nan always gives me some sweets."

"All right then."

It was a bit steep up Friar Street so they had to stop scooting and pushed their scooters up the slope. They stopped to peep in at the shire horses, which were kept on the left hand side, just across Moor Lane from Mitchell's, in Brewery Lane. The strong horses were used to pull heavy loads all round the town.

Some of the horses were in the shed which acted as their stable. One huge horse was tethered to a post in the middle of the yard. The boys peered at the animals through the spaces between the bars of the wide, high, iron gates.

"See that white one," said Michael, "My Nan's neighbour, Mrs. Wilson, used to own her, when she lived on a canal boat. It's called Florrie and she used to pull a barge."

"Big, aren't they?" said Rob.

"Yes, and they can hurt you," replied Michael. "Mam says I should never try to touch them or stroke them."

"That's all right," said Rob, "I don't want to really anyway do you?"

"No," said Michael, as one of the huge beasts stamped a heavy hoof. The ground shook beneath their feet and the gate they were leaning on rattled. That horse was a real giant.

On an impulse, Michael bent down and picked up a small stone. He threw it at the big horse but missed. It turned its head slowly towards them, more in curiosity than alarm Just then, by coincidence, a man emerged from the shed.

Michael thought he might have seen him throw the pebble. His heart stood still. His stomach turned over.

"Run!" he shouted at Rob. "He's after us!"

The man was only fiddling with the horse's tether but Rob needed no urging. The pair of them hurtled up the hill, dragging their scooters behind them.

There was a perverse pleasure in feeling they were being chased and escaping their pursuer. They liked having adventures together.

They crossed Dalton Square. In the middle of the square they took turns to climb up onto the few-inches-wide edge of the plinth, which supported Queen Victoria's statue. They both managed to go all the way round, rubbing noses on the way with the carvings of eminent Victorians, before they climbed down again to safety. Michael didn't tell Rob that was the first time he'd done it, without his mother helping and waiting to catch him, if he slipped.

They managed to cross the main road without any problems because there was hardly any traffic, even though it was one of the main roads, north and south, through Lancaster.

They passed the end of George Street. They paused and watched a clogger in a leather apron working near the window of the clog repairers in Thurnham Street. The man smiled at them and went on fitting strips of iron to the wooden sole of a clog. The boys turned into Marton Street. Nan's was at the near end and she was really pleased to see them.

She gave them some sweets from the tin which she kept in a cupboard. They sat quietly next to each other on her settee while Nan went on with what she'd been doing.

They watched her take some bread out of the oven at the side of the fire. She turned her bread tins upside down on the well-scrubbed, wooden table and lifted them. Under each one was a fresh loaf.

"Done to a turn. Risen nicely they have!" Nan declared, wiping her hands on her apron, after inspecting her baking for flaws. The aroma from the bread made the boys' nostrils twitch. It smelt lovely. They had an unexpected bonus, when she laid some butter on thickly and gave each of them a bit of the crust off one of her still-hot loaves.

"Just a taster each," said Nan. "Tha mustn't spoil tha teas or I'll have your mothers after me."

They still sat close together on her settee contentedly, eating the bread, sucking the sweets, swinging their legs, talking to Nan.

Then Michael's and Rob's mothers arrived, both frantic, after searching all over the place for the two boys. There was a terrible row. Margaret blamed Nan for the boys' going missing.

"I didn't know they were coming. It's nothing to do with me," Nan protested. "I thought you'd let them come."

"Course I didn't! Would I do that, with that main road to cross?"

"Well it did cross my mind that it was a bit funny but you young ‘uns are always doing funny things."

That did it: they had a real set to.

Michael was smugly pleased. Any anger at what they'd done was turned away from him and he felt satisfied that he was the cause of the commotion. Nan was secretly happy because her grandson had had the urge to come and see her. And she really enjoyed having a go at the silly young thing who had married her Gordon. It was about time that she was put in her place, brought down a peg or two.

Only Margaret lost out, especially as she'd had to beg Next-door to keep an eye on the babies' prams in the yard, while she and Sheila Matthews went looking for the missing boys. Only that morning she had vowed to herself that she wouldn't talk to her unfriendly neighbour again, after further complaints, this time about Margaret overfilling her dustbin and letting rubbish blow about the shared yard.

When Gordon arrived home that evening, Margaret's eyes were still red-rimmed because of all her crying. She poured out her troubles to her husband.

He felt aggrieved. He didn't want to be greeted with all that nonsense. It wasn't the first time and it wouldn't be the last when he felt like piggy-in-the-middle between his wife and mother. He said as little as possible in response to his wife's moaning. "Least said, soonest mended!" he thought.

Web Links of interest

• The English Clog Maker or Clogger

• There are only a very small number of clog makers left from the many hundreds who traded in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Cloggers still trading include Jerry Atkinson, Mike Cahill, Walter Hurst, Trefor Owen, the Turtons, and the Walkleys

• Opened by Samuel Greg & Company in 1826, the steam-powered

cotton-spinning Moor Lane Mill, where Celia worked, was taken over (and fireproofed) by Storey Bros.,

one of Lancaster's leading firms, in 1861. Storeys ceased trading in 1982, and after a period of dereliction then

Council-funded restoration the Grade II Listed mill became the UK

headquarters of Reebok, the sports and footwear company, in 1990. More

recently, it has become NHS offices.

Monday, 28 November 2011

Chapter Nine: Friendship

Friendship

Gordon had three aunts living in Edward Street and half a dozen second-cousins. Margaret had a sister, with her three youngsters, in Lodge Street, not far away. But none of their immediate neighbours were young. This was more of a problem for Margaret than Gordon who had his mates at work.

Margaret came from a very large family and had been used to a noisy house filled with her brothers and sisters. Now, she felt isolated from them and quite lonely. She had plenty to do, looking after the house and the two children, but missed compatible adult company during the day. There were plenty of kids at the far end of the street but most of them looked a bit rough to her. Anyway, Michael was still too young to be allowed to play outside.

One June afternoon, Baby Gwyn was very fractious. Michael's noisy, pretend games were getting on Margaret's nerves. If she put the pram outside in the yard, Next-door would complain about the baby's wailing and Margaret's neglect. She could not put the pram out the front because the pavement was narrow and people would not be able to get past easily.

She was fed up -- stuck inside, with nothing much to do and no one to talk with.

She'd finished her work for the day. She went upstairs and changed into a light, print frock and took her stockings off. Her legs were mottled with scorch marks because she spent so much time sitting close to the fire.

The night before, Gordon had said to her, "For heaven's sake Margaret, do you have to sit in front of the fire, like that? It's summer isn't it? You can't be feeling cold."

But she always did feel cold in the damp house. It was chilly away from the fire. She was only really warm when she was working.

"Well," she thought, "perhaps fresh air will do them good. A bit of sunburn and the brown scorch marks might start to blend with the rest of my skin."

She dressed Michael in a pair of shorts and put his jersey in the pram, in case it turned cold. Under his jersey, she placed her purse. Gwyn was still crying as she laid her in the pram.

Margaret hoped that she would go off to sleep as they walked.

"It'll be nice in the park. I've some stale bread. We'll feed the ducks on the pond." Michael hoped the taking of her purse with them meant she was going to buy some ice-cream or pop when they got there.

They'd only gone as far as the corner of the street when they met one of the great-aunts, who had been up-town shopping. Michael was fed-up because they stopped while she made a fuss of Gwyn. Ignored, he stood there like a prune, all fidgetty, but he daren't protest or misbehave or draw attention to himself, in case his mother decided to take him back home, to sort him out. So he decided to endure Eva's and Margaret's chat without making a commotion.

"Eee! Margaret, isn't she coming on well. Ooo! She looks s right little picture!"

Gwyn stopped crying, and gurgled, when the great-aunt bent over the pram and tickled her. The fussing went on-and-on but at last, Eva went on her way home and they were released to continue their walk.

"Blooming baby!" thought Michael, "Always spoiling things!"

It was really hard going, pushing the pram up Moor Lane, underneath the mill's gantry, over the canal bridge, along St. Peter's Road. It was even steeper and harder going up East Road, past the Grammar School and on, ever higher, past the old Workhouse and school playing-fields, until they finally arrived at an entrance to Williamson's Park.

"I was a good help, wasn't I Mam?" asked Michael, referring to his pushing on the handle of the pram part of the way there.

"Yes, love, you were," his mother responded, wiping the sweat from her forehead. They sat and rested for a few minutes on a seat next to the gatehouse. Gwyn was fast asleep.

"Can I go exploring?" asked Michael, still bursting with energy, although his legs had ached a bit during the climb.

"Yes, but don't go far, I don't want you to be lost."

It was a marvellous park, one of the lino kings' , the Williamsons', many gifts to their home town which, the cynical said, had helped buy the younger one a peerage from his friend, Prime Minister Lloyd George.

The Park was laid out on the instructions of James Williamson (senior), on the site of an old quarry. Local legend had it, that it was done with the cheap labour of his own employees. They'd toiled for a few pence an hour, men laid off from his linoleum works, when trade was slack. It was his son who had carried out major improvements and made it a fine attraction.

James Williamson (junior) was said, at one time, to be the richest man in the world. No-one, well hardly anyone, could argue that at least part of his fortune, earned off the backs of his neighbours, had been spent wisely and for the benefit of Lancaster.

There were varieties of evergreen and deciduous shrubs and trees spread over many acres, on many levels. There was also an incredible monument, to the memory of one of his wives, on high ground reaching up to the sky. Its proportions were monstrous, its architecture bizarre, a sort of St. Paul's Cathedral dome with a Taj Mahal influence. The locals called it disparagingly, 'T'structure'.

There was a long, shallow pool with a fountain and a lovely foot- bridge. There was a huge palm house, an observatory, an interesting temple-folly, a bandstand for Sunday afternoon concerts and paths which wound up and down and round all of the Park.

There were lovely views over Lancaster and far beyond, to the new ever-extending suburban estates You could see all of the way to Morecambe, across the Bay to the hazy Pennines. From the top of the structure, you could, on a clear day, discern the Isle of Man and Blackpool Tower.

Disgruntled by his unpopularity in his home town, James Williamson left Lancaster in 1911 and moved to a new home at Lytham St Anne's. If he ever visited the Park, and climbed to the top of his wife's memorial, he must have felt that much of it was his kingdom that he saw below him and stretched away to the horizon.

There were benches to sit on, lawns, grass to lie on, semi-wild places and hidden groves favoured by courting couples.

There was also a place, beneath the monument and near the bandstand, where they sold refreshments.

After Margaret had had her rest, Michael returned from his exploring. They pushed the pram together round a pathway and came to rest again on a seat near the ice-cream stall. The bench-seat was in the blazing sun but Margaret could stand the heat. She put a white sun-hat on Michael's head.

"We don't want you having sunstroke, do we?" she said to him as she reached for her purse, without waking Gwyn.

"What are you having, an ice-cream or some sweets?"

"Can I have a bottle of pop Mam?"

"Yes, love, and I'll have one too." She found a sixpence from her purse and gave it to him, to go and buy their drinks. He liked the responsibility.

"Don't forget the change and don't drop anything!" she urged as he went. The baby was awake now and whimpering. She lifted Gwyn from the pram to nurse her for a while.

When Michael returned from the queue, Margaret was talking to a woman sitting next to her. There was another pram. The stranger had her baby on her lap and there was a boy, of Michael's age alongside her.

The boy was taller and thinner than Michael. He had auburn hair and a few freckles. He had a coloured, beach-ball under one arm.

"I blew it up myself," said the boy, standing-up, as Michael approached.

"Well most of it," he added, looking at his mother for verification. His mother did not look back at him. She was too busy talking with Margaret, swapping baby stories.

The boy looked at Michael and Michael looked at the boy. Kids are like dogs. A quick mutual appraisal and then the two boys smiled at each other..

The tall boy ran onto the grass and threw the ball into the air. He tried to kick it but he wasn't any good at that. Michael was watching him. Then the boy asked him, "Want to play?"

Michael hesitated but his mother broke off from her conversation, briefly, to urge him, "Go on Michael. Go on!"

Michael put his bottle of pop down and went to join the boy. They played for ages, following the bouncy ball all over the flat grass. Then they left the ball with their mothers and went up the slope and climbed some of the steps of the monument and played hide-and-seek round it.

Before they went back to their mothers, the tall boy showed Michael how to lie down and then roll sideways all the way down the slope to the level grass. It was fun. Michael wanted to keep on doing it but it was time to go The babies needed changing and feeding.

"Blooming baby!" said Michael.

"Blooming baby!" said the tall boy.

Then they both laughed.

"Michael, say thank-you to Rob, for letting you play with his ball!"

"Thank-you, Rob!"

The boys waved to each other when they parted. Michael hoped that he'd meet Rob again.

Little did he know, but it was the beginning of a lifelong friendship.

Gordon had three aunts living in Edward Street and half a dozen second-cousins. Margaret had a sister, with her three youngsters, in Lodge Street, not far away. But none of their immediate neighbours were young. This was more of a problem for Margaret than Gordon who had his mates at work.

Margaret came from a very large family and had been used to a noisy house filled with her brothers and sisters. Now, she felt isolated from them and quite lonely. She had plenty to do, looking after the house and the two children, but missed compatible adult company during the day. There were plenty of kids at the far end of the street but most of them looked a bit rough to her. Anyway, Michael was still too young to be allowed to play outside.

One June afternoon, Baby Gwyn was very fractious. Michael's noisy, pretend games were getting on Margaret's nerves. If she put the pram outside in the yard, Next-door would complain about the baby's wailing and Margaret's neglect. She could not put the pram out the front because the pavement was narrow and people would not be able to get past easily.

She was fed up -- stuck inside, with nothing much to do and no one to talk with.

She'd finished her work for the day. She went upstairs and changed into a light, print frock and took her stockings off. Her legs were mottled with scorch marks because she spent so much time sitting close to the fire.

The night before, Gordon had said to her, "For heaven's sake Margaret, do you have to sit in front of the fire, like that? It's summer isn't it? You can't be feeling cold."

But she always did feel cold in the damp house. It was chilly away from the fire. She was only really warm when she was working.

"Well," she thought, "perhaps fresh air will do them good. A bit of sunburn and the brown scorch marks might start to blend with the rest of my skin."

She dressed Michael in a pair of shorts and put his jersey in the pram, in case it turned cold. Under his jersey, she placed her purse. Gwyn was still crying as she laid her in the pram.

Margaret hoped that she would go off to sleep as they walked.

"It'll be nice in the park. I've some stale bread. We'll feed the ducks on the pond." Michael hoped the taking of her purse with them meant she was going to buy some ice-cream or pop when they got there.

They'd only gone as far as the corner of the street when they met one of the great-aunts, who had been up-town shopping. Michael was fed-up because they stopped while she made a fuss of Gwyn. Ignored, he stood there like a prune, all fidgetty, but he daren't protest or misbehave or draw attention to himself, in case his mother decided to take him back home, to sort him out. So he decided to endure Eva's and Margaret's chat without making a commotion.

"Eee! Margaret, isn't she coming on well. Ooo! She looks s right little picture!"

Gwyn stopped crying, and gurgled, when the great-aunt bent over the pram and tickled her. The fussing went on-and-on but at last, Eva went on her way home and they were released to continue their walk.

"Blooming baby!" thought Michael, "Always spoiling things!"

It was really hard going, pushing the pram up Moor Lane, underneath the mill's gantry, over the canal bridge, along St. Peter's Road. It was even steeper and harder going up East Road, past the Grammar School and on, ever higher, past the old Workhouse and school playing-fields, until they finally arrived at an entrance to Williamson's Park.

"I was a good help, wasn't I Mam?" asked Michael, referring to his pushing on the handle of the pram part of the way there.

"Yes, love, you were," his mother responded, wiping the sweat from her forehead. They sat and rested for a few minutes on a seat next to the gatehouse. Gwyn was fast asleep.

"Can I go exploring?" asked Michael, still bursting with energy, although his legs had ached a bit during the climb.

"Yes, but don't go far, I don't want you to be lost."

It was a marvellous park, one of the lino kings' , the Williamsons', many gifts to their home town which, the cynical said, had helped buy the younger one a peerage from his friend, Prime Minister Lloyd George.

The Park was laid out on the instructions of James Williamson (senior), on the site of an old quarry. Local legend had it, that it was done with the cheap labour of his own employees. They'd toiled for a few pence an hour, men laid off from his linoleum works, when trade was slack. It was his son who had carried out major improvements and made it a fine attraction.

James Williamson (junior) was said, at one time, to be the richest man in the world. No-one, well hardly anyone, could argue that at least part of his fortune, earned off the backs of his neighbours, had been spent wisely and for the benefit of Lancaster.

There were varieties of evergreen and deciduous shrubs and trees spread over many acres, on many levels. There was also an incredible monument, to the memory of one of his wives, on high ground reaching up to the sky. Its proportions were monstrous, its architecture bizarre, a sort of St. Paul's Cathedral dome with a Taj Mahal influence. The locals called it disparagingly, 'T'structure'.

There was a long, shallow pool with a fountain and a lovely foot- bridge. There was a huge palm house, an observatory, an interesting temple-folly, a bandstand for Sunday afternoon concerts and paths which wound up and down and round all of the Park.

There were lovely views over Lancaster and far beyond, to the new ever-extending suburban estates You could see all of the way to Morecambe, across the Bay to the hazy Pennines. From the top of the structure, you could, on a clear day, discern the Isle of Man and Blackpool Tower.

Disgruntled by his unpopularity in his home town, James Williamson left Lancaster in 1911 and moved to a new home at Lytham St Anne's. If he ever visited the Park, and climbed to the top of his wife's memorial, he must have felt that much of it was his kingdom that he saw below him and stretched away to the horizon.

There were benches to sit on, lawns, grass to lie on, semi-wild places and hidden groves favoured by courting couples.

There was also a place, beneath the monument and near the bandstand, where they sold refreshments.

After Margaret had had her rest, Michael returned from his exploring. They pushed the pram together round a pathway and came to rest again on a seat near the ice-cream stall. The bench-seat was in the blazing sun but Margaret could stand the heat. She put a white sun-hat on Michael's head.

"We don't want you having sunstroke, do we?" she said to him as she reached for her purse, without waking Gwyn.

"What are you having, an ice-cream or some sweets?"

"Can I have a bottle of pop Mam?"

"Yes, love, and I'll have one too." She found a sixpence from her purse and gave it to him, to go and buy their drinks. He liked the responsibility.

"Don't forget the change and don't drop anything!" she urged as he went. The baby was awake now and whimpering. She lifted Gwyn from the pram to nurse her for a while.

When Michael returned from the queue, Margaret was talking to a woman sitting next to her. There was another pram. The stranger had her baby on her lap and there was a boy, of Michael's age alongside her.

The boy was taller and thinner than Michael. He had auburn hair and a few freckles. He had a coloured, beach-ball under one arm.

"I blew it up myself," said the boy, standing-up, as Michael approached.

"Well most of it," he added, looking at his mother for verification. His mother did not look back at him. She was too busy talking with Margaret, swapping baby stories.

The boy looked at Michael and Michael looked at the boy. Kids are like dogs. A quick mutual appraisal and then the two boys smiled at each other..

The tall boy ran onto the grass and threw the ball into the air. He tried to kick it but he wasn't any good at that. Michael was watching him. Then the boy asked him, "Want to play?"

Michael hesitated but his mother broke off from her conversation, briefly, to urge him, "Go on Michael. Go on!"

Michael put his bottle of pop down and went to join the boy. They played for ages, following the bouncy ball all over the flat grass. Then they left the ball with their mothers and went up the slope and climbed some of the steps of the monument and played hide-and-seek round it.

Before they went back to their mothers, the tall boy showed Michael how to lie down and then roll sideways all the way down the slope to the level grass. It was fun. Michael wanted to keep on doing it but it was time to go The babies needed changing and feeding.

"Blooming baby!" said Michael.

"Blooming baby!" said the tall boy.

Then they both laughed.

"Michael, say thank-you to Rob, for letting you play with his ball!"

"Thank-you, Rob!"

The boys waved to each other when they parted. Michael hoped that he'd meet Rob again.

Little did he know, but it was the beginning of a lifelong friendship.

Saturday, 1 October 2011

Chapter Eight: The Trial of Buck Ruxton

The Ruxtons

(A Drama About A Lancaster Othello)

Red stains in the sunset,

Red stains on the knife,

Old Dr. Ruxton you murdered your wife.

The maid came and caught you,

You murdered her too,

Now Dr Ruxton what are we to do?

They'll hang you tomorrow,

They'll not spare you 'tis sure,

And then Dr Ruxton will murder no more.

Red Stains on the carpet,

Why Dr. Ruxton did you murder your wife?

Those were the verses on the broad-sheet which was circulated when Dr. Ruxton was tried, at Manchester, in 1936.

The Trial

For the Defence: Norman Birkett K.C.

For the Prosecution: Mr. Jackson K.C.

The Judge: Mr. Justice Singleton

The Deceased: Isabelle Ruxton, wife of the accused.

Mary Rogerson, the live-in maid.

Other Victims: The Three Orphaned Ruxton Infants.

The Evidence: Circumstantial.

Important Witnesses:

Forensic Professor Glaister

Lancaster's Chief Constable Vann

Dentist, Lovers? Friends, Trades People and Employees of the Ruxtons

Inside and outside the court, in the pubs, on the doorsteps and in the market a cast of thousands of Lancastrians, all with a story to tell, or rumours to spread, about the strange goings-on of Buck and Isabelle Ruxton and the tragedy of the murders.

Buck Ruxton, described in the local press as a Mohammedan, of mixed French and Indian blood, was an exotic figure in a Lancaster unused to seeing people other than whites, all speaking with the distinctive local or regional accent.

Curiously, Gordon's wife, British but Welsh-born, had been seen as a weird foreigner when she first moved to Morecambe. She had been humiliated by her teacher, because of her accent, and ridiculed by some of her class-mates at Balmoral School, when she first arrived. Perhaps they thought that she was Irish, who were all, usually without justification, disliked and distrusted.

Nobody worried about Dr. Ruxton's background. With over two thousand patients on his panel, cheap fees, pleasant bedside manner, many friends amongst the workers he served, Buck Ruxton quickly became something of a local hero. He claimed to be the most progressive doctor in the area and the only people who disliked him were some of his colleagues, rivals for panel patients. Maybe, he exaggerated when boasting of his medical prowess but there was some truth in his extravagant claims. Certainly, he had the trust of his patients.

The Watsons had plenty of reason to be grateful to him. He had delivered their two children safely and skilfully despite two difficult births.

"Best doctor in the world!" was Margaret's verdict.

His care of their little, delicate Gwyn, during the first winter of her life, was meticulous and affordable. The doctor had never given up when Gordon and Margaret had despaired and begun to think that the child had no hope of surviving something very close to the dreaded pneumonia.

Soon, he was to be fighting for his own life. Although both of Watsons thought that he was probably guilty, they did not want him to die. But why had he killed the housemaid? That was not easy to understand or forgive.

Rumours had been rife in Lancaster about "goings-on" amongst some of the local Authority figures. The finger was pointed at Bobby Edmondson, a solicitor in the Town Clerk's Office. Many believed that he and Isabelle had been having an affair.

A bizarre rumour even suggested there had been a lesbian relationship with Bobby's sister, Barbara. "Why did they have rooms next to each other when they went as part of a group to Edinburgh for a weekend?"

There were dark hints about "Isabelle's masculine looks and thick ankles! Farcical fantasies were on many gossips' lips.

Mixed parties, including Isabelle, visiting places like Edinburgh and Blackpool were known about and viewed with intense suspicion. There were many witnesses, like Gordon, who had seen Buck beside himself with rage, after his wife had returned from one of her jaunts. She liked going away without him for a weekend and often stayed out late at night. Twice, she sought police protection after he had threatened her life during one of his jealous rages.

Lancaster Footlights, in China Street, was under suspicion.

"Actors are a funny lot, aren't they? Wasn't Isabelle Ruxton an active member there?"

Someone else said that their brother-in-law's brother's wife's sister was a waitress at the Conservative Club in Church Street. The distant relative of the rumour-monger had allegedly worked in a noisy mill and could lip-read. She said she'd observed two prominent local Freemasons discussing some of the disturbing evidence against a local solicitor. She insisted she'd seen them agree that any nasty publicity, arising from the murder case, could be held back with the help of a few weird handshakes and a nod to the judge.

People reported mixed bathing, cavorting and assignments at Cable Street Baths.

Afterwards, Isabelle was seen going home in another man's car!

There were dozens of reported sightings of the Ruxton or Edmondson car, parked at the end of lonely lanes or on quiet sea shores.

If only a fraction of the stories came to poor Buck's ears, it must have driven him to distraction because he loved Isabelle dearly. Certainly his outbursts from the dock were very convincing. He stated again and again that he was being victimised by the police.

The remains of two bodies had been found in a ravine in Scotland, wrapped in pages of a newspaper which had had a limited edition circulated in the Lancaster and Morecambe area.

Who were the missing persons from that area? Isabelle and Mary!

Forensic evidence, and new methods used to identify victims, proved that the body parts were the two women's.

Blood in the drains at Ruxton's! Bloody clothing burned there! Bloody carpets incinerated! Dustbins filled with bits of burned fabric! Bloodstains here and there in the house! Employees bore witness to a variety of frenzied and prolonged efforts to dispose of what might have been evidence.

The theory was that he had probably strangled one and stabbed the other victim. Using his surgeon's skills, including removal of some finger-tips, to prevent identification by finger-prints, he had cut the bodies up, using ordinary household knives, parcelled them, put them in the boot of his car and driven to Scotland, thrown the parcels down a ravine and driven back to Lancaster at breakneck speed, anxious to establish an alibi.

Dental evidence helped to establish that Isabelle and Mary were definitely the victims.

Chief Constable Vance had sat in the Police Station on one side of Dalton Square. Buck Ruxton had sat in his house directly opposite. The Police Station was fully visible from the Doctor's House. The detective could see the lights on late at night at Ruxton's. Dalton Square was like a stage with characters in a life-or-death drama. The main players strutted across it, playing their roles of hunter and hunted. Both used their considerable brain-power, trying to outwit the other. Both pondered the lack of concrete evidence. The new art of detection using a forensic expert was to be crucial.

Vance ordered sudden action and accompanied unexpected visits to the Doctor's House and searched everywhere thoroughly, even taking the floorboards up.

Anxious and restless, Doctor Ruxton crossed Dalton Square, visited the Police Station and said, "Look here Vann, haven't you found my wife yet? It's outrageous. They're trying to say these two bodies in Scotland are my wife and Mary Rogerson. It's ruining my practice. You must stop the newspapers from publishing such lies."

"What makes you so sure it isn't true, Doctor?" asked Vann.

"Well, here it says the younger of the two dead women, found in Scotland, has a full set of teeth in the lower jaw and I know from my own knowledge that both my wife and Mary Rogerson had teeth missing."

Slowly but surely, convincing circumstantial evidence was building up against the doctor. The police became convinced that he was guilty and that it could be proved.

Vann spoke to his men, "I think it's time we had him over here again."

Detective Inspector Bill Thompson agreed, "I think chummie across the Square is getting a bit desperate. Take care! Remember he has a revolver in that house, sir."

Vann picked up the 'phone, "Doctor Ruxton? Vann here. Those newspaper stories you complained about. I think we can put a stop to that sort of nonsense. Why not come to see me tonight?"

Buck rushed across the Square again, for another of their little chats, each man wary of the other, trying to detect what was in the other's mind.

The Doctor protested that he was the victim of jealous professionals. Lancaster's middle-class was ganging-up against him. Many workers, especially amongst his patients, believed his loud protestations of innocence and agreed with his objections, that he was being persecuted on very little, or no evidence. He had lots of letters of support from local people.

Gordon and Margaret read the notice on his surgery door, in the middle of October.

"To all my patients.

I appeal to you most humbly to remain loyal to me in this hour of trouble. I am an innocent victim of circumstances. Please do not leave my panel list as well as private list. My deputy will conduct business as usual.

Thanking you in anticipation for loyal support.

Signed,

B. RUXTON."

Many did stay loyal to the accused. For a time, Margaret went along with Buck's conspiracy theory. She thought he was the scapegoat, that there was a cover-up. It was Them behind it and they were getting at one of Us.

Gordon wasn't so sure, "You didn't see his face that night when I went for him to help you. He was out of his mind."

"It doesn't follow he really meant to hurt her," she said. "Anyone can lose their temper. You said he soon calmed down."

"Maybe only because he saw me standing there, watching him."

Chief Constable Vann had Buck arrested at five o'clock one morning, convinced that he'd got his man. There was plenty of sympathy for him in the town but all the evidence was against him during his police court appearances in Lancaster.

After his arrest, the kitchen staff of the cafe, where he had often eaten, sent a message with a meal he was allowed in the cells, "Good luck from the kitchen staff."

He wrote back on the serviette, which came with the food, "Thanks for the wishes and luck. It is surely coming my way, B. Ruxton."

During his trial, at Manchester, he took the oath on the New Testament although he was thought to be a Mohammedan or Parsee. He was said to be calm until he went into the witness box at the Assizes.

His relaxed manner was not to last. It was reported, "I most devoutly hope that I shall never again see a man or a woman or a child behave as Doctor Buck Ruxton did during the hours of his examination, cross-examination and re-examination. He cried, was excited, voluble, almost hysterical. Denunciations poured from him like water bursting out of a dam. Then he would beg forgiveness for his bad behaviour in court. His voice varied from beautiful modulation to shrieks."

When Professor Glaister maintained that he should never have worn the dirty suit which he wore during confinements, he shook with rage and beat his hands up and down in anger.

"I can only give one answer. Out of 230 confinements in Lancaster, Doctor Ruxton has never given a death certificate. You can verify that from the L.C.C. Authority. I will give £500 for it. I go by results, not theories. 230 cases and not a death certificate given!"

It was a remarkable demonstration of his professional pride. Sometimes he addressed Professor Glaister as , "Dear fellow" or "valued colleague". Next, he was protesting that everything and everyone was against him.

He pleaded with the judge to forgive his outbursts with, "I am sorry, very sorry sir. It is my fault. But I am fighting for my life. FOR MY LIFE! I must humbly, most humbly, beg your pardon for interrupting."

The report went on, "It was terrible to see an educated man go through such an ordeal and I pitied him."

He stated that he would have had to drive at over 100 m.p.h., on dangerous roads, to dispose of the body-parts in distant Scotland and be back by the hour he was next seen in Lancaster.

Just before and during the judge's summing up, his left arm was doubled on his knees, his face was cupped in the palm of his right hand. At one stage he even yawned, feigning boredom. The judge emphasised that any doubt must go to the prisoner.

The jury returned after an hour. Guilty! Was their verdict. The judge sentenced him with the words, "You have been convicted on evidence which could leave no doubt in the mind of anyone."

Ruxton seemed dazed and beaten. He muttered to himself. He smiled and nodded.

The judge pronounced a sentence of death.

Surrounded by four warders, Ruxton raised his right hand and said, "Don't fuss. I am alright. Don't fuss!"

There was a petition for clemency in Lancaster. More than 16,000 signed it.

One patient expressed the general feelings for the man, "Ruxton was clever, generous and helpful and I cannot but join in the general sympathy for him despite the fact that he has been proved guilty of a very terrible crime."

The fingers were still being pointed at Authority, "He was never allowed access or facilities at Lancaster Royal Infirmary."

His well-known adoration of his and other people's children was mentioned by many. People wondered what would become of his poor little children. After his execution, it was said that they went to the old workhouse, then to Buck's parents or were adopted. No-one knew for sure but their ordeal must have been terrible.

His trial had lasted 11 days in March, 1936. In the May, he was hanged by the neck until he was dead in Strangeways Prison, Manchester. It was stated that before his execution he admitted that he was guilty of the two murders.

The day after Buck was hanged, Gordon met his best friend Brian Howson. Brian had a black eye.

"Who gave you the shiner?" asked Gordon.

"Got into an argument about whether Buck Ruxton should be hanged. Bloke disagreed with me. He came on strong about him being a nasty, filthy wog. I said my bit back. And the bloke hit me. Bloody Fascist!"

The arguments, rights and wrongs of the case, raged for years in Lancaster. Amongst many, there remained an uneasy feeling that there were things going on in their town which only a few were privileged to know about.

Yes, he was guilty all right, but he'd been treated badly at times by some of his own colleagues and others in their circle. He had definitely been very severely provoked by his wayward wife.

Web Links

• A tour of Buck Ruxton's House on virtual-lancaster

• A newspaper article in The Guardian on the Natural History Museum’s forensic entomologists on their role in solving murders revealed that the Museum holds the Ruxton maggots, vital evidence in one of the most celebrated murder cases of the 20th century that convicted Dr Buck Ruxton of the murder of his wife and the family maid.

• Glasgow University Archives holds the Buxton Case File [Ref. GUAFM/2A/25] which contains notebooks, correspondence, anatomical reports, witness reports, extracts from Ruxton’s diary, photographs, and lantern slides relating to the legal case. The material forms part of the important Glasgow University forensic medicine resource whiich contains a wide range of research material relating to a variety of fields including the history of medicine, criminology, sociology, and medical ethics. The records consist of teaching materials, correspondence, press cuttings, personal papers, photographs, and detailed case notes relating to some of Glasgow and Scotland’s most notorious crimes.

Labels:

Buck Ruxton,

Cable Street Baths,

Chief Constable Vann,

Forensic Professor Glaister,

Isabelle Ruxton,

Lancaster Footlights,

Mary Rogerson,

Mr. Jackson K.C.,

Mr. Justice Singleton,

Murder,

Norman Birkett K.C.

Chapter Seven: Dalton Square

Gordon liked to make the most of his weekends. It was a bit of alright

having a lie-in and a late breakfast. After that, weather permitting,

he felt the need for fresh air. When he'd been outside earlier, he'd

noticed it was very warm for the time of year so he suggested, "As it's

a nice day and I'm cooped up all week at work , maybe I'll take Michael

for a walk."

"Hurrah!" said Michael.

"Oh no you don't!" retorted Margaret. "I've the baby to see to most of the time. I think you should have your share at weekends."

It was out of the question that he should be seen pushing a pram, in the town, so he couldn't take Gwyn. Pushing prams was a woman's job. On the other hand, he didn't want a row because he was hoping for a bit of loving that evening.

"Tell you what, we'll let Gwyn have a bit more sleep," he suggested, trying to find a solution to his wife's demands, "then how about us all going to see your mum and dad at Torrisholme? You can take some of our joint of beef with us and Grandma will soon find some extra vegetables for us, won't she Michael?"

Margaret's face brightened at the prospect and Michael shouted out with glee, loud enough to wake the baby up, which meant they could get ready right away.

Their house was on the end of Edward Street. They crossed the road and walked down Moor Lane, past Riley's, the grocer's shop window. It was nearly 11 o'clock and the town's church bells were ringing. On the opposite side of Moor Lane was St. Anne's Church, where Michael was soon to start Sunday School. A few people were just going in.

The bells of the Roman Catholic Cathedral of St. Peter, not far from the top of Moor Lane, could be heard, while the ringers at St. Mary's, near Lancaster Castle, were competing well. Michael thought they all sounded lovely.

Further down Moor Lane there was a variety of shops, including the newsagents. Gordon did not usually take an evening paper but since Dr. Ruxton's arrest for murder, in October, he'd been stopping there every day on his way home, to buy the local edition of the Lancashire Evening News. It was printing all the gory details as they unfolded during the investigation, arrest, police court appearances and trial of the accused man.

This Sunday morning, the newsagents excepted, all of the shops, including Riley's, were closed and the only people about were churchgoers. Everybody, apart from those who couldn't afford any, were wearing their best clothes, which they only wore on Sundays or for other very special occasions. It would be the same when the pubs opened. The men would go there in their Sunday outfits. In the afternoon, people going to take flowers to their dead in the cemeteries, or out for a relaxing walk, would wear their best attire. Indoors, many would put on their glad rags, in case they had visitors.

Usually, Margaret worked all morning making Sunday dinner, but after she had washed up she'd say to Gordon, handing him the baby, "Here love, look after her a minute, I'm just going up to change."

Half an hour later, she'd come back down in a nice, new frock she'd made for herself. She'd brushed her dark hair, rubbed in some face cream, powdered her cheeks and smeared a hint of lipstick onto her mouth.

Gordon kept on glancing at his wife. He could have done worse, he thought.

She wasn't letting herself go. Jet black hair, chameleon eyes, very

slim, lilting Welsh accent, kind face. Nicely turned out. No curlers.

Pity about her legs and teeth. Not her fault, he supposed. They couldn't

afford a dentist. And it being so cold and damp in the house, he could

hardly blame her for huddling over the fire and scorching her legs.

He wished that she wouldn't though because she had nice legs.

"How'd I look?" she'd giggle, pleased with her transformation. Once, Gordon put the baby down on the rug in front of the fire, took his wife in his arms and swung her round off her feet. Then he sat down with her on his lap and tickled her knees. That made her giggle a lot more.

"Stop it, Dad! You're hurting her. She doesn't like it," cried Sir Galahad, in the guise of Michael.

Margaret struggled free, stood up and smoothed herself down.

"I'll deal with you later," laughed Gordon. Michael did not understand what he meant by that. As his mother giggled again, he didn't worry.

Just before they turned left out of Moor Lane and passed the turning to Bulk Street, Gordon paused and took a deep breath. "Lovely!" he exclaimed.

He was referring to the smell of beer coming from Mitchell's, down Brewery Lane.

"Revolting more like it!" responded Margaret. Michael didn't like it either. Depending on which way the wind was blowing, he could sometimes smell it when he was lying in bed. He didn't like it at all. He agreed with his mother, it was revolting.

They went past where the shire horses were kept just round the next turning. They carried on up the slope and onto Dalton Square. The clock, on the far side of the Square, on top of the imposing Ashton Hall, was showing eleven and a bus for Morecambe was just leaving. It would be half an hour before the next one.

Margaret blamed her husband. "If you hadn't stopped to act the fool, sniffing that beer, we'd have been just right."

Gordon put on a brave face.

"Never mind love, it's not cold. We can go and sit in the park and Michael can have a run around in there."

Margaret handed over the baby, "Here, you take her, she's getting heavy."

Then she led the way into the little Park, in the middle of the Square, the one where the huge statue of little Queen Victoria was situated. It dominated everyone and everything she surveyed from the top of her plinth. People were sitting on the seats at the side of the circular path and there were a few weary blossoms still flowering in the flower beds.

It being such a nice morning, for December, most of the bench seats were occupied but a fat woman in a black hat and a thin man in a brown one moved up to let Margaret and Gordon sit down. Michael went to play on the steps around Queen Victoria's statue. Margaret was staring at the tall house, next to the County Cinema, on the side of the Square, facing the Ashton Hall.

"I feel sorry for him," she said, "I really do." She didn't have to explain who she meant. It was Buck Ruxton's house she was looking at.

"I know what you mean love," agreed Gordon, "knowing him like we do. I must say I feel a bit guilty that I didn't take more notice when I saw him having a go at her last year when you were having Gwyn."

"Don't be silly! It's not for us to tell doctors how to behave."

Three other local people, waiting there for the bus, started to join in the conversation and discuss the recent murder of the doctor's wife and his housemaid.

Many folk had a story to tell about the Ruxtons. Gordon told his to the couple sitting next to him.

"I don't think he was going to hurt her with the knife I saw," concluded Gordon. "I think I'd probably disturbed him at his supper."

"Bit late to be having his supper, wasn't it?" said the thin man.

"Lucky he didn't make a real meal of her there and then from what you've just told us," observed the fat woman.

Nobody laughed.

"He was driven to it, she was a wrong 'un."

"Aye, but he shouldn't have hurt the housemaid."

"True!"

"They'll hang him, they've said they will."

"Serve him right!"

"I don't agree with that."

The discussion was becoming animated, so Gordon went over to Michael.

He didn't want an argument but he was against capital punishment. Wherever

you went, people in Lancaster were taking sides for-and-against the

popular doctor, eventually to be hanged at Strangeways, in Manchester.

Many remembered his kindness. Nothing too much trouble for his patients, in a mainly low-paid, working-class area. His fees were modest and he refused any payment from destitute sick people. It was a real tragedy all round.

"But he shouldn't have harmed the girl!" said the fat woman. And for many, that settled the matter: he deserved to hang.

"Hurrah!" said Michael.

"Oh no you don't!" retorted Margaret. "I've the baby to see to most of the time. I think you should have your share at weekends."

It was out of the question that he should be seen pushing a pram, in the town, so he couldn't take Gwyn. Pushing prams was a woman's job. On the other hand, he didn't want a row because he was hoping for a bit of loving that evening.

"Tell you what, we'll let Gwyn have a bit more sleep," he suggested, trying to find a solution to his wife's demands, "then how about us all going to see your mum and dad at Torrisholme? You can take some of our joint of beef with us and Grandma will soon find some extra vegetables for us, won't she Michael?"

Margaret's face brightened at the prospect and Michael shouted out with glee, loud enough to wake the baby up, which meant they could get ready right away.

|

| Where St. Annes Church used to be today |

Their house was on the end of Edward Street. They crossed the road and walked down Moor Lane, past Riley's, the grocer's shop window. It was nearly 11 o'clock and the town's church bells were ringing. On the opposite side of Moor Lane was St. Anne's Church, where Michael was soon to start Sunday School. A few people were just going in.

The bells of the Roman Catholic Cathedral of St. Peter, not far from the top of Moor Lane, could be heard, while the ringers at St. Mary's, near Lancaster Castle, were competing well. Michael thought they all sounded lovely.

Further down Moor Lane there was a variety of shops, including the newsagents. Gordon did not usually take an evening paper but since Dr. Ruxton's arrest for murder, in October, he'd been stopping there every day on his way home, to buy the local edition of the Lancashire Evening News. It was printing all the gory details as they unfolded during the investigation, arrest, police court appearances and trial of the accused man.

This Sunday morning, the newsagents excepted, all of the shops, including Riley's, were closed and the only people about were churchgoers. Everybody, apart from those who couldn't afford any, were wearing their best clothes, which they only wore on Sundays or for other very special occasions. It would be the same when the pubs opened. The men would go there in their Sunday outfits. In the afternoon, people going to take flowers to their dead in the cemeteries, or out for a relaxing walk, would wear their best attire. Indoors, many would put on their glad rags, in case they had visitors.

Usually, Margaret worked all morning making Sunday dinner, but after she had washed up she'd say to Gordon, handing him the baby, "Here love, look after her a minute, I'm just going up to change."

Half an hour later, she'd come back down in a nice, new frock she'd made for herself. She'd brushed her dark hair, rubbed in some face cream, powdered her cheeks and smeared a hint of lipstick onto her mouth.

|

| Queen Victoria statue, Dalton Square, Lancaster |

"How'd I look?" she'd giggle, pleased with her transformation. Once, Gordon put the baby down on the rug in front of the fire, took his wife in his arms and swung her round off her feet. Then he sat down with her on his lap and tickled her knees. That made her giggle a lot more.

"Stop it, Dad! You're hurting her. She doesn't like it," cried Sir Galahad, in the guise of Michael.

Margaret struggled free, stood up and smoothed herself down.

"I'll deal with you later," laughed Gordon. Michael did not understand what he meant by that. As his mother giggled again, he didn't worry.

Just before they turned left out of Moor Lane and passed the turning to Bulk Street, Gordon paused and took a deep breath. "Lovely!" he exclaimed.

He was referring to the smell of beer coming from Mitchell's, down Brewery Lane.

"Revolting more like it!" responded Margaret. Michael didn't like it either. Depending on which way the wind was blowing, he could sometimes smell it when he was lying in bed. He didn't like it at all. He agreed with his mother, it was revolting.

They went past where the shire horses were kept just round the next turning. They carried on up the slope and onto Dalton Square. The clock, on the far side of the Square, on top of the imposing Ashton Hall, was showing eleven and a bus for Morecambe was just leaving. It would be half an hour before the next one.

Margaret blamed her husband. "If you hadn't stopped to act the fool, sniffing that beer, we'd have been just right."

Gordon put on a brave face.

"Never mind love, it's not cold. We can go and sit in the park and Michael can have a run around in there."

Margaret handed over the baby, "Here, you take her, she's getting heavy."

Then she led the way into the little Park, in the middle of the Square, the one where the huge statue of little Queen Victoria was situated. It dominated everyone and everything she surveyed from the top of her plinth. People were sitting on the seats at the side of the circular path and there were a few weary blossoms still flowering in the flower beds.

It being such a nice morning, for December, most of the bench seats were occupied but a fat woman in a black hat and a thin man in a brown one moved up to let Margaret and Gordon sit down. Michael went to play on the steps around Queen Victoria's statue. Margaret was staring at the tall house, next to the County Cinema, on the side of the Square, facing the Ashton Hall.

"I feel sorry for him," she said, "I really do." She didn't have to explain who she meant. It was Buck Ruxton's house she was looking at.

"I know what you mean love," agreed Gordon, "knowing him like we do. I must say I feel a bit guilty that I didn't take more notice when I saw him having a go at her last year when you were having Gwyn."

"Don't be silly! It's not for us to tell doctors how to behave."

Three other local people, waiting there for the bus, started to join in the conversation and discuss the recent murder of the doctor's wife and his housemaid.

Many folk had a story to tell about the Ruxtons. Gordon told his to the couple sitting next to him.

"I don't think he was going to hurt her with the knife I saw," concluded Gordon. "I think I'd probably disturbed him at his supper."

"Bit late to be having his supper, wasn't it?" said the thin man.

"Lucky he didn't make a real meal of her there and then from what you've just told us," observed the fat woman.

Nobody laughed.

"He was driven to it, she was a wrong 'un."

"Aye, but he shouldn't have hurt the housemaid."

"True!"

"They'll hang him, they've said they will."

"Serve him right!"

"I don't agree with that."

|

| The Golden Lion, Moor Lane |

Many remembered his kindness. Nothing too much trouble for his patients, in a mainly low-paid, working-class area. His fees were modest and he refused any payment from destitute sick people. It was a real tragedy all round.

"But he shouldn't have harmed the girl!" said the fat woman. And for many, that settled the matter: he deserved to hang.

Sunday, 4 September 2011

Chapter 6: Sunday Morning

One bright Sunday morning in December, Michael lay awake in his bed thinking. "It's not fair, I'm here all on my own, just because they have a baby."

From the other bedroom, there came his Mam's quiet singing and soothing words as she fed Gwyn. The baby was crying. It seemed to Michael that she spent most of her time crying. He was fed up with having to be quiet when she was asleep and having to be silent when his mother was trying to coax her to sleep. All she did was lie in her pram or cot or be carted about in his mother's arms. She was a dead loss. She was boring. She couldn't play any games. And she'd wet right down him when his Mam once asked him to hold her. Blooming baby!

Why couldn't he go in there with them? It used to be great, he thought, jumping on their bed and using Gordon's knees to slide down. He liked snuggling between them in their warmth. Every Sunday morning it had been like that. "Having a good lie in," Dad called it.

Now, they said, he was too rough or too noisy when he went in there to play with his Dad. He might hurt the baby or disturb her.

"Huh!"

He quite liked being left on his own with Gwyn. He didn't mind being asked to look after her when Mam was busy. He enjoyed seeing her growing day-by-day. She was interesting because she was always doing something new. He was trying to persuade her to speak.

"Say Michael! Say Michael," he'd ask her and she'd laugh back at him and kick her legs at his coaxing. She liked it when Michael tickled her and shook her rattle for her.

One day, when he asked her to, "Say Michael!" she didn't just gurgle and smile back at him, she went, "Mmmm."

Michael left her lying on the blanket in front of the fire and ran into the kitchen. "Mam! Mam! She said it! She said my name!"

Michael was delirious with excitement and pleasure.

She was still a bit young for that to have really happened, thought Margaret, but she was pleased. She could see that Michael really loved his dark-haired little sister. For a time it had worried her that he was not at all keen on having a baby sister who took up so much of her energy.

Yes, there were times when Michael thought Gwyn was really brilliant. But not on Sunday mornings!

Still lying in his bed, in his own room, he reached for his nursery rhymes book. He looked at the pictures and tried reciting the ones Gordon had taught him. It was no use: he was feeling too sorry for himself. He threw the book down, pulled the bedclothes over his head and said to himself again, "It's not fair! Not fair!"

From the dark, where he was hidden under the clothes, unexpectedly, he heard his father's voice, "Where's Michael? I wonder where Michael is?"

Michael stayed under the bedclothes and kept very still. He even tried holding his breath. Dad said, "I know where he is, he's gone downstairs."

Michael pushed the bedclothes back "No, I haven't! I'm here Dad, I was hiding from you."

Already partly dressed, Gordon lay down on top of the bedclothes. Laughing, he said, "Move over, you're taking up all the room. Now come on, I want to hear your nursery rhymes. Right?" Michael nodded eagerly.

And that's how it was every Sunday morning after that. His father came in, stayed with Mike, chatted with him and helped him dress. Then they went downstairs together, lit the fire, washed in cold water and made a cup of tea. Michael didn't like tea so he had a drink of water. Gordon took a cuppa up to Margaret.

Then they had their porridge. Gordon ate his quickly and went outside to the lav. It was a double-seater, in the shed, in the yard, the one they shared with Next-door. Michael hated it in there because underneath the seat there was a deep hole and nasty smells came up. He was terrified of slipping down into that hole. He wished he could still be allowed to sit on his potty. It was all right for Gwyn. She didn't have to sit out there in the cold all by herself!

After he'd met his new friend Rob, he warned Michael, "Sometimes rats come up out of that hole. Mind they don't bite your bum!"

"You're only kidding me, aren't you Rob?"

"Suppose so," said Rob.

While Michael was carrying on eating his breakfast, he heard an angry voice outside. It was Next-door having a go at Gordon because, she said, Margaret wasn't keeping the wooden seat of the shared lav. clean enough. It wasn't true, because Mike had seen his mother scrubbing with carbolic soap and a stiff-bristled brush out there nearly every day. He didn't like the sickly smell of that carbolic.

"Well, just you tell your missus, it's time she mended her ways. All you young 'uns think on is lounging about, doing nowt, while us old'‘uns does all the work."

It went on like that until Gordon became fed up, left her to ramble on, and came in. He hadn't said much in reply. He wasn't one for trouble. Silent, in contemplation, he put the kettle on the fire again. He needed more hot water because he shaved straight after breakfast on Sundays. Michael loved to watch him, but he didn't like it when, sometimes, Gordon lifted him up and rubbed his unshaven cheeks against Michael's, really hard. It was just like sand-paper! Michael always screamed and Margaret would shout at his Dad from upstairs to stop it. So Gordon put him down.

When Margaret came for her breakfast and Gordon told her about Next-door, Margaret wasn't worried.

"Oh she's always at me! Best take no notice! She's a fine one to talk. Dresses like a scarecrow and smells like a drain! She's all on her own. Nothing else to think about!"

Labels:

Edward Street,

Lancaster,

Sunday Mornings

Saturday, 3 September 2011

Chapter 5: Edward Street

Michael's father was a strong man with muscular arms and hairy legs. He had dark hair, weather-beaten features, and the bluest eyes you ever saw. His wife's friend, flighty Joyce, the one he used to have it away with before he met Margaret, said he had the nicest eyes she'd ever seen in a man.

Gordon could be moody occasionally but he rarely lost his temper. His and Margaret's was a love-match. Sometimes, they disagreed and fell out, Margaret alway found it was difficult to have a real row with Gordon. She might rave, but he would go quiet and sulk. It excited both of them when they rowed, though. After it was over, they usually made love.

Gordon enjoyed sex but didn't get enough of it. Sometimes, when he felt particularly frustrated, he wondered why he'd married. He'd had more of it when he was single. But he kept these thoughts to himself...

Gordon had two alarm clocks by his bedside. The extra one was there in case the first one failed to ring. He dare not be late for work. To ensure being there in time, he had to set out at six every morning. It was a long walk. He carried his lunch box and a rubber cape and leggings, in case it rained. In all seasons, he wore a flat cap when he went to work, one with a check pattern on the top. He was a craftsman so he wore a tie.

It was nearly two miles to where he worked at Williamson's lino factory. Many still called it the Shipyard, although linoleum had been made there for donkey's years. Gordon's long stride meant that he overtook many other workers on his way. He used to set himself a target as he left home, of how many he would pass on his way to Williamson's. Sometimes, he ran the last few hundred yards in order to meet his arbitrary target.

"Why's he running?" a mate who saw him would think, "We're not late?"

Working days, Margaret was always first up, her footsteps light on the stairs. There was the scratching of a match and soon, crackling from the wood, under the coal on the fire. Gordon always laid it the night before. The next thing Michael heard was the sound of his Mam filling the kettle to boil hot-water. Margaret brewed the first cup of tea of the day and made a bowl of hot porridge, to send Gordon off warm to work.

Even at that early hour, you could hear the machinery, in the mill, behind their Edward Street house, humming away. Twice a day, that mill's buzzer would sound, a sort of siren, to warn the workers that they had better hurry or they'd be late. That would mean, without exception, a punishment: a docking of wages, for a few minutes lateness; or a sending home, for a day without pay. Worse still you might get the sack, especially if one of the bosses didn't like you.

Some still paid a knocker-upper to bang on their bedroom windows with his long pole, to make sure they got out of bed promptly. He was a legacy from, not that long previously, when few had watches or clocks or could not tell the time. When Gordon hurt an ankle, playing football,for the works team, he worried even more about being late. He left the house half an hour earlier, every morning, because he could only limp there slowly. He kept that up for six weeks, in agony every day. Thankfully, the ankle mended. But he packed in playing soccer. He couldn't afford to have time-off, if he was injured. It was the same if he felt ill: somehow, he always struggled into work.

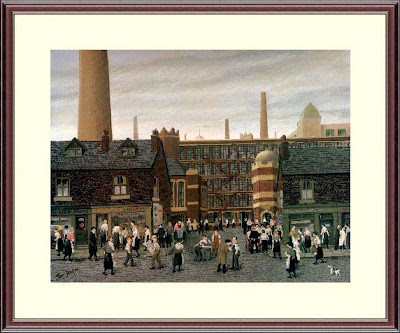

The buzer for afternoon work, in the mill up Moor Lane, fascinated the infant Michael. When he heard it, he'd persuade his mother to open the parlour door of their two-up and two-down house. She'd put one of their bent-wood chairs up against the window. She'd place a cushion on the chair and lift Michael on to it. He'd kneel there and watch what happened in the street.

As if by magic, people appeared outside and passed the window. They looked like Lowry's matchstick people. Nearly all wore dark clothing. They shuffled past and headed round the corner of Moor Lane. Some were wearing clogs, which clattered on the pavement, and a young lad would occasionally kick the cobbles of the road and make sparks fly, as the metal on the soles of his clogs smacked against the stones. Latecomers hurried past and finally, there was the odd scampering boy, his face anxious, determined not to be late, for fear of losing precious pence.

After the last one had gone, Mike would call to his mother to lift him down. He had power over her, exercised it mercilessly and she didn't seem to mind. His slightest wish, his every whim was catered for by his Mam. She had to jump to it or he'd moan at her or cry! Gordon thought that she pampered him too much.